Introduction

The health care system in the United States continues to experience skyrocketing costs, high chronic disease burden, and poor population health. It has repeatedly fallen short on delivering timely and accessible health care, and disparities between populations continue to grow — as the COVID-19 crisis has highlighted. In particular, inadequate access to primary health care has diminished the U.S. system’s capacity to prevent chronic disease and manage population health, led to delayed diagnoses and incomplete treatment adherence, and created problems related to patient safety and care coordination.1

With public frustration over the current system mounting, many in the United States believe that significant reforms are warranted. Costa Rica offers an example of an efficient health care system centered around a backbone of robust, community-oriented primary health care, characterized by strong and effective use of community health workers to improve access, quality, and equity. Although circumstances in Costa Rica and the U.S. differ in many ways, the story of this Latin American nation’s success demonstrates what can be achieved with other models of care.

Primary Health Care in Costa Rica: How it Works

Costa Rica’s community-oriented primary health care (PHC) model is built on five main pillars:

- Integration of public health with primary health care: Responsibility for the provision of all curative and preventive public health care — from public health functions to primary, secondary, and tertiary care — is consolidated under one agency, the Social Security Agency (Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social, or CCSS). The Ministry of Health sets policy and national direction but is not a direct provider of care. This integration promotes efficiency and reduces redundancy. In the U.S., such consolidation would be equivalent to the Department of Health and Human Services’ provision of oversight and national direction to the Department of Veterans Affairs, except extended to the entire population.

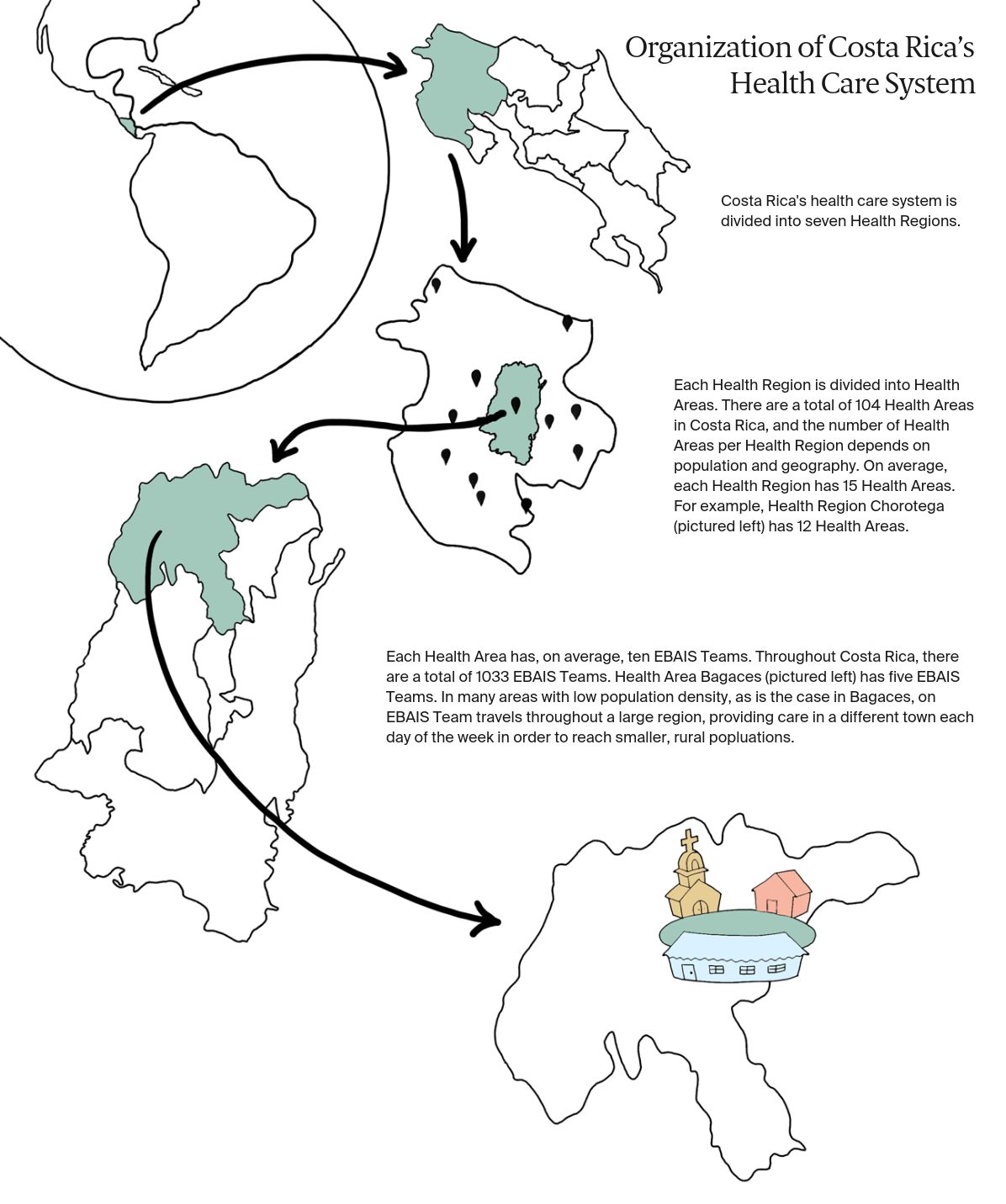

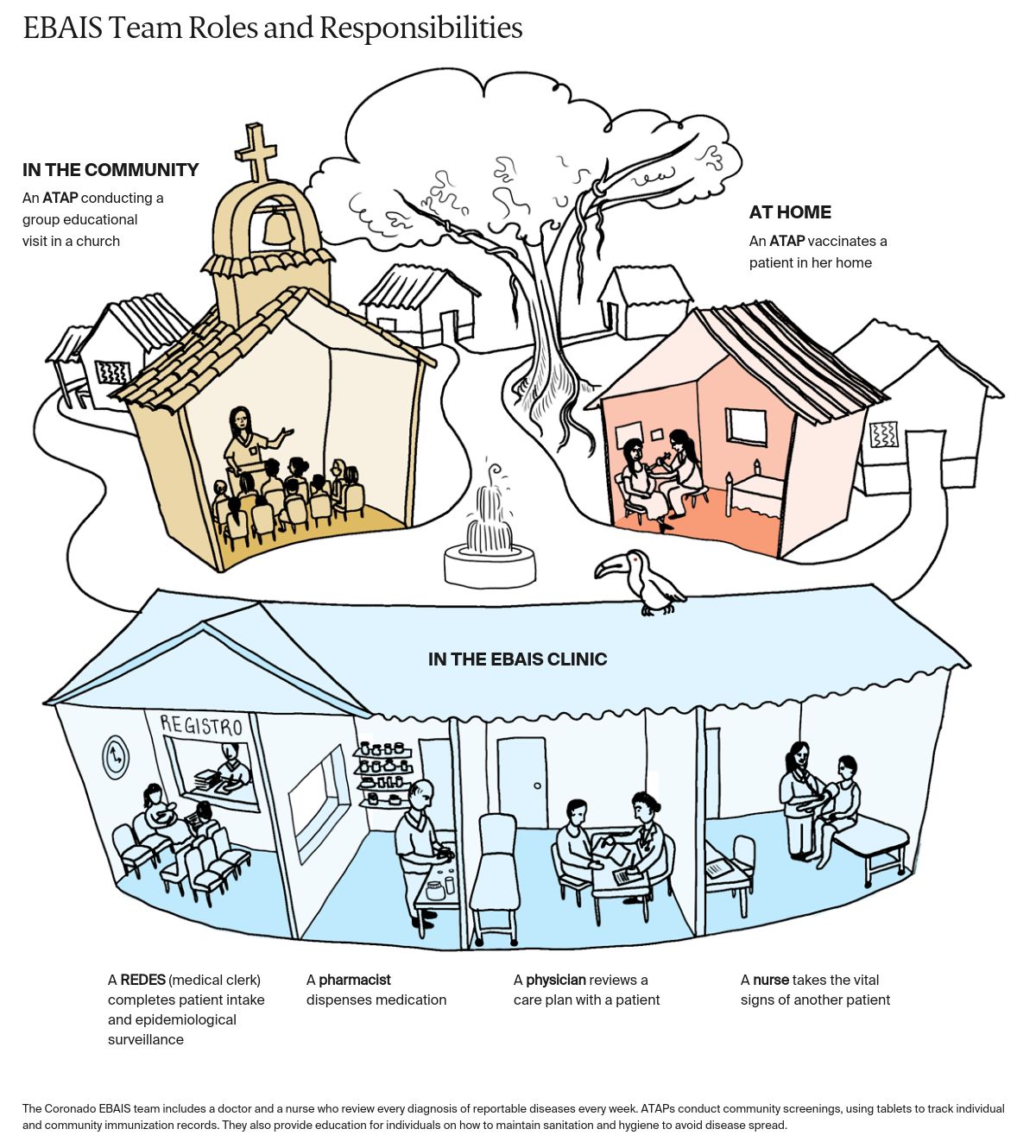

- Multidisciplinary teams integrated within the community: Each integrated PHC team, known as an equipo básico de atención integral de salud (or EBAIS), provides comprehensive and coordinated PHC. Teams comprise a doctor, nurse assistant, medical clerk, and asistente técnico en atención primaria (ATAP). ATAPs, similar to advanced community health workers, aim to visit each household annually, using risk stratification to prioritize order and frequency of home visits (see box). Additional support for EBAIS is provided by teams of nutritionists, psychiatrists, and pharmacists within the main PHC organizational unit, called a health area. Each health area provides care to 30,000 to 110,000 residents at five to 15 EBAIS clinics (Exhibit 1).

- Geographic empanelment: All citizens are assigned to an EBAIS team through geographic empanelment, which promotes access and continuity of care. Each team has a target panel size of about 4,000 people. To promote greater equity in access and outcomes, empanelment and introduction of EBAIS teams began in the country’s most medically underserved rural areas, and then moved to urban areas, including the capital, San José.

- Measurement and quality improvement at all levels: Quality assurance and improvement are a primary focus for PHC and the health system overall and are supported by robust data feedback mechanisms. EBAIS teams collect comprehensive population data, which are compiled by the health area and sent to the national level of the CCSS. The data are used to assess performance against targets and ensure a high quality of care.

- Integration of digital technologies at all levels: The country’s electronic health record (EHR) system, the expediente digital único en salud, facilitates the delivery of comprehensive care to patients. Patient charts function as clinical guides, reminding providers of issues to discuss during their visit, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and elder care. EBAIS teams use mobile tablets for data collection across urban and rural settings.