In 2018, Ohio released a report that estimated its Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) were losing substantial funds because of spread-pricing arrangements.6 In response, the state passed legislation requiring pass-through pricing contracts between PBMs and Medicaid MCOs. Other states, including Pennsylvania and New York, have examined the issue of spread pricing in their MCOs and its impact on reimbursement rates for generic drugs to pharmacies.

While plan sponsors have the choice between spread pricing and pass-through contracts, there are no public data on which type of contract offers lower-cost options to employers. The proprietary nature of PBM–plan sponsor contracts and PBM–pharmacy contracts makes it difficult to study the impact of spread vs. pass-through contracts on generic reimbursement and overall pharmaceutical spending.

More information is needed to determine whether pass-through or spread-pricing contracts offer greater savings to plan sponsors and ultimately patients. Armed with this information, policymakers would be in a better position to determine whether policies should limit the use of spread pricing.

Which Distribution Channel Leads to the Lowest Costs?

To understand which pharmacy distribution channels offer the lowest costs, studies have compared the price of prescription drugs across mail-order and brick-and-mortar pharmacies. On average, retail pharmacies provide lower generic drug costs than do mail-order pharmacies and higher rates of generic substitution.7 Conversely, the cost of brand-name drugs is slightly higher at brick-and-mortar vs. mail-order pharmacies.8 However, studies have not assessed differences in total reimbursement across brick-and-mortar and mail-order pharmacies, including both MAC schedules and GERs, making it difficult to determine which are more cost-efficient.

Drug formularies that steer patients toward mail-order prescription drugs have been criticized because some PBMs own the mail-order pharmacies and therefore profit from the increased business. Under federal law, Medicare Part D plans are not allowed to use financial incentives such as lower copayments to drive mail-order use. By contrast, such financial incentives are allowed in the commercial market and roughly half of employers report that their plans have such incentives. This suggests that PBMs are pushing patients toward their mail-order subsidiaries. With mail-order pharmacies accounting for more than one-third of retail pharmacy sales, it is important that future research assess the full reimbursement picture to better understand the impact that this distribution channel has on pharmaceutical spending.

Can Greater Cost Transparency Stimulate Price Competition?

Lack of transparency throughout the drug distribution system is a major challenge, but new innovations can increase transparency. In November 2020, Amazon launched Amazon Pharmacy. Under this model, patients purchase their prescription medications online via an Amazon portal in which they can see the price of their medication with and without insurance.

Giving patients the ability to observe the difference between a drug’s retail list price and the insurer’s negotiated price may bring transparency to the retail pharmacy market and drive competition. The concept is similar to GoodRx, an online company that partners with PBMs to show customers the lowest-cost prescription drug option net of negotiated discounts.9 Through a partnership between Amazon and Insider Rx (a subsidiary of ExpressScripts), Amazon Prime users also may receive discounts of up to 80 percent on generic drugs and 40 percent on brand-name drugs.10 Price transparency and such discounts position Amazon to compete with mass merchant and supermarket pharmacies. It also may increase price competition in the mail-order pharmacy industry.11

Under a federal rule passed in November 2020, commercial health insurers will be required, starting in 2022, to publish pharmaceutical prices they negotiate with PBMs and drug manufacturers.12 These “allowable costs” are reflected in the PBM plan contracts through MAC schedules and GERs for generics and through specified percentage discounts off the average wholesale price for brand-name drugs. If the rule survives legal challenges, making these rates public may help plan sponsors ensure they are receiving the best prices available to other health plans and employers. Even under this rule, however, there is no transparency requirement for PBMs’ actual pharmacy reimbursement levels. If PBM–pharmacy MAC schedules, GERs, and branded drug reimbursement rates were also publicly available, plan sponsors and patients would be able to ensure they are purchasing drugs at the lowest prices across pharmacy types.

How Can We Protect Independent Pharmacies in Underserved Markets?

Historically, independent pharmacies have derived much of their revenue from generic drugs. However, decreasing reimbursement rates and increased competition among pharmacies have resulted in shrinking profit margins. It is therefore important to devise a reimbursement system that supports independent pharmacies in areas dependent on their services to ensure equitable access to prescription drugs.

One such change to the reimbursement system could include discontinuing use of direct and indirect remuneration (DIR) fees for Medicare Part D beneficiaries. DIR fees are payments that pharmacies return to health plans if they do not meet specified performance goals related to adherence, gaps in care, or missing prescriptions. In a survey of independent pharmacists, 63 percent reported DIR fees as the largest challenge they face.13 DIR fees also have been criticized on the grounds that they are not credited back to Medicare beneficiaries at the point of sale, resulting in higher out-of-pocket drug costs.14 Federal and state legislation has been proposed to help pharmacists and patients by requiring greater transparency around DIR fees or eliminating them altogether.

Can Pharmacists Play an Expanded Role in Preventive and Chronic Health Care?

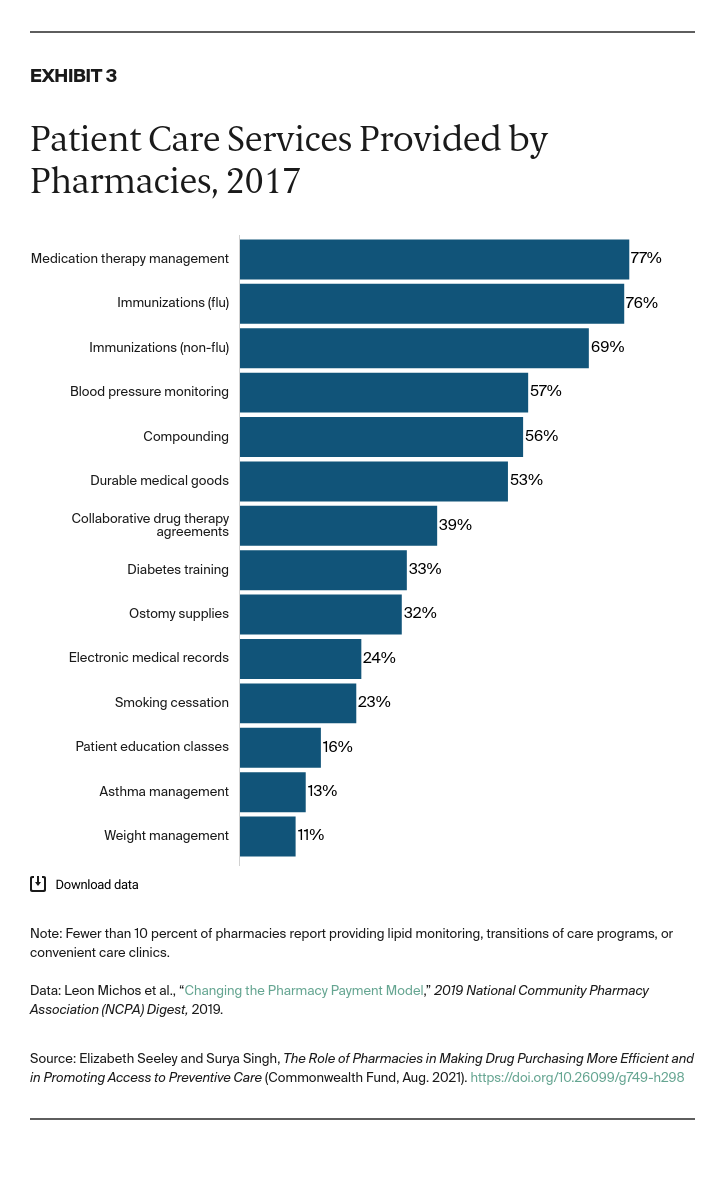

Another way to help independent pharmacies and increase delivery of preventive services would be to support pharmacists taking on greater roles in providing billable health care services. Pharmacies are engaging in an increasing array of services, including drug adherence programs, value-based pharmacy networks, the dispensing of specialty drugs, e-commerce platforms, and home delivery, all of which can increase medication adherence and therefore the value of drugs. (See box below for a more in-depth discussion on pharmacies’ roles in quality improvement and value-based reimbursement.)

Pharmacies are also key to our public health infrastructure. For example, as shown in Exhibit 3, most independent and major chain pharmacies provide immunizations,15 with pharmacies currently playing a vital role in the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. More than half (57%) of independent pharmacies also monitor blood pressure.