Abstract

- Issue: For Medicare beneficiaries, the COVID-19 pandemic has made the management of chronic conditions more challenging. Several policy options may help ensure that these individuals can maintain their health during the pandemic.

- Goals: Summarize the impact of COVID-19 on Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions, outline the existing policy response, and provide options for future policies to protect this population.

- Methods: Review of the literature on the impact of COVID-19 on people with chronic conditions as well as a review of policies from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

- Key Findings: Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions are at high risk for having essential health services disrupted by the pandemic. Many of these individuals have already experienced substantial disruptions to disease management and reduced access to necessary care.

- Conclusion: CMS has implemented policies to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on beneficiaries with chronic conditions. CMS waivers have expanded telemedicine services and shifted more services toward outpatient and home-based care settings. Options that continue and expand current policies may help ensure continued timely access to care for this population.

Introduction

As of March 2021, the United States has a higher number of COVID-19 cases and deaths than any other country in the world. In the first 11 months of 2020, more than 1.9 million Medicare beneficiaries were infected with COVID-19, and more than 490,000 were hospitalized.1 Given the high chronic disease burden in the U.S., a large share of the Medicare population is living with chronic conditions.2 In March 2020, 89 percent of adults hospitalized for COVID-19 had preexisting conditions.3 The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced additional challenges for these individuals; not only are they at a heightened risk for contracting the virus and experiencing severe illness, but they are also more likely to have had vital health services interrupted by the pandemic.

In the coming months, there is an opportunity to reenvision care delivery models and develop policies and practices that protect Medicare beneficiaries living with chronic conditions. In this brief, we:

- Summarize the ways in which the coronavirus pandemic has affected Medicare beneficiaries living with chronic conditions, both directly through the risk of severe illness and indirectly through the disruption of care.

- Outline the policies that have been implemented thus far to protect this population.

- Identify additional policy options, including telemedicine and hospital-at-home programs, that may allow Medicare beneficiaries living with chronic conditions to more easily manage their diseases and access care during the pandemic.

Findings

Chronic Conditions and COVID-19 in the Medicare Population

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, individuals living with certain chronic conditions, such as chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, are at an increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19. Other chronic conditions, such as hypertension, liver disease, and type 1 diabetes, may increase the risk of severe COVID-19, although the evidence for these conditions is less clear. Estimates suggest that about 45.4 percent of U.S. adults might have a higher risk for COVID-19 complications because of chronic conditions.4

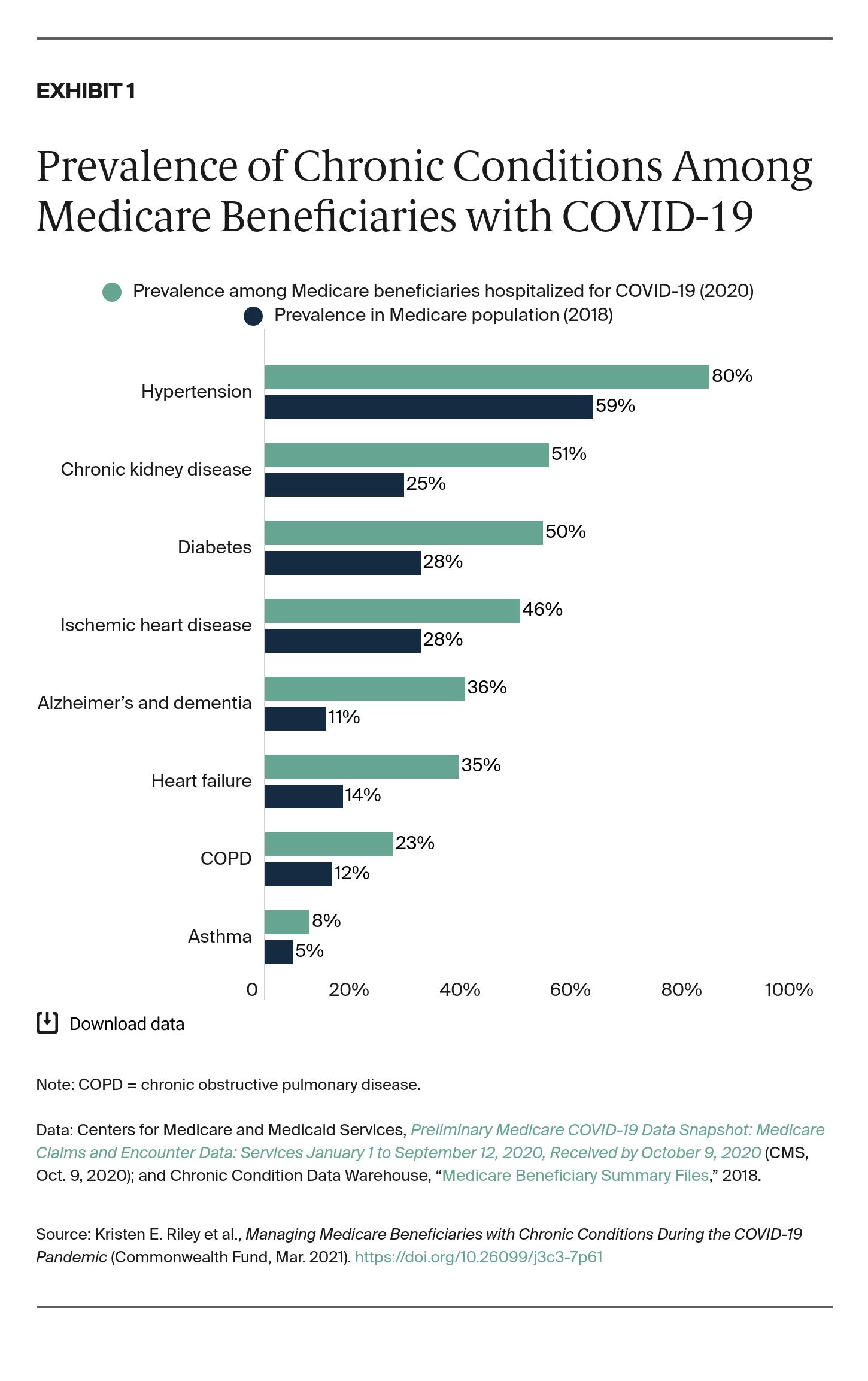

Chronic conditions are common among the Medicare population, with a significant share living with at least one chronic disease (Exhibit 1).5 Of all non-dual-eligible Medicare beneficiaries in 2017, 66 percent were living with two or more chronic conditions.6 Individuals with multiple chronic conditions are at an even higher risk for experiencing severe illness from COVID-19 while living with the burden of managing multiple chronic illnesses at once.

Given that COVID-19 disproportionately impacts those living with chronic conditions and individuals over age 65, the Medicare population is affected by multiple risk factors for the disease. Of the fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for COVID-19, a high proportion are living with chronic conditions (Exhibit 1).7 These impacts are further heightened in certain subgroups of the Medicare population, such as dual-eligible beneficiaries, who were hospitalized for COVID-19 at more than four times the rate of Medicare-only beneficiaries.8

Challenges to Managing Chronic Conditions During COVID-19

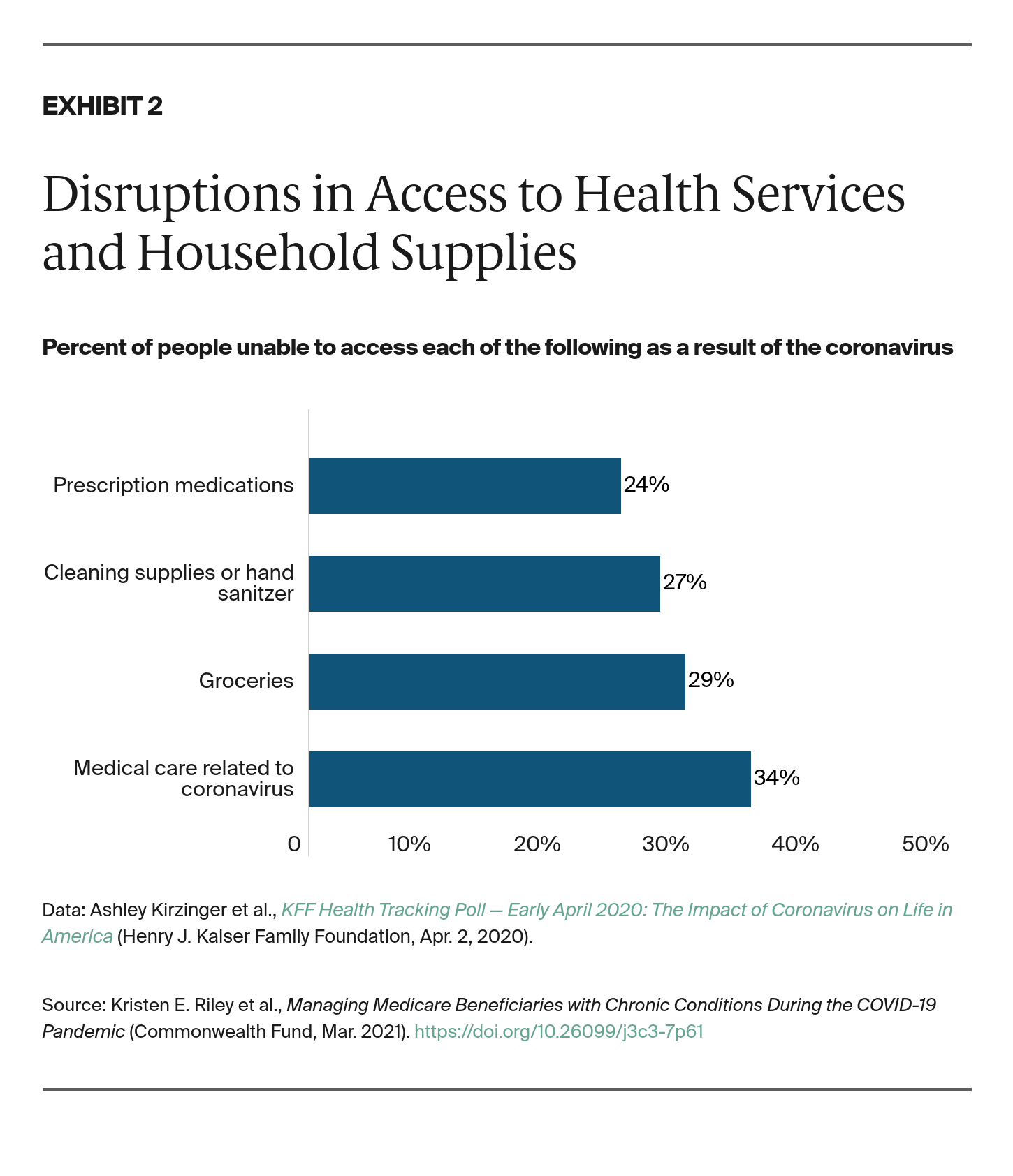

Disruptions in routine care. Infectious disease outbreaks present significant challenges to the management of chronic conditions. They can delay elective procedures, prevent patients from seeking both regular and emergent care, and even present barriers to obtaining prescriptions. These disruptions in care have affected the U.S. population, with one-third of adults unable to get medical care unrelated to the coronavirus in March 2020 (Exhibit 2).9 By the end of June 2020, four in 10 U.S. adults reported delaying or avoiding medical care because of the pandemic.10

These challenges are amplified for individuals living with chronic conditions, as this group is more likely to need regular medical care and prescriptions. In June 2020, about 55 percent of adults living with multiple chronic conditions reported delays or avoidance of medical care attributable to the pandemic.11 In another survey of U.S. patients, 69 percent reported that COVID-19 has affected their ability to manage their chronic conditions.12 In April 2020, 42 percent of those living with chronic conditions were worried or very worried about going to the doctor’s office or hospital during the pandemic, with an additional 10 percent citing that they were so worried they would avoid necessary care.13

Disruptions in emergent care. Not only are patients living with chronic conditions less able to receive routine medical care, but they are also less likely to seek care in emergent situations. Emergency department volume dropped by about half from March 2020 to April 2020 in one community hospital in California.14 These reductions persisted throughout the spring; in the 10 weeks following the national emergency declaration in March, emergency department visits for heart attack, stroke, and hyperglycemic crisis all declined nationally.15

Existing Policy Responses

The expansion of telemedicine services. One solution to mitigating disruptions in care for Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions is to scale up telemedicine services, which have been shown to improve health outcomes for chronic care.16 Telemedicine allows providers to see patients while also reducing the risk of COVID-19 exposure.

In the last week of March 2020, telemedicine visits increased by 154 percent, compared with the same period in 2019.17 Telemedicine use increased by 13,000 percent among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries between March 2020 and April 2020. Dual-eligible beneficiaries exhibited higher rates of telemedicine use (34%) compared with Medicare-only beneficiaries (26%), suggesting that the expansion of telemedicine may have made care more accessible for low-income individuals.18 Beyond preventing COVID-19 exposure, telemedicine reduces barriers to care such as transportation, preserves personal protective equipment and other supplies, and allows facilities to maintain social distancing protocols.

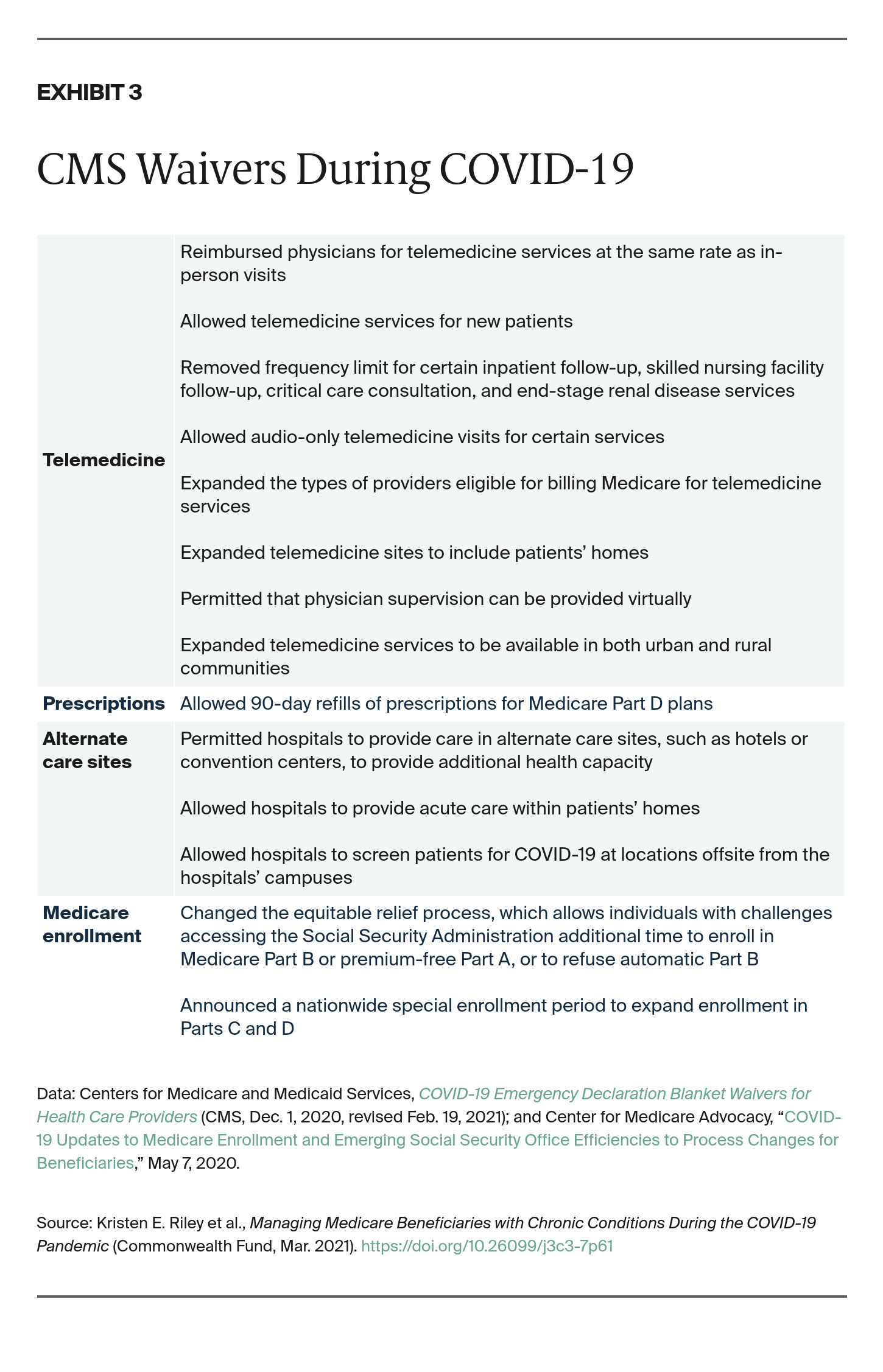

Early on in the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented policies to make telemedicine services more accessible and incentivize utilization of these services (Exhibit 3).19 In March 2020, these policies increased the financial incentives for providing telemedicine services, including paying physicians for telemedicine services at the same rate as in-person services and reimbursing physicians for both audio and video visits. CMS also implemented policies allowing providers to see new patients through telemedicine. At the end of April 2020, CMS further relaxed telemedicine restrictions by increasing payments for audio-only visits and expanding the list of covered providers.

Ensuring access to care. Beyond the expansion of telemedicine, other policies have improved access to care during COVID-19. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, for example, required that Medicare Part D plans provide up to 90-day refills of prescriptions, allowing beneficiaries enrolled in Part D to access an extended supply of medications and avoid traveling to the pharmacy as frequently.20

Moreover, CMS’s Hospital Without Walls initiative expanded access to care by allowing hospitals to provide health services outside of their existing walls and develop dedicated COVID-19 spaces. The Acute Hospital Care at Home program goes one step further by permitting care within patients’ homes. This program allows individuals with chronic conditions to seek acute care outside of the hospital and access necessary care while also reducing the risk of infection.21

Looking Ahead: Persistent Challenges

While the recent decline in cases and rapid vaccination rollout provide cautious optimism that we are at the beginning of the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions may continue to face barriers to disease management. Even before the pandemic, U.S. hospitals were often running near full capacity, and it is unknown how rapidly the health system may be able to meet the pent-up demand for medical and surgical care.22 Delays in care also may have long-term detrimental impacts on the health of these patients and the health system more broadly. Experience from prior pandemics, such as the 2003 SARS outbreak, suggests that hospitalizations for certain chronic conditions may plummet during the pandemic, only to surge afterward.23

For chronic conditions such as heart disease and diabetes, regular medical care helps prevent emergent situations. The cancellation of routine visits may ultimately result in more acute care needs. When the COVID-19 pandemic comes under control, high demand for provider visits may create backlogs in accessing care, adding more stress to an overburdened health system.

The Secondary Impacts on Chronic Condition Management

Not only has the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the management of chronic conditions through the impacts outlined above, but it also has presented a series of secondary consequences. For those living with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and heart disease, exercise is critical to disease management. As gyms closed their doors and public health officials urged individuals to stay home during the months of March and April 2020, physical activity declined by 48 percent.24

The pandemic also has presented challenges to accessing groceries and fresh produce (Exhibit 2).25 This may lead to a less healthy diet which, like exercise, is a critical component in managing many chronic conditions.

Finally, the isolation that many have faced during the pandemic can be detrimental to mental health, particularly for older adults and those living with chronic conditions. Eighty percent of health care professionals in one survey reported that the mental health of their patients with chronic disease worsened during the pandemic.26 Moreover, many older adults have experienced heightened loneliness and isolation because of COVID-19, with one survey finding that about half of older adults reported feeling more isolated in June 2020 than they had before the pandemic.27

Policy Options

With uncertainty about how the long the COVID-19 pandemic will last, it is important to protect those living with chronic conditions and prevent further care disruptions. Targeted policies can help mitigate both the direct and indirect consequences of disrupted care during COVID-19. Telemedicine is a promising alternative to in-person visits that keeps individuals living with chronic conditions safe while simultaneously allowing them to receive necessary care. Despite the remarkable progress CMS and providers have made in increasing the accessibility of these services, barriers remain.28

Ensure Equitable Adoption of Telemedicine

An important policy consideration will be to ensure that any telemedicine solution does not exacerbate the immense health disparities exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Older adults, who make up the majority of Medicare beneficiaries, may not have the digital literacy or technology to easily navigate telemedicine services. One survey from 2015, for example, found that more than one-third of U.S. households headed by a person age 65 or older did not have a desktop or laptop, and more than half did not have a smartphone.29

The COVID-19 pandemic also has affected certain racial and ethnic groups disproportionately, with Black, Latinx, and American Indian populations more than four times as likely to be hospitalized for the virus as white populations.30 These groups are also more likely to have low socioeconomic status and less access to digital technologies.31 One analysis found that U.S. adults who are not digitally literate were more likely to be older and Black or Latinx, suggesting that Medicare beneficiaries from minority communities are especially at risk for falling below the digital divide.32

Telemedicine runs the risk of excluding these populations and leaving them to manage their chronic conditions without adequate support.33 One option is to expand telemedicine to specifically address the challenges faced by Medicare beneficiaries, particularly those from minority communities. One provider initiative that could address gaps in digital literacy among older adults from minority communities is conducting “practice visits,” during which administrative staff conduct mock telemedicine visits to ensure patients can navigate technological tools.34

Providers also could scale up digital technologies in lower-resourced health centers and low-income communities where the incidence of COVID-19 is particularly high. Some primary care organizations have already distributed technological platforms, like tablets, to patients to support telemedicine.35 By expanding programs that address gaps in digital literacy and improving access to digital tools and technologies, we can help ensure that the shift toward telemedicine does not exacerbate existing health disparities.

Accelerate the Transition to Outpatient and Home-Based Care

In response to the critical shortage of inpatient beds during the COVID-19 pandemic, CMS advanced the Hospital Without Walls initiative, a series of waivers that have allowed acute care to be delivered outside of hospitals. These waivers have allowed ambulatory surgical centers to become temporarily certified as hospitals to provide postoperative recovery for patients closer to home.

CMS also has announced the Acute Hospital Care at Home program, which will expand upon the Hospital Without Walls initiative and allow for certain services to be provided within a patient’s home. In randomized trials, this model has been shown to reduce costs, health care use, and readmissions while increasing physical capacity, compared with usual hospital care for patients with complex medical conditions.36 The outcomes of these new initiatives will likely provide critical guidance for the future.

Continue Regulatory Flexibility

In the future, continued regulatory flexibility and extension of CMS waivers could help improve chronic condition management in the Medicare population. Although Congress has instituted many regulatory changes to improve access to care during COVID-19, the vast majority of these policies are temporary and set to expire.37 CMS has stated that it will likely remove these policies gradually as the pandemic comes to an end. Yet at the same time, some policymakers have discussed permanently implementing certain popular policies, such as expanded reimbursements for telemedicine.

Because there will likely be a surge in demand for health care services as the virus abates, ensuring continued regulatory flexibility may be especially valuable. As we reconsider our health care system in the wake of COVID-19, we have the option to evaluate whether these policies and waivers can positively affect patients, providers, and the health system as a whole and, if so, consider making more permanent changes.

Conclusion

Medicare beneficiaries living with chronic conditions face multiple risks during COVID-19. They are at an increased risk for contracting the virus, experiencing disruptions in routine disease management, and being unable to access care through telemedicine. Policy options to mitigate these impacts include ensuring equity in the scale-up of telemedicine services, evaluating the outcomes of new outpatient and home-based care programs, and continuing regulatory flexibility.

While the pandemic has had profound consequences, it also has created the opportunity to reimagine the U.S. health care system to refine value around investments in patient-centered care. This includes moving away from the inpatient-dominant view of medical care and expanding acute care through telemedicine, ambulatory settings, and in-home settings.