Abstract

- Issue: Diabetes has a well-documented association with race and socioeconomic status; for example, the condition’s prevalence is significantly higher in Black versus white communities. This disparity may be exacerbated by treatment disparities, including differences in use of diabetes medications introduced since 2005.

- Goals: Examine trends and disparities in use of and expenditures for three new classes of diabetes drugs (glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors) by race, ethnicity, insurance coverage, education, and income.

- Methods: Analysis of Medical Expenditure Survey (MEPS) data from 2003 to 2019.

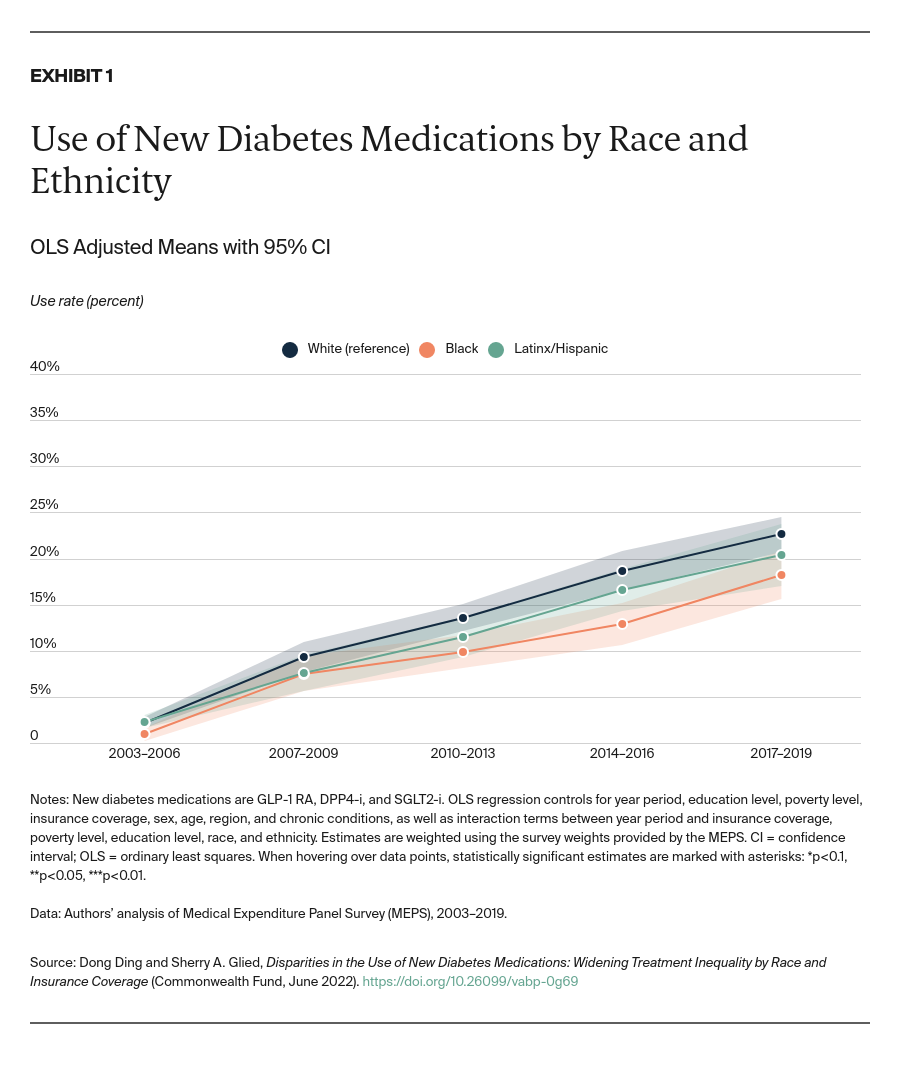

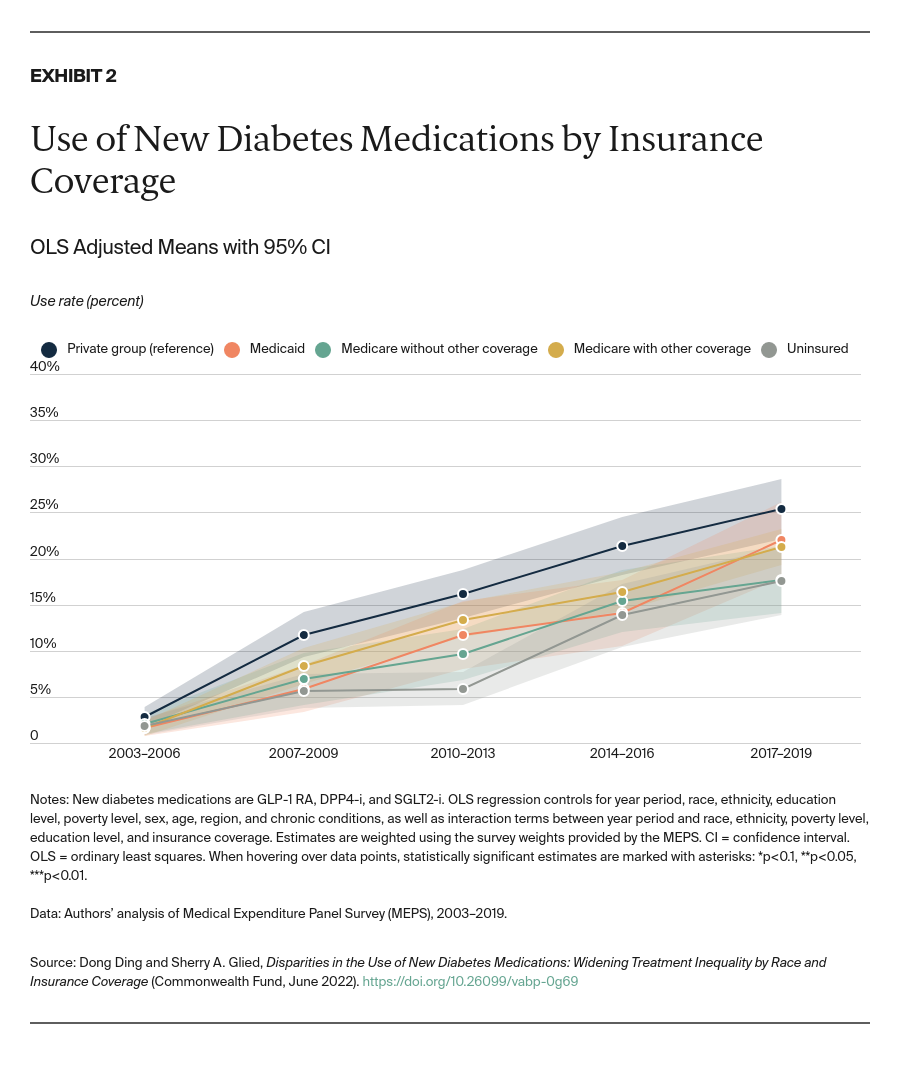

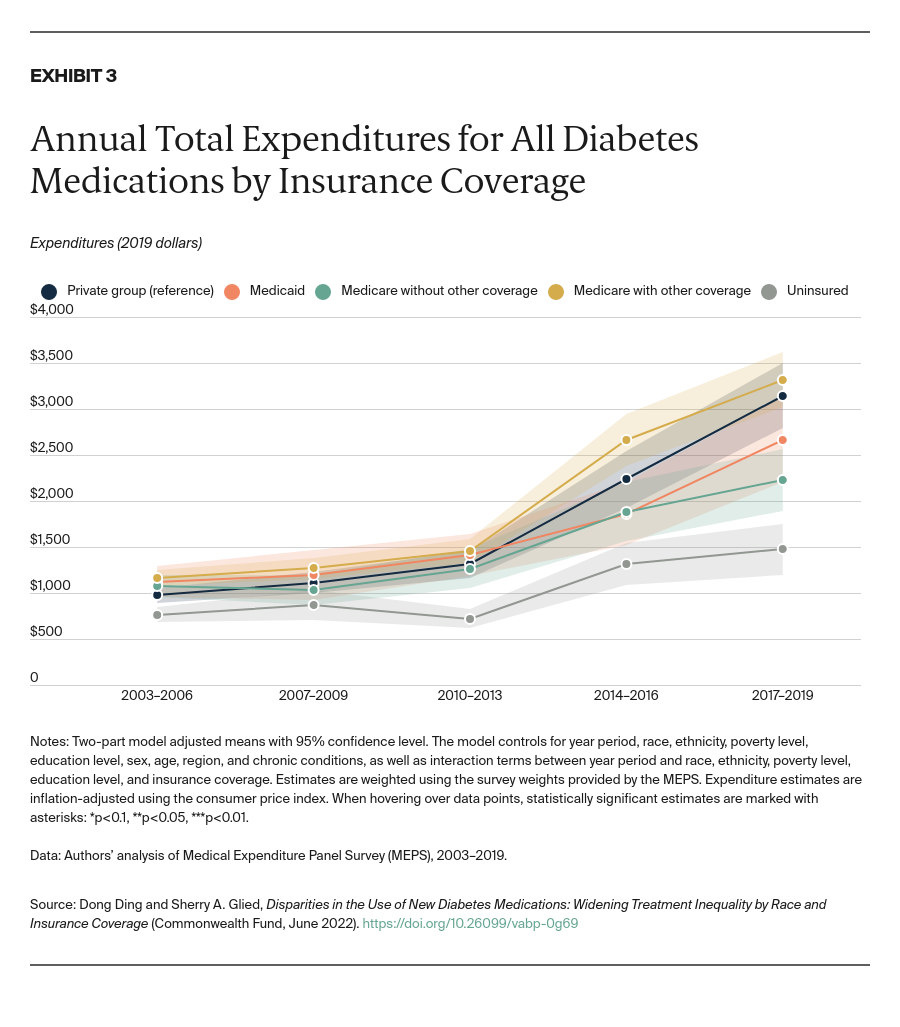

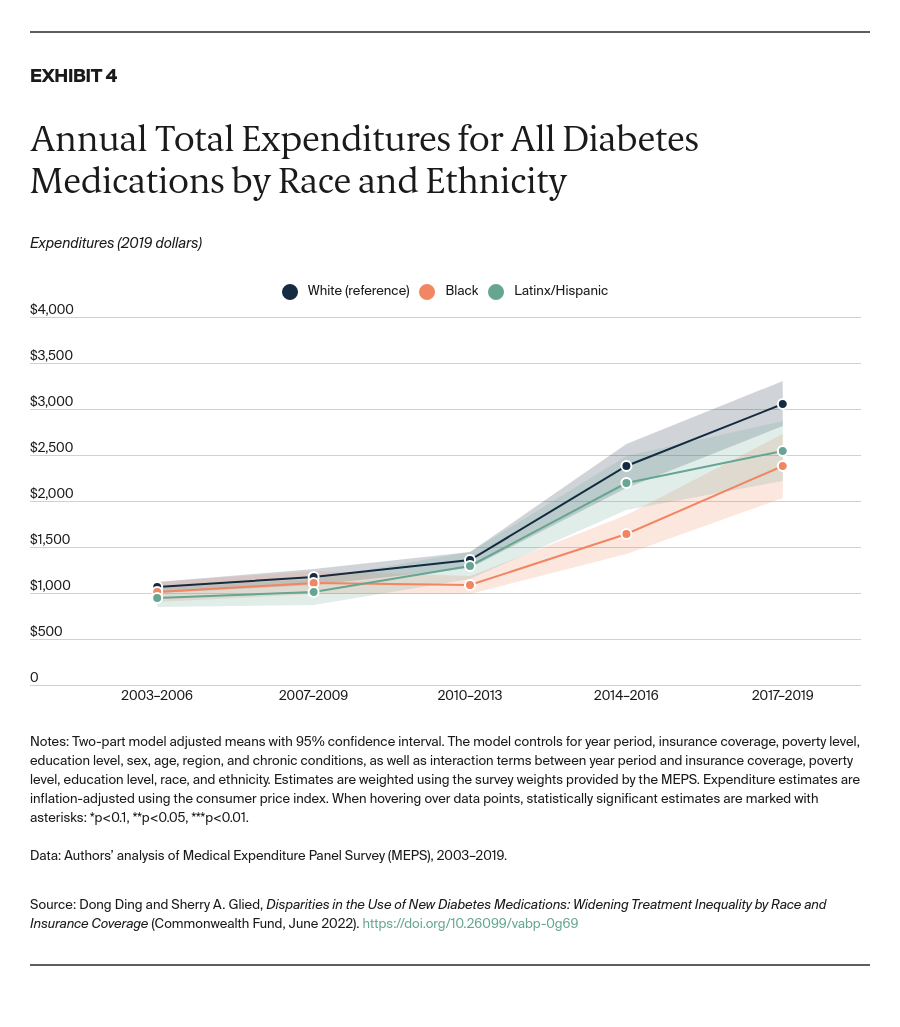

- Key Findings: Disparities in use between Black and white adults emerged soon after the drugs’ introduction, controlling for trends by insurance status, income, and education. These disparities widened significantly through 2019. Drug usage rates for Latinx/Hispanic people fall midway between rates for white and Black people. Similar disparities by insurance coverage also emerged shortly after the drugs became available and continue today. In addition, lower socioeconomic status has been independently associated with lower take-up of new medications. Disparities in spending are small in magnitude but increasing as use of these drugs grows.

- Conclusions: Efforts to narrow disparities in diabetes outcomes should account for the impact of disparate access to advances in diabetes treatment.

Introduction

Substantial and persistent disparities in health outcomes exist among people with diabetes by race, ethnicity, income, occupation, and other measures of socioeconomic status.1 These disparities are of particular concern because diabetes is one of the most common chronic conditions in the United States, affecting 13.4 percent of the adult population.2

Most research on disparities in diabetes has focused on the impact of underlying social determinants of health, such as food and housing, which affect the incidence of diabetes.3 But income, race, ethnicity, and other measures of socioeconomic status also affect outcomes among those who have been diagnosed with the condition. These outcome disparities may arise, in part, because of differences in access to effective diabetes treatment. Studies focused on access to effective diabetes treatments have demonstrated that provider- and organization-level interventions can generate outcome improvements through consistent follow-up, better communication with patients (including through community health workers), care coordination, and similar practices.4

The challenge of reducing disparities is, however, ongoing and dynamic. The introduction of new technologies and treatments is often linked to increasing disparities.5 Therefore, innovations in diabetes treatment, including the introduction of new pharmaceutical therapies that offer better or easier glycemic control or reduce the sequelae of diabetes, could exacerbate inequalities. The association between new treatments and disparities can arise because of a lack of financial access to new, more costly therapies.6 However, disparities in the use of new treatments, particularly by education status, are also found in countries with few financial barriers to access.7

Between the discovery of insulin in the early 1920s and the mid-1990s, there were few advances in pharmacological treatment of diabetes. In the past 25 years, however, nine new drug classes for diabetes treatment have been introduced.8 Three of these classes, introduced since 2005, demonstrate high efficacy and fewer side effects, particularly for type 2 diabetes:9 glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA); dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors (DPP4-i); and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2-i).

These drugs remain on patent and have high retail prices.10 In addition, drug companies now offer new combinations of agents in fixed doses; these formulations make adherence to therapy easier.11 Use of these new drugs has increased rapidly since their approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).12 However, prior research has shown racial and ethnic disparities in the use of these drugs, after controlling for people’s income and health insurance.13 Appendix Exhibit 1 describes overall trends in the use of drugs for diabetes control.

Recent policy action around diabetes care has focused on the cost of insulin. In this issue brief, we turn attention to three new classes of drugs used in the care of people with diabetes. Using 2003–2019 data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), we examine whether treatment disparities are widening contemporaneously with the introduction of new diabetes medications. (See “How We Conducted This Study” for further detail.)