Abstract

- Issue: A public option is a government-established health insurance plan designed to inject more competition into the market and improve coverage affordability over time. Despite widespread support, little progress has been made at the federal or state level toward creating such a plan. We propose a public option plan for California, Golden Choice, that would be based on the state’s “delegated model” of health care under which provider organizations accept the financial risk for delivering health care services.

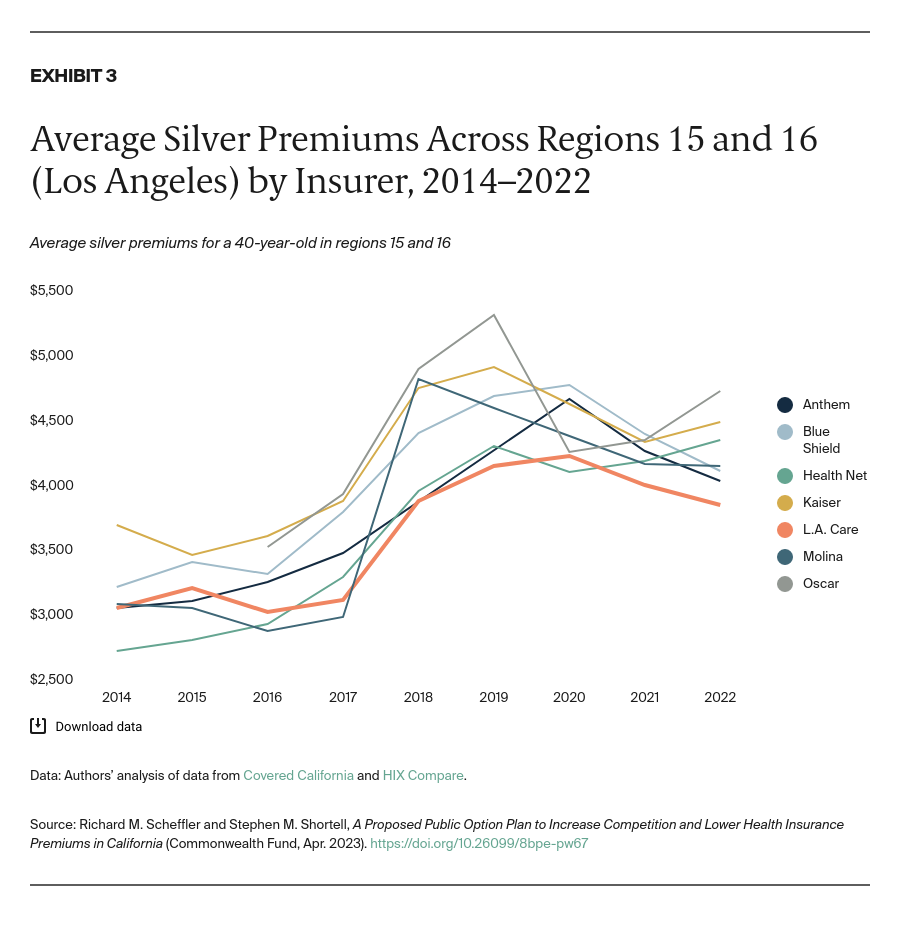

- Goals: To assess the proposed plan’s competitive impact on premiums in 19 markets in the Covered California health insurance marketplace.

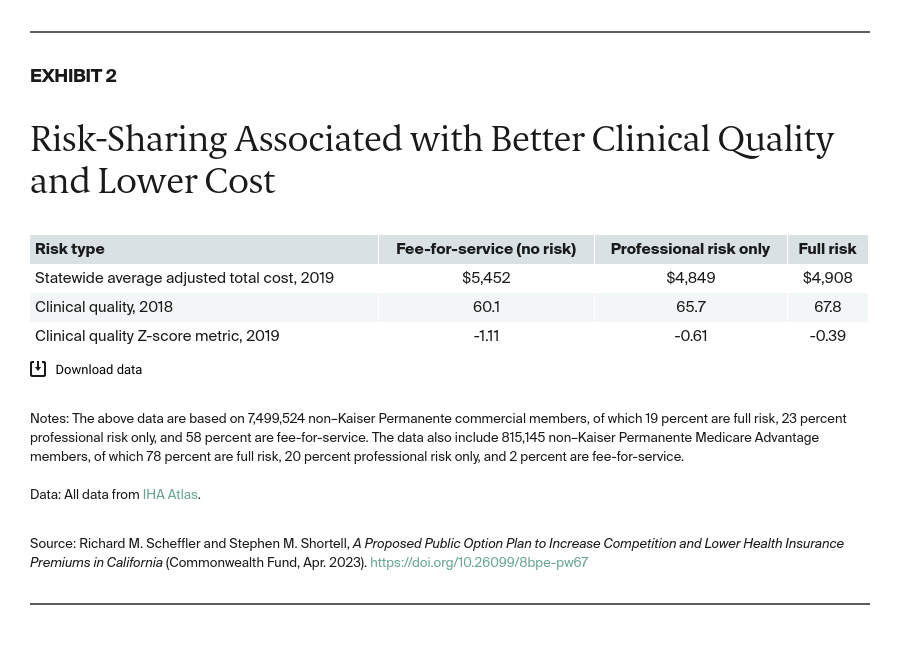

- Methods: Regression models using Integrated Healthcare Association and related data to estimate premiums; qualitative interviews with health plan and medical group leaders.

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Golden Choice would have the lowest premiums in 14 of the 19 Covered California regions and save $243 million ($1,389 per year per projected enrollee) in one year. Similar results were found when assessing the impact of public-employee HMOs as well as L.A. Care, the only county-based public option. Plan and medical group leaders reported that under Golden Choice, they could provide high-quality care while operating with premiums of 5 percent to 10 percent less than current plans. Moreover, a successful public option based on the delegated risk model would not require regulatory changes or mandates.

Introduction

Even though a “public option” health plan has support from the Biden administration as well as the majority of voters, little progress has been made in creating one at the federal level.1 At the state and county levels, public options — simply, health insurance plans established by governmental entities — have been introduced to increase competition in the insurance market and improve affordability of health coverage over time. Governmental authorities can either directly administer these plans or establish a public–private partnership whereby the state sets requirements for private health plans to offer coverage.

Absent federal action, several states like Washington, Colorado, Nevada, and Minnesota have developed their own public option plans, with many other states in the process of developing plans.2 These plans rely on price caps or regulations, such as a requirement that insurers offer a public option plan to participate in Medicaid.3 To date, however, they have had little success in attracting enrollment or increasing competition among insurers to lower premiums.4

We propose a different type of public option plan for California. It would be based on the state’s “delegated model” of health care: provider organizations accept the financial risk of delivering health services, and their earnings are linked to their ability to keep patient care costs within a budget. Below we describe this new approach to a public option, which we call Golden Choice, and evaluate its potential impact on consumers’ health insurance premiums.

The Case for a Public Option in California

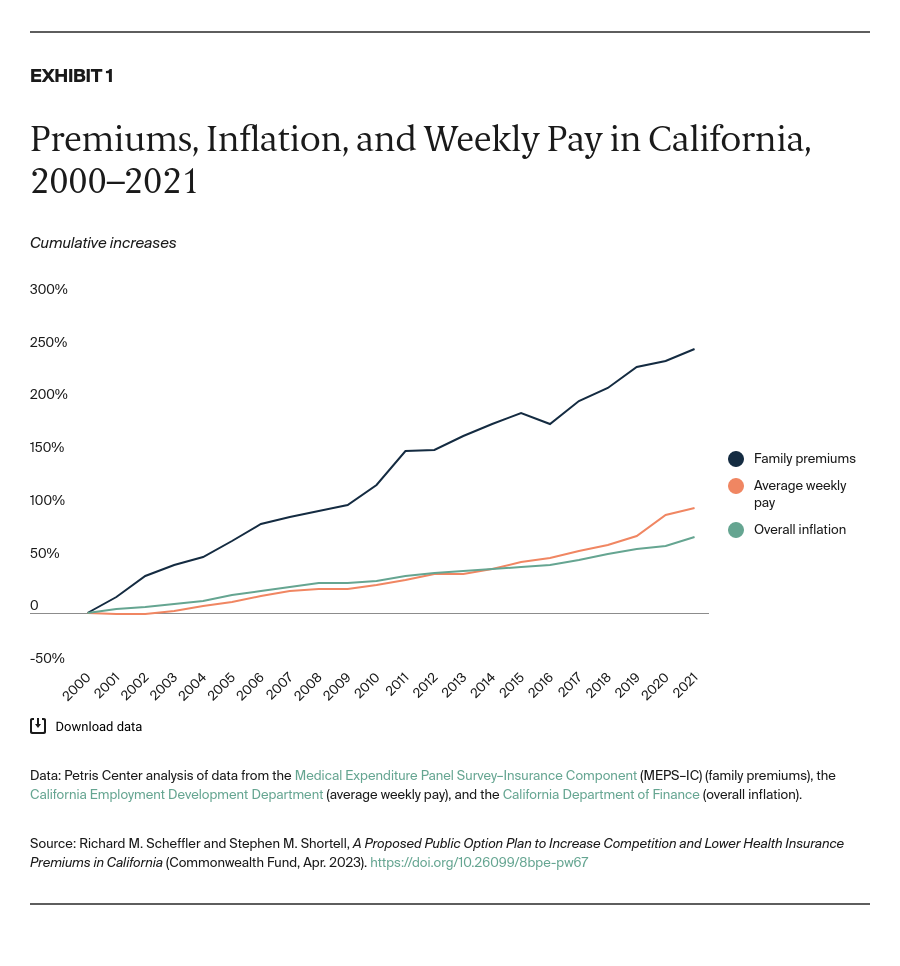

The gap between the rate of health insurance premiums and average weekly pay is widening in California (Exhibit 1). From 2000 to 2021, health insurance premiums increased 251 percent while average weekly wages doubled. Premiums and deductibles have risen so much that they now are equal to as much as 12 percent of the state’s median income.5 This trend is even worse among Hispanic and Black Californians, whose incomes tend to be significantly lower than those for other racial and ethnic groups in the state.