Abstract

- Issue: The high cost of long-term care puts financial pressure on families and worsens inequities in many developed countries. But compared with the United States, many other high-income nations have adopted more comprehensive approaches to financing long-term care services.

- Goal: To understand how different countries and U.S. states finance long-term care.

- Methods: Analysis of long-term care cost data in the U.S. and spending data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development for 12 high-income countries.

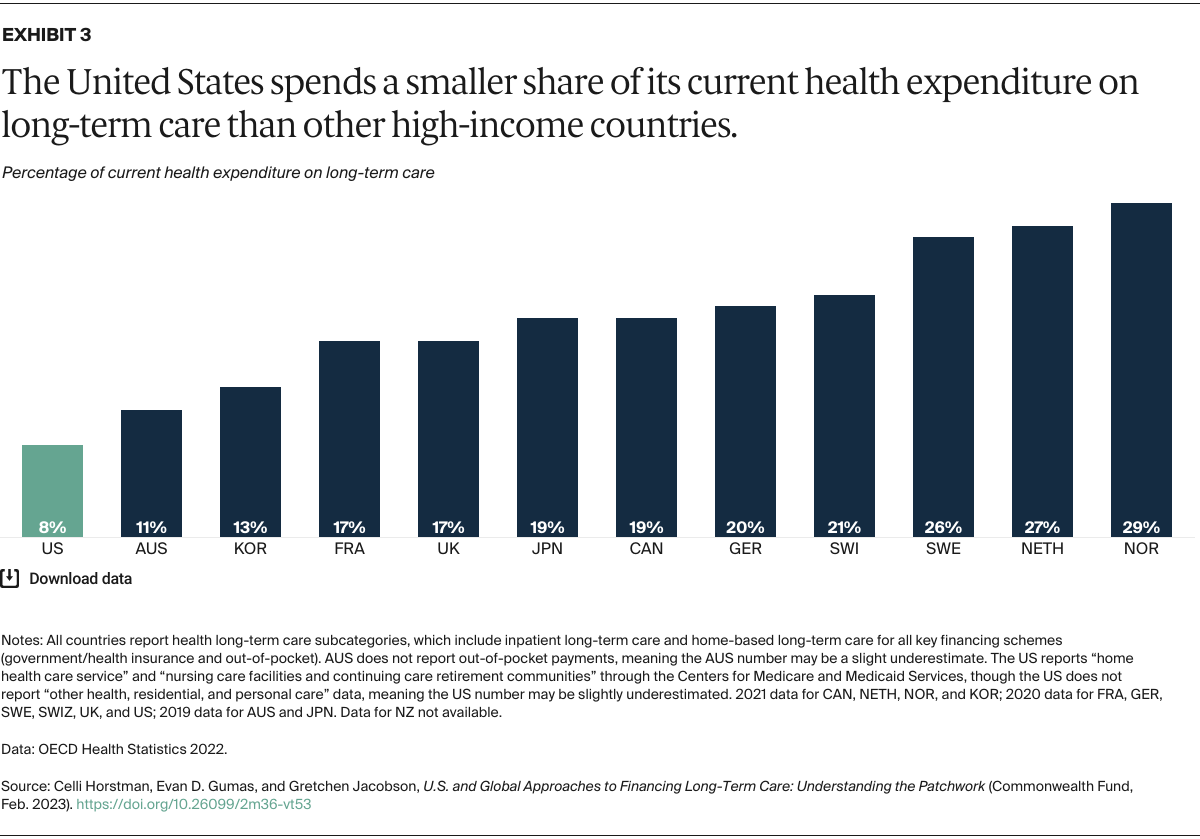

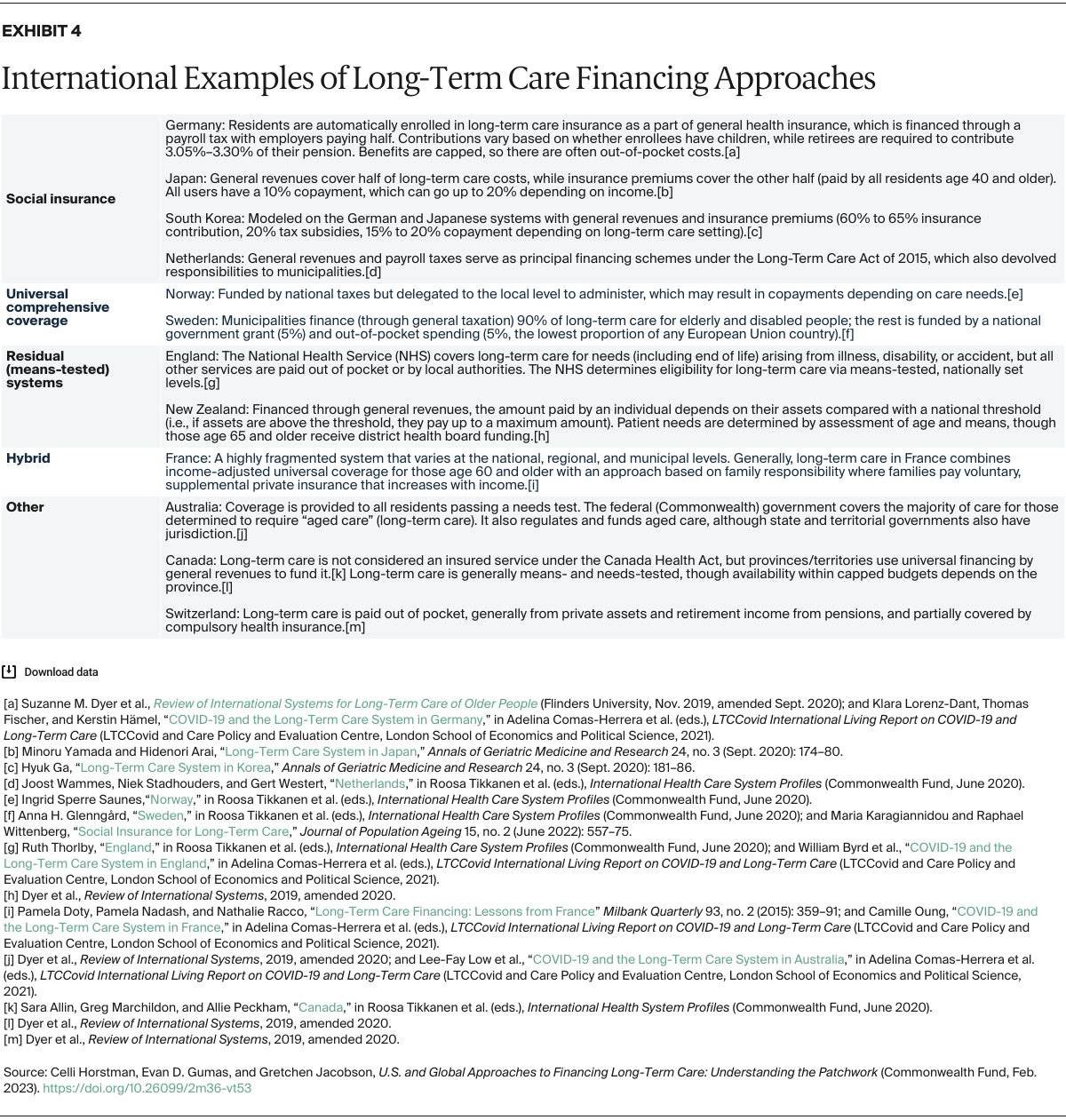

- Key Findings and Conclusion: U.S. spending on long-term care is proportionally the lowest among high-income countries, and there is no single approach to funding this care. In many of these countries, and in certain U.S. states, there is broad eligibility for long-term care benefits or substantial financial assistance, paid mostly through the government or social insurance programs. Common approaches to financing include social insurance, universal comprehensive coverage, residual (or means-tested) systems, and hybrid strategies. Insights from international models and from innovative funding mechanisms being tested by some U.S. states could inform future efforts to reduce the financial burden of long-term care on U.S. families while reducing income- and race-based inequities.

Introduction

Most United States adults age 65 and older will need long-term care toward the end of their lives.1 Long-term care, provided in the home, community, or in institutional settings like a nursing home, includes medical care as well as personal, nonmedical care for people who are unable to perform activities of daily living, like cooking or bathing. Some services also may support social needs for those unable to perform what are known as instrumental activities of daily living, such as shopping or medication management.

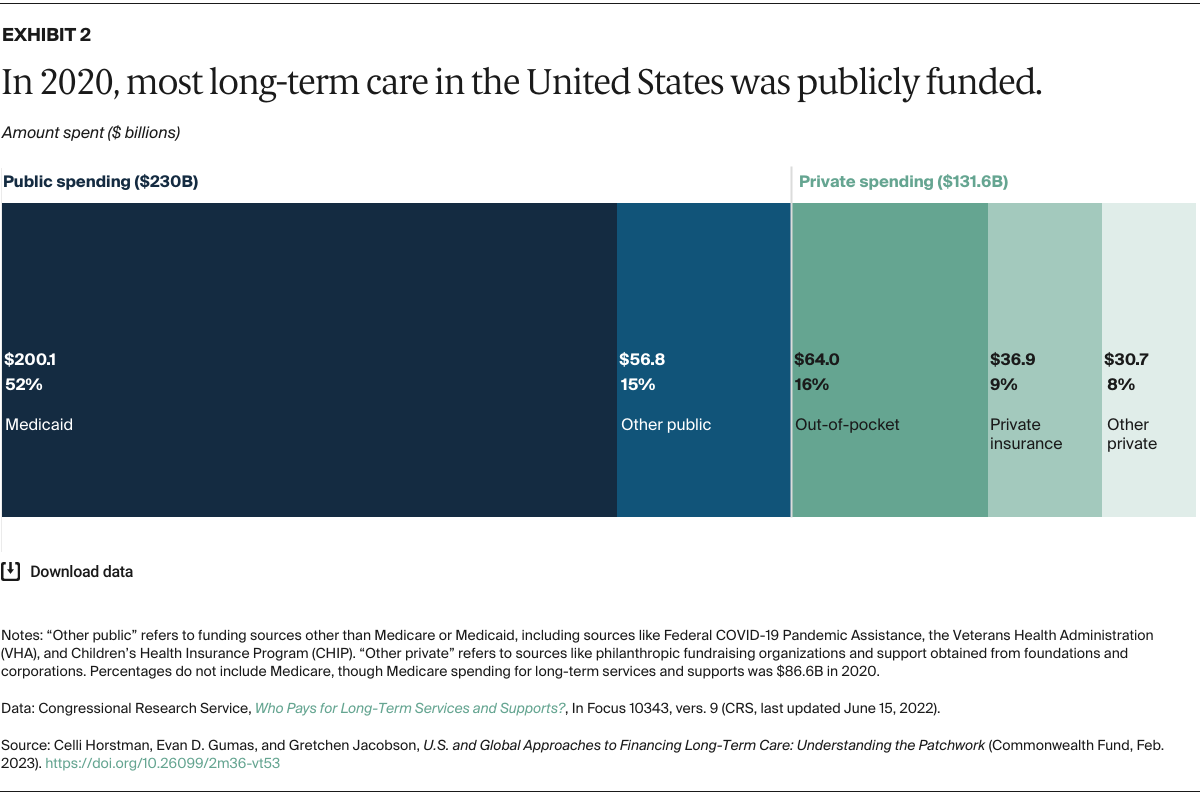

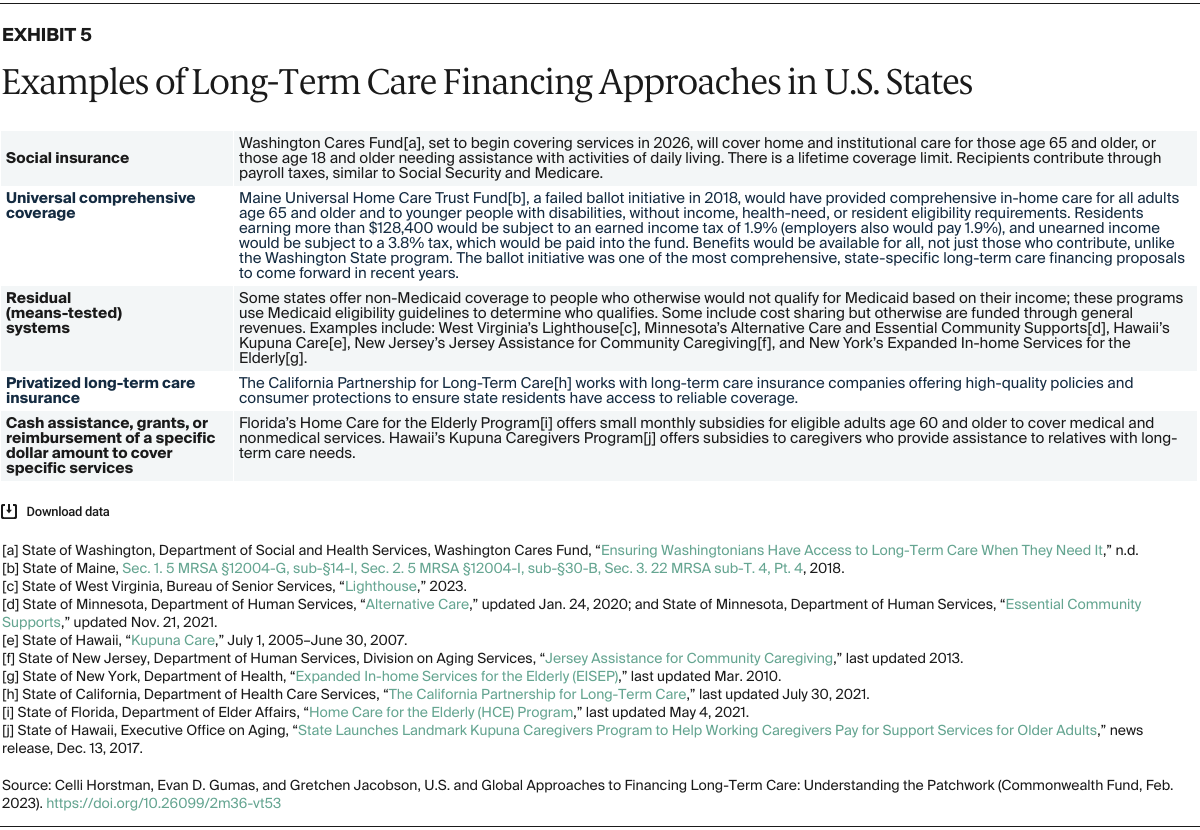

In 2018, more than 5 million people in the United States used home health care, including adult day care or home health agency services, and nearly 4 million people resided in nursing homes or residential care communities.2 Despite the widespread need for long-term care, the U.S. has no national program to cover the costs of long-term care. While certain states have implemented their own programs, the resulting patchwork of funding has left many Americans with no sustainable way to pay for the services they require. Other developed countries have comprehensive, national long-term care financing systems featuring broad eligibility and high levels of financial support.

In this brief, we analyze data from multiple sources on long-term care costs in the U.S., as well as spending data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), to better understand long-term care financing strategies in 12 high-income countries. In addition to these data, we synthesized initiatives to long-term care funding in these 12 countries. (For details, see “How We Conducted This Study.”)

Since the U.S. does not have a national funding strategy, we also focused on individual state approaches. International and U.S. state approaches may provide insights to policymakers seeking to advance comprehensive long-term care funding.

Long-Term Care in the United States: Who Bears the Costs?

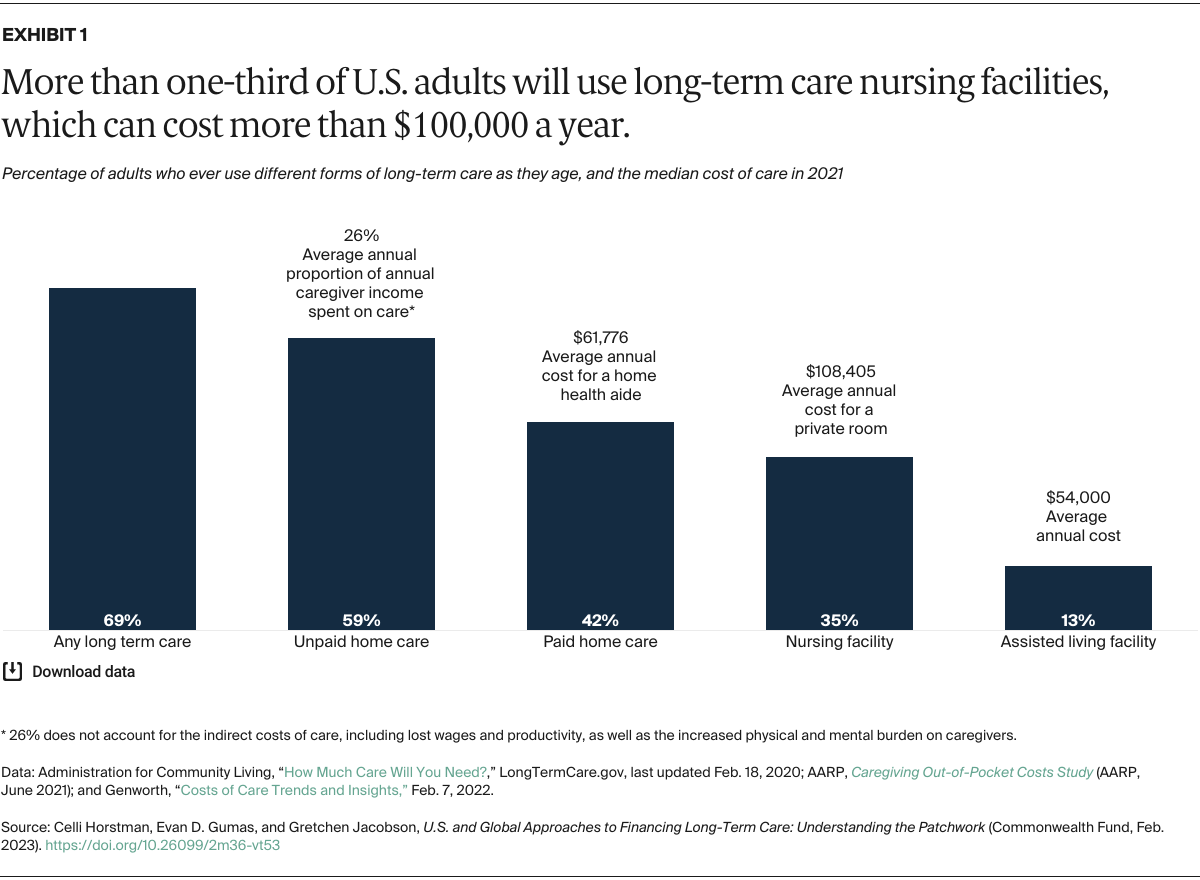

In the U.S., long-term care costs individuals and their families thousands of dollars annually, with nursing home care often costing more than $100,000 a year (Exhibit 1). Given that many who use these services will need it for at least one year, costs can quickly become burdensome.3