One SBM official spoke glowingly about the benefits of annually updating their language access plan: “We really utilize our language access plan as a guide for us in moving forward and making sure that we’re actually hitting those promises which we have made publicly.” Another SBM official acknowledged that creating a language access plan may feel “daunting and overwhelming,” but their team was able to refer to plans from peers as models and ultimately found it “very helpful.” In particular, drafting a language access plan forced them to “think more about what [they’re] not offering” and work to fill those gaps.

However, other interviewees suggested a marketplace- or agency-specific language access plan may do little more than check a box for compliance purposes if officials do not regularly consult or update it, or if it merely establishes the bare minimum requirements an SBM is already exceeding. Thus, the value of a language access plan depends on how SBMs apply it.

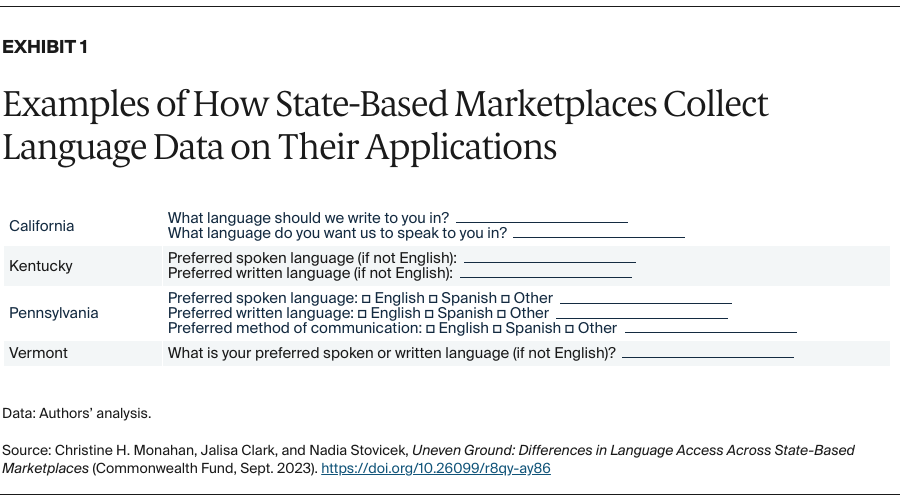

States have not standardized how they collect language data.

State-based marketplaces are not required to collect enrollees’ language data, but SBMs may put their resources to better use if they know the language needs of their enrollees.9 To this end, most SBMs collect both the preferred spoken and written language from the primary point of contact applying for coverage; the remainder ask more generally for this person’s preferred or primary language (Exhibit 1).

Just four SBMs — California, Colorado, Kentucky, and Minnesota10 — collect language data for other household members seeking coverage as part of the application process.11 This can provide an SBM a more complete picture of the language needs of its enrollees, capturing circumstances such as when an 18-year-old English speaker applies for coverage for himself and his LEP parents.

States’ use of applicants’ language data varies. Some states may use language data to identify whether correspondence should be sent in Spanish, while other SBMs put it to broader uses. New York, for example, uses these data to inform outreach efforts and staffing for their call centers. Other states rely on these data to shape enrollment efforts; set priorities for their navigator programs, which help individuals compare and enroll in marketplace coverage; and translate website or other educational content.

In interviews, SBM officials also identified state population-level information and reports from navigators and assisters as important language data sources. These sources can be particularly important for outreach and marketing efforts because LEP individuals have higher uninsured rates.12 Some SBMs, such as Nevada and New York, also track the uptake of their language resources through information on the usage of translated materials from their distribution center. But SBMs may not have readily available data on all the languages spoken by the populations they serve, and usage data could be wielded to equate low uptake with low need when people with LEP may just be unaware of the resources.

Navigators and telephonic interpreting services play critical roles in meeting oral language assistance needs.

SBMs can provide oral language assistance through qualified multilingual staff who communicate directly with LEP individuals, or indirectly through qualified interpreters, often accessed over the phone. According to interviews, the first approach is preferred by many marketplace customers because it is more efficient and can foster greater trust because it does not require bringing an unknown third party into the conversation. Garnering trust can be particularly important for serving immigrant populations and others potentially wary of interacting with government agencies.13

Two-thirds of all SBM call centers have one or more multilingual representatives who can speak Spanish, while just four SBMs — California, New York, Rhode Island, and Washington — have representatives who speak additional languages (Appendix). In place of multilingual call center representatives, the D.C. marketplace diverts relevant cases to marketplace staff certified to provide direct services in Amharic and Spanish. Vermont does the same for Spanish. To the extent multilingual representatives are not available in a caller’s preferred language, call center representatives in every SBM have access to telephonic interpreting services that can typically support more than 200 languages.14

Otherwise, SBMs primarily provide multilingual language services through their navigator/assister programs. California offers navigator services in the greatest number of languages (111), but only about half of SBMs have navigators with staff that, collectively, can speak 15 or more languages (Appendix).

SBM websites generally allow users to search for navigators/assisters by language(s) served, and some also enable consumers to search for brokers on this basis. But this depends on websites being translated into other languages so users can utilize this function. Additionally, the geographic reach and capacity of multilingual navigators may not be adequate.

In interviews, SBM officials shared some best practices to meet the oral language needs of the diverse populations they serve. These include:

- Designating phone numbers for higher-volume languages to simplify access and reduce wait times (such as, “llame a XXX-XXX-XXXX para español”).

- Offering callers the choice to hold to speak with a representative in their language or to use an available interpreter.

- Ensuring there is one or more Spanish bilingual individual(s) at all outreach and enrollment events to assist Spanish-speakers without having to rely on telephonic interpreting services.

- Establishing in-language callback services, where consumers can request a return call in their preferred language.

The availability and quality of written translations varies significantly.

As previously stated, federal regulations require SBMs to provide written translations at no cost to people with LEP. At a minimum, SBMs must include taglines on critical documents directing people to language services, such as a language line and, in the case of California and New York, website content translated into Spanish.15 Beyond this, SBMs take varying approaches to translating written materials.

SBMs in Idaho and Maine reported that their applications were available only in English for the 2023 open enrollment period. Washington, in contrast, translates its paper application into 15 languages. Most of the other surveyed SBMs have applications available in Spanish, and D.C., Minnesota, New York, and Rhode Island also translate their paper applications into at least one other language.

Every surveyed SBM except Maine reported having some website content translated into Spanish and additional languages. However, the scope and method of translation varied. Nearly half of SBMs, including the three that rely on the federal HealthCare.gov platform, had fully Spanish-language websites created by human translators for the 2023 open enrollment period. In contrast, at least eight used machine translation software like Google Translate to translate all or portions of their websites, which is known to result in frequent errors.16

Proposed regulations to Section 1557 would require SBMs to have a qualified human translator review any machine-translated materials that are “critical to the rights, benefits, or meaningful access of an LEP individual; when accuracy is essential; or when the source documents or materials contain complex, non-literal, or technical language.”17

SBM officials interviewed were aware of the limitations of machine-translation software. One official noted there was a “constant issue of [Google Translate] not translating correctly,” admitting it was used as a “last resort.” Another framed it as a “trade-off” between “machine translation or nothing,” emphasizing that they try to have a native speaker review translations and “make sure that they actually make sense to a human.” Officials revealed that it is common for SBMs to turn to their own staff or navigators for this type of assignment, but these individuals may not be qualified to provide these skilled services. In addition, marketplace staff or navigators may not speak all the needed languages and they may have limited capacity to take on additional tasks. Unfortunately, these concerns are particularly acute for less common languages where machine translation may perform especially poorly.

Conclusion

The variation in state-based marketplace language access policies and practices highlights the significant latitude afforded by current federal laws and regulations. This finding was reinforced by interviews, in which state officials consistently reported that federal language access requirements failed to play a significant role in their decision-making. Instead, officials espoused a deep commitment to meeting their customers where they are. But how this can manifest varies, with interviewees suggesting that they often make decisions on the fly, rather than after robust strategic planning.

Interviews also revealed that SBMs are independently engaging in many of the same activities, such as translating similar documents and creating standardized glossaries for consistency in interpreting or translating health insurance terms. Nonetheless, there appears to be minimal, if any, federal guidance or interstate coordination concerning these activities. The federal government’s lack of engagement is particularly notable because it has intervened in similar circumstances. For example, the Internal Revenue Service and Federal Emergency Management Agency routinely translate forms and resources into an array of languages.18 Even if SBMs needed to modify forms to account for differing state eligibility rules, the availability of template translations or standardized translation glossaries could reduce the duplication of effort.

Federal policies to update and standardize language access requirements would promote greater consistency across states and likely benefit people with limited English proficiency. This could include reforms such as requiring all SBMs to develop a written language access plan and collect language data in a standardized fashion. To minimize burdens on SBMs and reduce the duplication of effort, such federal policies could provide additional guidance and resources, increasing state-based marketplaces’ operational efficiency and impact.