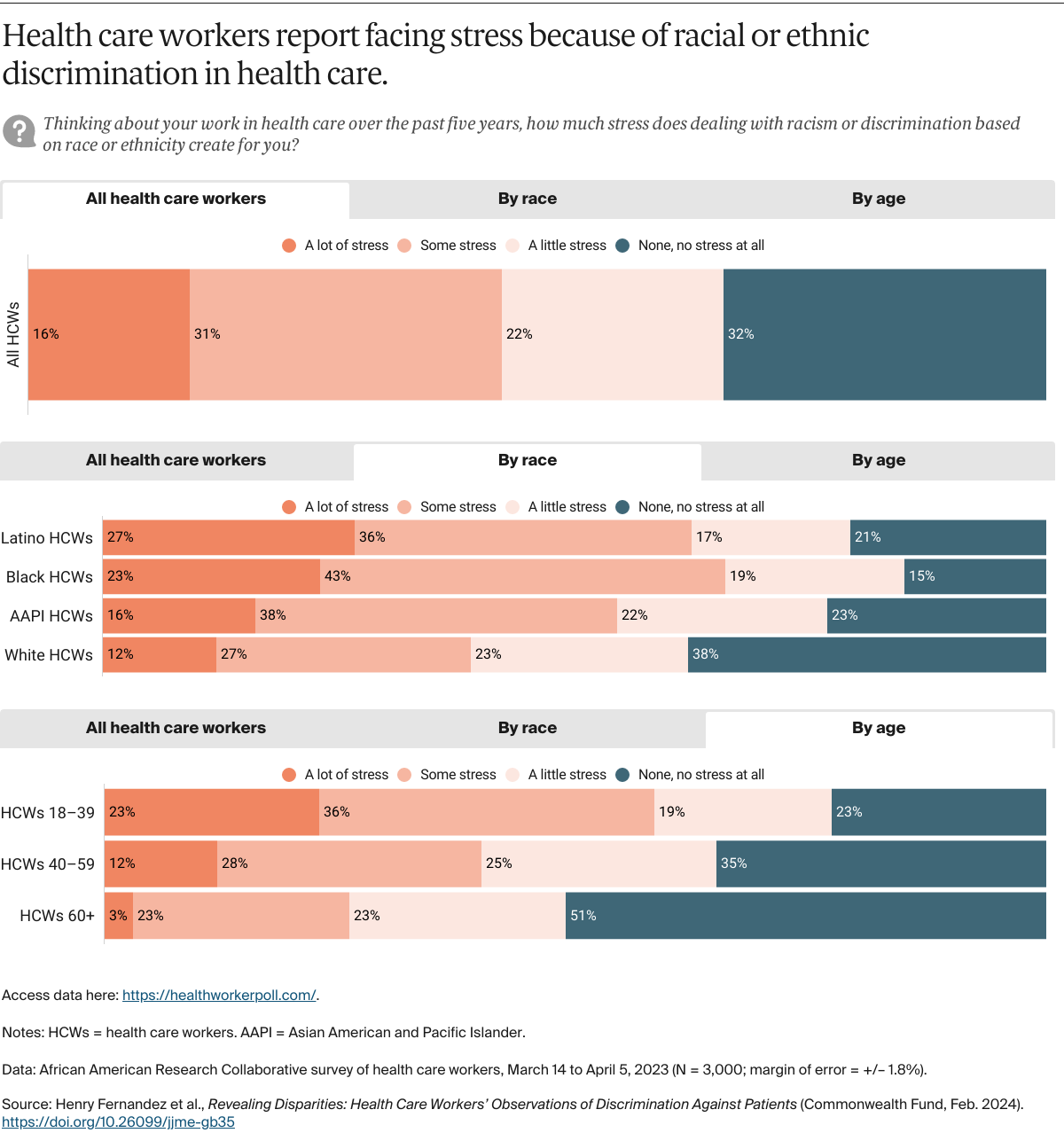

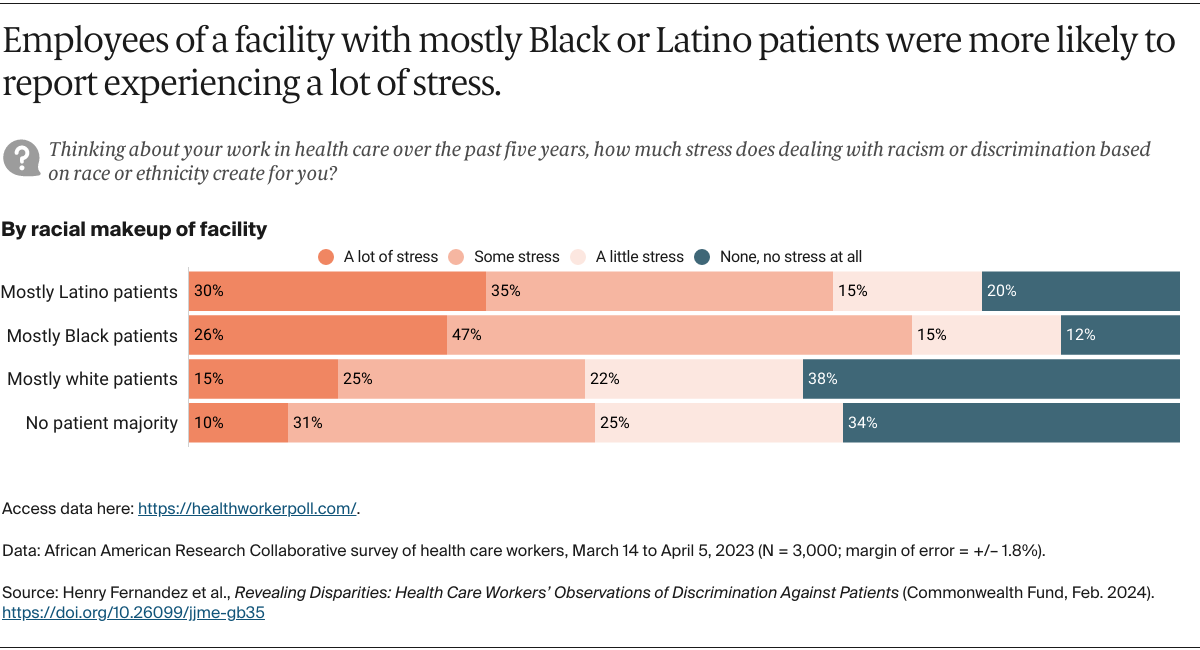

Racism in health care impacts not only patients but also large numbers of health care workers. Just under half of health care workers, and majorities of Black, Latino, and AAPI health care workers, report that dealing with racial or ethnic discrimination in health care creates some or a lot of stress for them. The likelihood of experiencing stress related to racism varies by the race and age of health care workers and the race or ethnicity of patients in the facility where respondents work. Those most likely to report experiencing a lot of stress from dealing with racism are Black and Latino workers, young health care workers, and those employed in facilities with a majority of Latino or Black patients.

Discussion

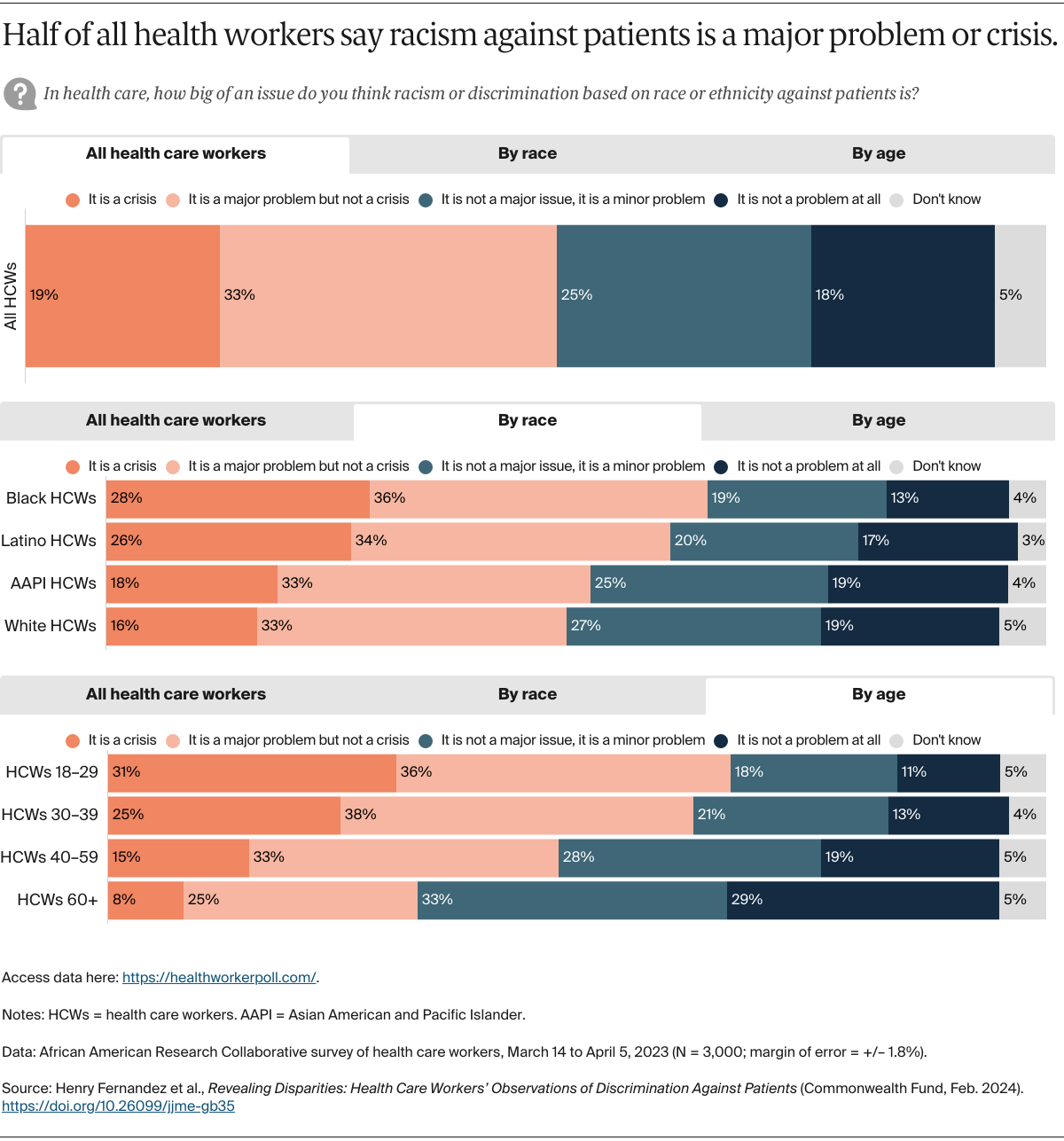

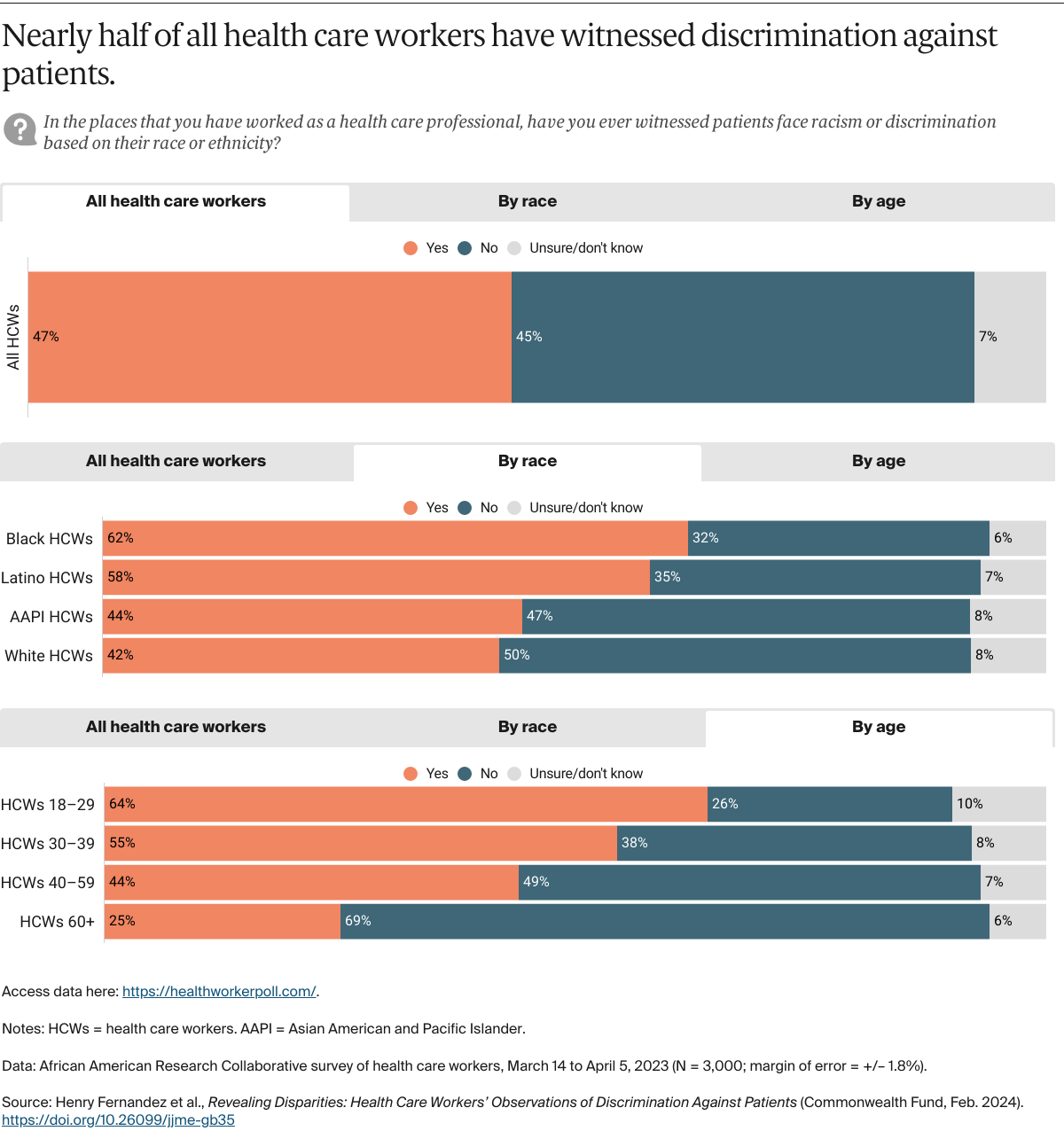

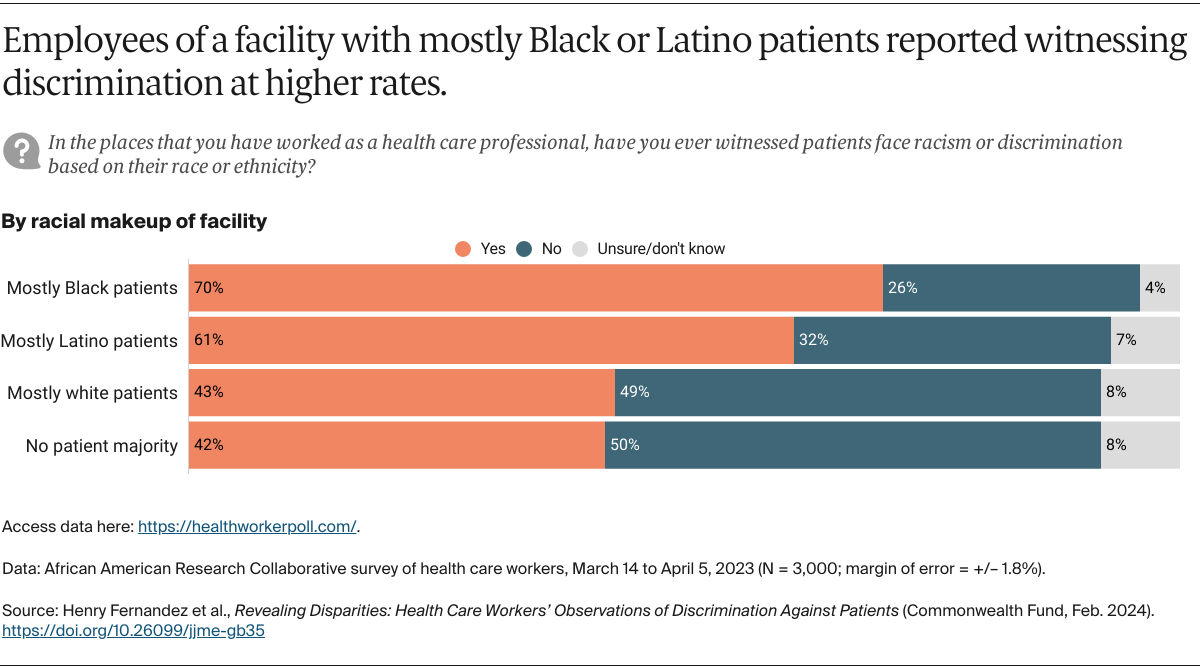

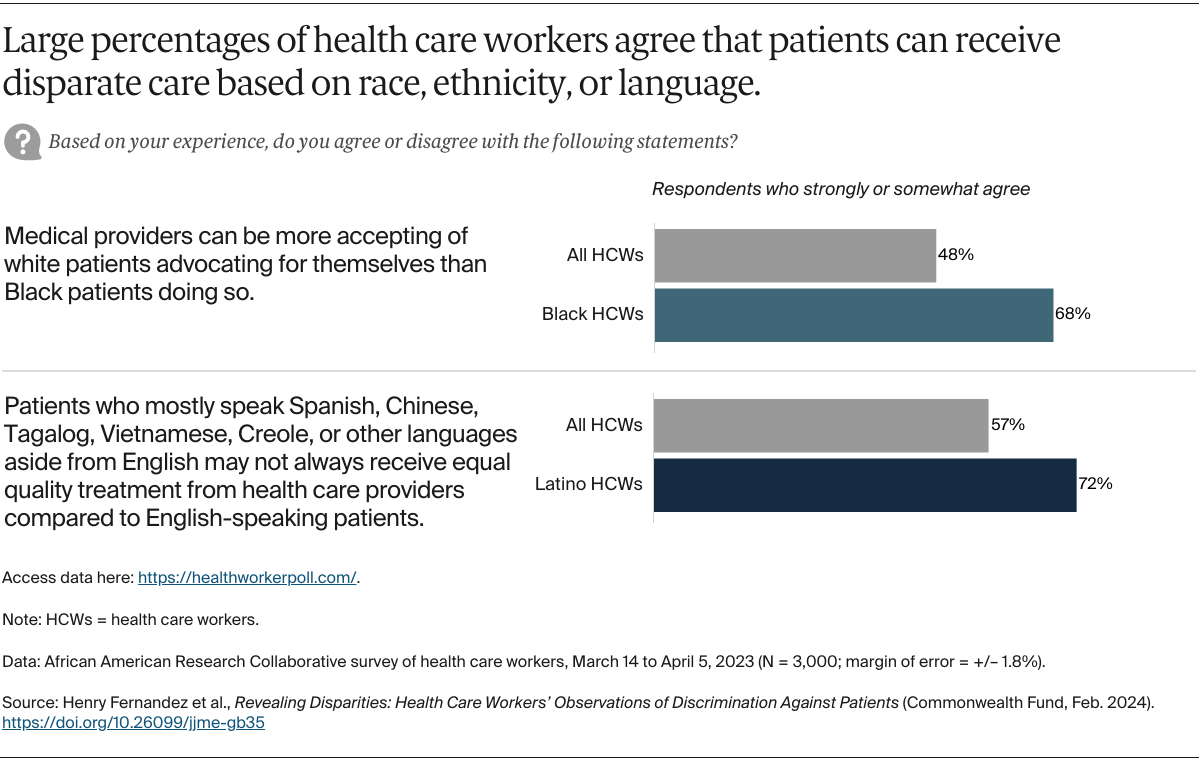

Our research indicates that about half of health care workers view discrimination against patients as a crisis or major problem. Their concerns appear grounded in real-world experience, as similar percentages report having witnessed discrimination against patients — with many saying their most recent observation occurred in the past three years. Even among those demographic groups less likely to report witnessing discrimination, the percentages saying they have witnessed discrimination remains troublingly high. Our results reflect a problem recognized by significant percentages of health care workers across race, ethnicity, gender, age, region of the country, job type, and type of health care facility.

Discrimination’s impact on health workers. Discrimination against patients also takes a serious toll on health care workers’ well-being. This is particularly concerning as medical facilities seek to hire and retain clinicians and other health workers at a time of widespread staff shortages across the health care field. With the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting a nationwide shortfall of some 275,000 nurses by 2030, continuing discrimination within the health system will likely undermine efforts to fill that and other hiring gaps.4

Black and Latino health workers in our study experienced stress resulting from discrimination in their workplaces at alarmingly high rates compared to their white counterparts. This should be concerning to medical schools, nursing schools, and hospitals trying to diversify the health care workforce. A recent study found that health care workers who witness racism by other clinical staff often lack options allowing them to discuss and report such experiences.5 Our research indicates that health care workers also struggle with the added emotional labor of dealing with discrimination in their workplaces — a heightened concern for those attempting to recruit and retain nurses, physicians, and other staff of color.

Generational differences. We are struck by the significant differences in health care workers’ responses based on age. Younger workers are more likely than their older colleagues to say they have witnessed discrimination against patients, more likely to report that racism against patients is a crisis, and more likely to experience stress as a result. Further research could clarify these generational differences in experiences of racism and potentially inform efforts to prevent younger health workers from leaving the profession.

What We Can Do

Health system leaders and policymakers have the responsibility to create safer and more equitable care settings for patients and the people caring for them. In our survey, we tested multiple strategies to see which of them health care workers thought would be most effective at decreasing discrimination based on race or ethnicity in health care. The following solutions were deemed very or somewhat effective by two-thirds or more of the workers we surveyed. They can be initial steps in addressing discrimination in health systems, with knowledge that they will be generally seen as worthwhile by a solid majority of the workforce.

Provide an easy way for patients and health care staff to anonymously report situations involving racism or discrimination. Health care systems need to create simple mechanisms for health care workers to anonymously report instances of discrimination or racism, and for patients to report concerns on how they are treated. Anonymous reporting presents difficulties in ensuring accountability and facilitating follow-up actions. By implementing confidential reporting methods, we can maintain follow-up procedures while protecting the identity of the person making the report. Moreover, it is crucial to enhance patient awareness of the available reporting options within health systems.

Examine policies to be sure they result in equitable outcomes. Health care organizations should regularly conduct comprehensive reviews of their policies and procedures to ensure they are oriented toward equitable health care outcomes for patients of color as well as equitable treatment of health care workers. Toward this end, several health systems are implementing “racial equity progress reports.”6 In addition, the American Medical Association has adopted a strategic plan to advance health equity, and the Association of American Medical Colleges has developed a framework for addressing and eliminating racism in academic medicine.7

Require classes on discrimination at professional schools. Medical, nursing, and other health professional schools should include courses on discrimination, race, and racism and make these required for all students. Schools also should review curriculum to remove any inappropriate references to race or ethnicity.

Create opportunities to listen to patients of color and health care professionals of color. Nearly seven of 10 health care workers endorse efforts by health care organizations to create opportunities to listen to patients of color and health care professionals of color. Support jumps to three of four for Black, Latino, and AAPI health care workers and a similar proportion of those who serve primarily Black and Latino patients.

Examine treatment of non-English-speaking patients. Three-quarters of Latino, AAPI, and Black health care workers say that evaluating how non-English speakers are treated to identify whether additional or improved translation and staff training are needed is an effective strategy.

Train health care staff to spot discrimination. Health care workers require training to ensure they can recognize instances of discrimination and bias within health care interactions and understand how discrimination can lead to poor health outcomes.