By Martha Hostetter

Summary: Using Medicaid Transformation Grant funds, Alabama created a health information exchange system with clinical support tools and e-prescribing functions, called QTool. The goal is not to have QTool become the dominant electronic health record system in the state, but rather to have it serve as an electronic infrastructure linking together disparate data sources, so that providers know as much as possible about their patients. In a pilot test that began in July 2008, 50 primary care physician practices have been using QTool to manage care for their Medicaid patients. Use of the tool has gradually increased as the state enhanced the system, offered training, and increased financial support to help practices integrate the system into their workflow.

Issue: In our fragmented health care system, reports from specialists or laboratories may not be available to primary care physicians when they need to make decisions about their patients' care. In addition, providers are often unaware of the various medications their patients are taking or of their previous treatments and diagnoses—leaving considerable room for duplication and error. Meanwhile, large payers such as Medicaid are often frustrated in their attempts to evaluate the health of their patient populations and target improvement initiatives where they are needed most.

Health information systems that provide access to comprehensive patient information at the point of care and enable information exchange across care settings have the potential to improve health care quality, safety, and efficiency.

Alabama is one of 35 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico that received Medicaid Transformation Grants from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to support initiatives aimed at improving the effectiveness and efficiency of care in the Medicaid program. Like most of these states, Alabama is using the grant funding to deploy health information technology. Its "Together for Quality" program seeks to create a statewide electronic health information system to improve the quality of care for Medicaid beneficiaries, particularly those with chronic conditions. In Alabama, chronic conditions are responsible for seven of 10 deaths and 75 percent of all health care costs.1

Alabama also hopes that having statewide electronic health information will help it prepare for public health emergencies. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, hundreds of evacuees arrived in Alabama without prescription medication, medical records, and—in some cases—a history of their medical conditions.

Objective: Alabama aims to improve the quality of care for Medicaid beneficiaries and control health care costs through development of a statewide electronic health information system.

As an initial step, the state created a health information exchange system with clinical support tools and e-prescribing functions, called QTool. The goal is not to have QTool become the dominant electronic health record system, but rather to have it serve as an electronic infrastructure linking together disparate data sources, so that providers know as much as possible about their patients.

Organization and Project Leadership: The Together for Quality (TFQ) initiative is led by the Alabama Medicaid Agency. Kim Davis-Allen, B.S., is the project director and Carol H. Steckel, M.P.H., Medicaid commissioner, provides leadership. Janet Bronstein, Ph.D., professor in the department of health care organization and policy at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, is leading an evaluation of the TFQ pilot project.

Alabama formed a stakeholders' council that includes health care providers and professional associations, other state agencies, private health plans, health care purchasers, health information technology entities, business groups, academics, patient groups, and quality improvement organizations. The council has a steering committee and clinical, financial, policy, privacy, and technical workgroups.

Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Alabama, which covers about 80 percent of the state's insured, non-Medicare population (Medicaid covers most of the remaining insured residents), also has been an active participant in the planning and deployment of QTool, which will supersede an electronic health record system that BCBS had been promoting.

Target Population: TFQ aims to improve the quality of care for Alabama's Medicaid beneficiaries, particularly those with chronic conditions such as diabetes or asthma.

Key Measures: To assess the adoption of the health information system by primary care practices, the Medicaid agency is monitoring the number of visits to the QTool Web site and the number of electronic prescriptions made.

When the grant ends in March 2010, Alabama will gauge success not by how many doctors use QTool, but whether their performance on process-of-care measures improves. Measures currently being tracked include: receipt of eye exams, appropriate tests, and flu shots among diabetic patients; and receipt of flu shots, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and controller use among asthma patients.

Evaluators will solicit feedback from providers on the effectiveness of the training, ease of use of the QTool, and value of information available. A telephone survey of beneficiaries will assess the impact of the TFQ pilot program on patients.

Timeline: Alabama received $7.6 million from CMS to fund the TFQ initiative between 2007 and 2008; the state has received a no-cost extension through March 31, 2010, to further its grant work.

Process of Change: The TFQ initiative focuses on three activities:

- development of QTool, a health information exchange system with clinical support features and e-prescribing;

- implementation of a care management program, known as Q4U; and

- creation of a patient data hub for the exchange of information among Medicaid and other state health and human services agencies, known as Qx.

This case study focuses on the development and implementation of QTool.

Together for Quality builds on Patient 1st, a primary care case management program that offers Alabama's Medicaid providers financial incentives to serve as a medical home for beneficiaries. Participating providers earn $1.60 per patient for ensuring 24/7 coverage, taking part in prior authorization programs, and following other protocols. Providers are paid an additional $1 per patient if they use an electronic health record system. About 420,000 patients and 1,083 providers (either physician groups or individual physicians) are enrolled.

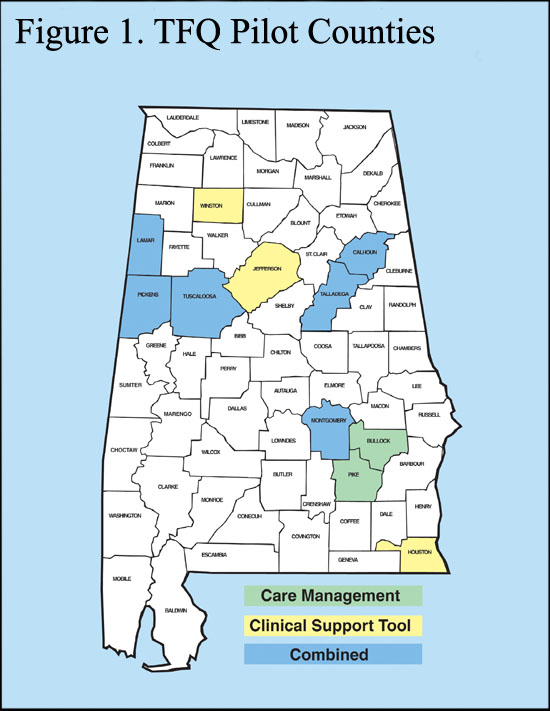

Alabama is piloting QTool among Patient 1st primary care providers. The pilot program targets 11 counties: in two counties, practices are engaged in traditional care management (i.e., the Q4U program, which uses licensed social workers as care coordinators to ensure patients understand and adhere to recommended treatment); in three counties, practices are using the QTool only; and in six counties, practices are using both care management and the QTool (Figure 1). This approach will enable a comparative analysis of which interventions are most effective in coordinating and improving care—care management, use of the QTool, or both approaches working in concert, which would indicate that both people and technology are needed to improve care.

All aspects of the pilot focus on patients with asthma or diabetes, two common conditions among Alabama's Medicaid beneficiaries.

Source: Alabama Medicaid, 2009

Alabama began rolling out the QTool to pilot practices in July 2008. Since QTool is Web-based, practices only need computers and a reliable Internet connection to use it. In some cases, the Medicaid agency provided small grants, capped at $5,000 per physician, to help practices purchase hardware or obtain Internet service.

Q Tool is designed to be compatible with any standard electronic medical record platform (e.g., those that use Snomed or HL7 standards). One electronic medical record vendor has now created an automated interface with QTool, and six other vendors are currently working on this capability.

QTool aims to give providers access to patient information when they need it, bringing together all medical claims data from beneficiaries' office visits, hospitalizations, and emergency department visits as well as immunization records, results of laboratory tests, filled prescriptions, and reports of other procedures. It also includes Medicaid's preferred drug list. Beneficiaries can opt out if they do not wish to make their information available, though none have done so. (Currently, medical information on mental health and HIV does not appear in QTool, while the state reviews confidentiality regulations and forges consensus on whether such sensitive information should be displayed.)

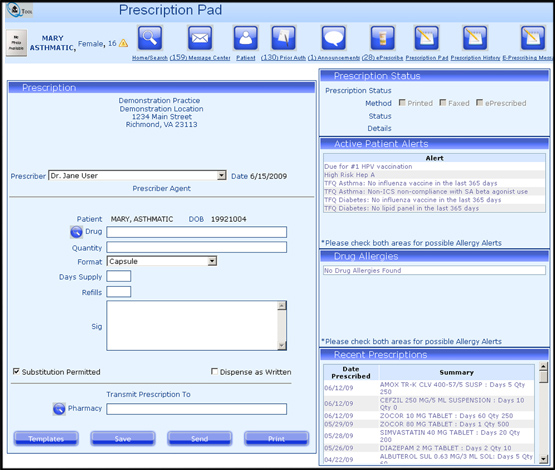

The QTool also provides clinical support, prompting providers when vaccinations, laboratory tests, or preventive care processes are needed (Figure 2). It does so through three types of automated alerts: 1) opportunities to provide recommended care for diabetes and asthma, as identified by the TFQ clinical workgroup; 2) opportunities to order laboratory tests, based on clinical guidelines from the American Diabetic Association and the National Cholesterol Education Program; and 3) notices of patient allergies, which are derived from claims data or entered by physicians. It does not currently have functions enabling providers to call up lists of patient registries, for example of diabetic patients with abnormal lab results.

Figure 2. QTool Prescription Pad

Source: Alabama Medicaid, 2009

New functions will be added to the tool over time. In March 2009, providers began using QTool to prescribe medications electronically—a function many of them took to quickly, says Davis-Allen. In the first two weeks, approximately 300 e-prescriptions were generated by participating providers. In future updates of QTool, providers will be able to add notes, edit records, and refer patients to other providers. In the next six to nine months, providers will be able to use QTool to compare their performance, in terms of patient acuity and health outcomes, to that of their peers. Later, computerized physician order entry will be added, enabling physicians to order laboratory tests and other services.

The QTool vendor provides training in the pilot practices, while Davis-Allen and a part-time staff member provide training for physicians and their office staff on use of the tool at additional practices.

"The in-office training takes anywhere from 10 minutes to over an hour, depending on the user," says Davis-Allen. "I try to give specific examples of how a particular provider might use it. For example, one physician may want to call up a list of all new Medicaid patients to review their medication histories. Another may want to look at ER visits. It takes one-on-one contact to ensure users understand the system and, more importantly, know how to integrate the tool into their daily workflow. Once they are able to see how the QTool data can be used to facilitate decision making, then we will see greater impact on outcomes."

As an example of the value of the system, Davis-Allen recalls a story she heard from a Birmingham primary care physician, whose young patient went to the emergency department (ED) for suspected appendicitis, but was sent home with a clean bill of health. Several months later, the child came for a visit, at which time the primary care physician checked his QTool information. He was surprised to see a diagnosis of renal cysts. The ED had previously sent him a report indicating that the child's appendix and gallbladder were fine, but it did not include the ultrasound report. When the physician requested that report, he found that it did, in fact, note the presence of multiple renal cysts. Since the child's parents had not been told about the cysts, and they were not documented in the report that the ED had sent to the doctor, this diagnosis would have fallen through the cracks if the doctor had not seen it in QTool.

Early Results: As of June 2009, 50 practices, including some 150 individuals, are using the QTool. In addition, one hospital is using the system. Over a period of 90 days of utilization (as of mid-July) there were 4,400 unique visits to QTool, including views of about 2,600 individual patient records.

In a little less than three months (from April through June), there were 1,400 prescriptions written using the QTool. Of the 50 pilot sites, 10 are consistently e-prescribing, while the others are using the system sporadically or not at all—demonstrating the need for further training and encouragement.

Lessons Learned: Implementation of health information technology—particularly user training—is time- and resource-intensive. For that reason, the deployment of QTool has taken much longer than anticipated. (Alabama is not alone here: 99 percent of the Medicaid Transformation grantees had requested no-cost extensions as of January.)

Alabama found that users not only needed training and re-training, but also regular encouragement to use the system. "We got everybody set up on QTool. Then, unless we heard from them, we didn't follow up. Then when we looked at the user statistics, it was like 'Oh wait, nobody's using it.' Users forget their password, forget how to use it, and just generally have a lot of questions during the start-up period," says Davis-Allen. "In hindsight, we would have devoted many more resources to training providers and encouraging their use—with structured steps to follow up."

To sustain provider interest in health information technology, it helps to train office managers and encourage them to champion its use, says Davis-Allen. In addition, peer-to-peer learning can be effective. Davis-Allen has brought together office staff or clinicians from neighboring practices to exchange ideas on how to use QTool. The Medicaid agency is also reaching out to providers through news media, presentations at provider association meetings, Web-based training sessions, and other channels.

It is often best to roll out new technology systems gradually, addressing user problems and adding new functions over time. For example, TFQ leaders heard from physicians that being required to enter information into QTool would be a turnoff, since most of them maintain paper-based medical records and do not want to have to also maintain electronic records. Therefore, the state made the initial version of QTool "read-only," creating time for clinicians to become accustomed to the system and see its value. The current version enables providers to enter information, though less than 1 percent of participating providers have done so.

Integrating new technology into existing workflows is critical to success. QTool also provides a "value-added" tool, since it gives providers access to data they otherwise would not have.

Eventually, however, Alabama will have to integrate QTool with legacy systems, including paper-based medical records. Experience from other states shows that providers' want health IT systems to provide "one-stop shop" solutions, enabling them to perform multiple tasks, such as checking drug formularies, handling administrative functions, and ordering tests or treatments, in a single application.

Alabama's experience shows that strong leadership is crucial to the success of large-scale IT projects. Even if states do not want to be in the business of creating electronic health record systems, they can create the architecture on which to build data exchange between public and private stakeholders, help set policies in regard to governance and privacy issues, and make the case to both providers and patients that health information technology can improve care.

Alabama's partnership with BCBS is crucial to the success of the TFQ program. For enrolled BCBS providers, the private insurer has made its medical and pharmacy claims data available through QTool, so that a patient formerly covered by BCBS and now covered by Medicaid would have a complete medical history available. Other states with greater numbers of competing private insurers may find it harder to forge such collaborations among public and private payers.

"Communication of the vision has been crucial to getting buy-in from BCBS. Without a state-level vision, the different stakeholders are likely to continue 'silo-ing' their data," says Davis-Allen. "Our ultimate goal is that information truly follows the patient. This means that wherever the patient goes for care, their information should be available regardless of where—or who—originally generated it, and regardless of payment source."

Next Steps: Beginning this September, QTool will be rolled out to Patient 1st providers who have not been involved in the pilot test (the rollout will exclude those in control counties). The state will help such practices make the transition from use of the BCBS electronic health record system to use of the QTool. Starting January 1, 2010, Patient 1st providers will be required to use QTool to receive the extra dollar in per-patient case management fees that is now allocated for use of any electronic health information system.

Beginning in April 2010 (after the pilot program is completed), Alabama will begin to roll out QTool to practices statewide.

Eventually, the Medicaid agency plans to use the information in QTool to proactively assess care and target improvement initiatives. It will pave the way to evaluate the quality of patient care according to outcomes and provide data to inform pay-for-performance and disease management initiatives. The clinical workgroup is currently developing recommendations for care processes for cardiovascular diseases, stroke, obesity, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; these recommendations will be implemented into QTool's clinical support tools.

In the longer term, Alabama hopes to give patients access to their medical information, to help them manage their own conditions and communicate with providers about their care.

"We began TFQ with a vision of connecting patient information among all payers," says Medicaid Commissioner Steckel. "Thanks to the ARRA federal stimulus, we will be able to further that vision."

Implications: Research has shown that physicians in urban settings and large physician practices are more likely to adopt and use electronic health information than those in rural and small practices. But the success of the QTool deployment in Alabama—a rural state with many small physician practices—shows that such practices are capable of adopting health IT, in spite of hurdles related to lack of computer equipment, scant resources, and widely dispersed sites.

Still, technology is just a tool: real change will depend on whether providers use IT systems to proactively manage care. Much work remains to be done in creating appropriate incentives and fine-tuning health IT to encourage medication management, review and management of patient registries, care coordination, and other care processes that are likely to improve care and control costs.

"Only when providers truly embrace and incorporate the information and feel comfortable with the information will quality of care begin to be affected," Steckel says.

"Medicaid has to engage physicians in why using a tool like this matters," adds Davis-Allen. "We have to break it down for them so they can understand why—at the end of the day, when you still have patients still in the waiting room—worthwhile to take a few moments and consult QTool."

For Further Information: Contact Kim Davis-Allen, project director, [email protected].

1, Together for Quality Overview, Alabama Medicaid Agency, available at http://www.medicaid.alabama.gov/news/Tranformation_Info.aspx?tab=2.

This study was based on publicly available information and self-reported data provided by the case study institution(s). The Commonwealth Fund is not an accreditor of health care organizations or systems, and the inclusion of an institution in the Fund's case studies series is not an endorsement by the Fund for receipt of health care from the

institution.

The aim of Commonwealth Fund–sponsored case studies of this type is to identify institutions that have achieved results indicating high performance in a particular area of interest, have undertaken innovations designed to reach higher performance, or exemplify attributes that can foster high performance. The studies are intended to enable other institutions to draw lessons from the studied institutions' experience that will be helpful in their own efforts to become high performers. It is important to note, however, that even the best-performing organizations may fall short in some areas; doing well in one dimension of quality does not necessarily mean that the same level of quality will be achieved in other dimensions. Similarly, performance may vary from one year to the next. Thus, it is critical to adopt systematic approaches for improving quality and preventing harm to patients and staff.