Case Study: Institute for Urban Family Health: Using Information Technology and Community Action to Improve the Health of a Diverse Patient Population

By Douglas McCarthy

Summary: A New York City network of community health centers implemented electronic health records (EHRs) as part of its mission to promote equitable access to high-quality care for a socially and culturally diverse patient population. It learned that ensuring equal treatment does not necessarily ensure equal outcomes, emphasizing the importance of broader community interventions in eliminating health disparities.

Issue: Racial and ethnic minorities tend to experience poorer health than white Americans through a complex interplay of social, environmental, behavioral, and medical factors. [1] Eliminating these disparities likely will require multifaceted approaches to engage communities. From a medical perspective, interventions such as tracking and reminder systems have been shown to improve minorities' quality of care. [2] To the extent that information technology can facilitate such interventions, it might accelerate improvement in minority health care and health outcomes.

Objective and Intervention: The Institute for Urban Family Health implemented electronic health records (EHRs) as part of a data-driven strategy to fulfill its mission to improve the quality and availability of family practice services and meet the needs of medically underserved populations.

With funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's REACH 2010 Initiative and other sources, the Institute is collaborating with community-based organizations in a comprehensive initiative. Called the Bronx Health REACH Coalition, it aims to educate and engage the community in actions to eliminate health disparities, focusing on minorities with diabetes and cardiovascular disease living in the Southwest Bronx.

Organization and Leadership: The Institute for Urban Family Health, founded in 1983, operates nine community health centers in the New York City boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. The Institute also runs nine part-time centers for the homeless, two free clinics for the uninsured, a school-based health center, and a residency program in family medicine, all in New York City.

Neil Calman, M.D., is president and chief executive officer of the Institute and a professor of clinical family medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Yeshiva University. He also serves as principal investigator for the Bronx Health REACH Project.

The Institute employs 50 full-time primary care physicians and nurse practitioners, all of whom participate in a two-day diversity training workshop as part of an organizational commitment to cultural competence. A social work staff of 40, including 15 full-time social workers supplemented by part-time students and interns, handles insurance eligibility, case management, and care coordination responsibilities, as well as extensive mental health evaluations and follow-ups. About one-third of Institute staff is bilingual. Spanish-speaking patients are matched to Spanish-speaking clinicians whenever possible, or translation is provided by a bilingual staff member or through telephonic language services.

Target Population: The Institute serves a socially and culturally diverse urban patient population of all ages, including the middle class, working poor, people receiving public assistance, the uninsured, and the homeless. The Institute's family health centers serve primarily black and Latino patients living in designated medically underserved (health professional shortage) areas.

Date of Implementation: The Bronx Health REACH collaborative was formed in 1999; and the Institute implemented electronic health records in the fall of 2002.

Key Measures: Process and care outcomes for diabetes and cardiovascular disease by race and ethnicity and other preventive health measures.

Process of Change

Bronx Health REACH: The Institute collaborated with New York University's Center for Health and Public Services Research and community-based organizations to design, carry out, and evaluate an action-oriented research agenda to identify and address the systemic causes of health disparities.[3] Coalition partners include social service agencies, housing and economic development groups, health care providers, an after-school program, and faith-based organizations.

The coalition conducted a literature review and 10 community focus groups, led by trained community members, to help understand the nature and causes of disparities. Analysis of the personal and family experiences described in these focus groups revealed barriers to health and health care including poverty and life stress, lack of affordable healthy food choices, and poor treatment leading to mistrust in the health care system.[4]

These findings were presented at a series of community meetings and analyzed by working groups to develop a set of related educational and advocacy interventions, including an after-school nutrition program, a fitness program, a community advocacy program, a faith-based initiative, an education program for seniors, and a seven-point policy agenda. [5]

Electronic Health Records: Before electronic health records were implemented, managers at the Institute were frustrated by their inability to comprehensively measure quality of care. Provider-specific performance profiles prepared by managed care plans lacked consistency, as they captured only a subset of each provider's patient panel. Quality improvement studies using random samples of records provided snapshots of quality at a point in time, but they could not be used to evaluate and guide ongoing interventions.

After entering into a contract to operate six health centers for an affiliated hospital system, the Institute's leadership recognized that better real-time data were needed to monitor and manage performance across the organization. This realization served as a catalyst for the adoption of an electronic health records system, which the Institute's board endorsed as an innovative way of meeting the organization's mission. With financial assistance from government and foundation grants, the Institute selected a commercial EHR system that could facilitate quality improvements by:

- Improving the organization and legibility of the medical record. Clinicians enter progress notes electronically using tools ranging from shorthand commands to predefined data-entry forms that double as electronic checklists tailored to specific clinical conditions. For example, the form for a well-child visit provides a list of items to be covered during the physician exam and topics for health education counseling.

- Serving as a platform for clinical decision support. The system generates reminders during the clinical visit when patients need preventive services, such as vaccinations, and early detection procedures, such as cancer screenings, blood sugar testing, and cholesterol testing. In addition, disease-specific interventions are recommended based on past and present medical conditions.

- Reducing medication errors and adverse drug effects. When prescriptions are ordered, the system recommends drug dosages and alerts clinicians to drug allergies, contraindications, and potentially harmful interactions.

- Helping clinicians educate patients. Computer monitors are located alongside the physician, in view of the patient, to facilitate communication. The system uses keywords from the patient's record to suggest relevant education materials, which the clinician can print in English or Spanish. The patient's progress over time (e.g., on measures such as cholesterol, blood pressure, weight, or blood sugar levels) can be graphed and reviewed to motivate adherence to medications and lifestyle changes. At the end of the visit, patients receive their lab results and a list of their clinical problems and medications to reinforce physician-patient communication.

- Facilitating follow-up and outreach. The system allows providers to generate letters to patients due for disease-specific services or follow-up care (e.g., diabetic patients with poor blood sugar control on the last HbA1c test who have not been seen in the clinic for the past six months) and enables centralized outreach from two full-time, bilingual support staff who phone patients to schedule follow-up appointments. When patients with a potentially serious health problem (e.g., dangerously high blood pressure level) do not respond to outreach, an Institute social worker will make a home visit to check on them.

- Monitoring performance. Clinical directors meet monthly to review the results of disease-specific quality measures, set priorities for action, and design appropriate interventions, such as adding new system reminders or designing outreach programs.

Managers identify best practices by examining care processes at clinics that have good performance on specific quality measures. For example, a clinic with the best diabetes outcomes turned out to have many patients insured under a plan that paid for nutritional counseling, a service that is often not reimbursed. This finding led the Institute to hire a part-time nutritional counselor and monitor outcomes to determine its effects. Another intervention developed by a student intern, following-up with patients who initially refused a recommended colonoscopy test, led about one-half to change their minds.

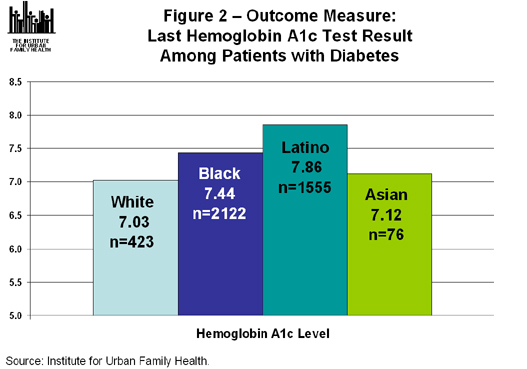

Results: About 80 percent of patients voluntarily provide information on their race and ethnicity when they register. Based on three years of data for patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease, the Institute's clinics provide equal treatment to racial and ethnic groups on all measured care processes studied to date (Figure 1). However, minorities continue to experience worse intermediate outcomes, such as control of blood sugar among patients with diabetes (Figure 2). This finding is prompting further efforts to understand the causes and potential solutions for quality improvement.

Preliminary results from specific interventions include the following:

- Following the implementation of electronic reminders, pneumococcal vaccinations increased from 19 to 296 doses per month; about 90 percent of elderly patients and those with pulmonary disease are being vaccinated as recommended.

- After one clinic's pilot, which added two depression screening questions to the EHR system, the proportion of patients screened for depression increased to 80 percent from a level of about 3 percent in usual practice.

Lessons Learned: An EHR system can be an important tool for improving quality of care and ensuring equitable treatment for diverse patient populations. "We had other ways we could have spent the $2 million this cost us for purchasing and implementing the system, but nothing we could have spent that money on could have saved as many lives or led to the number and extent of quality improvements in the health of our patients," Neil Calman, the Institute's president and CEO, said at a recent congressional briefing. [6]

An EHR system does not guarantee automatic improvements in quality, however, "it is how you use it that determines the results," says Calman. For example, the Institute did not see substantial improvements in performance until the system's decision support components—the prompts and reminders mentioned—were implemented. Calman believes that the system's greatest contribution is transforming the physician–patient relationship by enabling better communication. Electronic reminders can help physicians overcome subtle biases that could affect their clinical judgment, he says.

The Institute's experience suggests that using EHRs to improve quality requires investing in additional human resources to carry out interventions. "New information creates new responsibilities" to improve quality, Calman says. For example, the EHR system tracks whether lab results and specialist reports are received when expected, which creates accountability for follow-up with patients. Similarly, the depression screening has identified many patients with possible mood disorders that require further evaluation. The costs of implementing EHR-enabled quality improvements such as these can exceed the savings from EHR-generated improvements in efficiency.

As EHRs reveal multiple areas for improvement, the challenge is to decide where to focus limited resources and attention. For example, Calman asks, would it be better to focus on patients who haven't had colorectal cancer screening, or on patients with lipid-lowering medication who haven't had a liver test? "No one knows what's more important," Calman says. "We also need to know how to incorporate interventions into everyday practice, without taking too much time during the clinical encounter."

The Institute plans to collaborate with epidemiologists and statisticians to analyze its data, using appropriate adjustments for potential confounding factors. The goal is to better understand the causes and consequences of health disparities and the effectiveness of interventions to improve quality of care, such as nutritionist counseling for diabetic patients. "We feel strongly that we have a public responsibility to examine and interpret the data correctly so that we make responsible recommendations" for change, Calman says.

Because underserved patients often face financial access barriers and medical and psychosocial challenges, "it takes enormous organizational will to do the same thing for everyone," Calman says. "It's not that difficult for doctors to treat all their patients the same." The hard part is making sure that "what the doctor orders gets done," he says. This means ensuring patients can get prescription medications and services outside the practice, such as referrals to specialty care.

From a health care perspective, Calman notes, "we enter people's lives at the late stage," when the effects of a lifetime of poverty have already taken their toll on disease development and progression. "You can't enter this late in the game and expect that doing the same things for all patients will fix it all," he says. "This would be akin to intervening in the educational system at the 11th grade and expecting equal competency at graduation."

This realization drives the Institute's engagement with local organizations to help community members make realistic behavioral changes and empower them to advocate for policy changes. Collaboration with faith-based organizations has been one of the most fruitful areas of involvement, Calman says. For example, the Institute works with church food committees to plan healthy Sunday meals and provides a monthly church bulletin insert with health information on topics such as diabetes, nutrition, and exercise. Educational strategies focus on realistic goals, such as walking 10 blocks at a good pace every day.

The operations of the network and of each practice site also make a difference in terms of ensuring equal treatment for all. For example, the Institute offers two free clinics on Saturdays that attract many uninsured patients who typically receive care through the emergency room. Because Institute physicians rotate at the free clinics, managers were concerned that these patients were not receiving continuity of care. In response, the Institute now assists patients in transferring to regular clinics after the first few visits at the free clinic, thus ensuring the same quality of care for all patients.

Implications: Organizational commitment—expressed through mission, structure, and resources—is key to achieving equity in treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. In addition to ensuring access to care, "it takes support from sophisticated information technology and a way of assuring resources to follow-up on identified problems," Calman says. Because of the complex interaction of medical and nonmedical factors affecting health, ensuring equal treatment is a necessary but insufficient step to eliminate health disparities.

Successful implementation of EHRs requires organizational readiness: openness to innovation, financial strength, and organizational stability. Leadership enthusiasm and existing information technology expertise are also beneficial.[7]

For Further Information: View the policy journal on the Institute's Web site or contact Calman at [email protected].

References

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006) Eliminating Racial & Ethnic Health Disparities; J. M. McGinnis et al. (2002) The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion. Health Affairs 21, 78–93.

[2]M. C. Beach et al. (2004) Strategies for Improving Minority Healthcare Quality. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment Number 90. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

[3] N. S. Calman (2004) Ending Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Outcomes: From Community-Based Research to Community Action. Presentation to the NIH Director's Council of Public Representatives.

[4] S.A. Kaplan et al. (2006) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health: A View from the South Bronx, Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 17, 116–127.

[5] N. Calman (2005) Making Health Equality a Reality: The Bronx Takes Action. Health Affairs 24, 491–8.

[6] N. Calman (2006) Remarks at a Congressional Briefing on Health Information Technology for Community Health Centers. Washington, DC: National Association of Community Health Centers.

[7] N. S. Calman (2004) Seven Steps to Success with Electronic Health Records. New York: Institute for Urban Family Health.