Summary: One of the most challenging aspects of building an accountable care organization (ACO) is bringing together physicians and hospitals to pursue quality-improvement and cost-reduction goals when their operations are not otherwise integrated. This case study provides an example of how a Boston-area independent practice association (IPA) forged relationships among physicians and a hospital to share in savings generated by improved quality and lower costs. The IPA built trust among its partners by demonstrating the value of investing a portion of those savings to create the infrastructure needed to achieve a common goal: better care for patients.

By Doug McCarthy

Issue: There is growing interest in using payment mechanisms to bring physicians, hospitals, and other providers together in ACOs to remedy the fragmentation, inefficiency, and suboptimal patient experiences and outcomes endemic to traditional health care arrangements (see the In Focus in this issue). The experience of physician-led entities such as IPAs that have successfully created such ACOs is likely to be of interest to physicians and others seeking ways to organize physicians for this purpose.

Organization: The Mount Auburn Cambridge Independent Practice Association (MACIPA), serving several Cambridge-area communities of metropolitan Boston, Mass., was founded in 1985 to organize local physicians into a virtually integrated group that could negotiate risk-based (capitated) managed care contracts with health plans.1 These contracts have allowed MACIPA to partner with the Cambridge-based Mount Auburn Hospital to create an infrastructure for care coordination that emphasizes innovation and new ventures with physicians to improve quality and patient care, according to Barbara Spivak, M.D., a practicing internal medicine physician and MACIPA's president.2

MACIPA's 500 physician-members encompass 55 specialties and practice in a variety of clinical settings. Most have admitting privileges at the 203-bed Mount Auburn Hospital, which shares financial risk with MACIPA in managed care contracts. About 15 percent of MACIPA's physician membership have admitting privileges at the Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA).3 Mount Auburn Hospital and CHA are regional teaching affiliates of Harvard Medical School. More than one-half of the IPA's physician-members are salaried employees of the affiliated hospitals (for example, internists, obstetrician-gynecologists, emergency medicine physicians, and hospitalists) or of specialty practices owned by the hospitals.4

The IPA's 110 primary care physicians (PCPs) typically work in family practice, internal medicine, and pediatric practices of between one and four doctors each; 10 PCPs work in a multispecialty group of 20 physicians. "We are very highly organized around our primary care doctors. Our system has for years believed that better management occurs when it's the primary care doctor who's coordinating and managing the care of the patient," says Spivak.

Governance and Staff: MACIPA is governed by a 19-member board of directors made up of 10 primary care physicians and nine specialist physicians elected by physician members to be representative of their interests and viewpoints. The board includes physicians in private practice and those employed by hospitals. Physicians also serve on committees responsible for credentialing, medical policy, finance and budgeting, information technology, and primary care leadership.

Spivak devotes about 60 percent of her time to IPA administrative duties. A staff of 42 employees includes an executive director, part-time medical director, clinical pharmacist, nurse case managers, information specialists, and quality improvement professionals, among others. Administrative offices are located in Brighton, Mass.

Population Served: MACIPA serves a defined population of 51,000 health plan members who have selected a participating physician as their PCP, including 40,000 under risk-based contracts and 11,000 under fee-based contracts.

The risk-based contracts cover 36,400 individuals enrolled in commercial health maintenance organizations (HMOs) offered by Tufts Health Plan, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care; 3,600 seniors are enrolled in Tufts' Medicare Advantage plan.

Managed care patients covered under MACIPA's risk-based contracts account for 20 percent of Mount Auburn Hospital's inpatients and for 50 to 70 percent of a participating PCP's total patient volume, depending on the patient demographics of the practice and whether the PCP participates in the Medicare Advantage plan.5 Physician-members may see other patients who are covered by traditional (fee-for-service) health insurance plans.

Contracting and Budgeting: In 1985, MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital jointly entered into a risk-based contract with Tufts Health Plan, typical of that plan's contracting arrangement with providers.6 By the mid-1990s, MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital had negotiated capitation contracts with the other two major health plans in the region (mentioned above). Under the commercial health plan contracts, MACIPA and Mount Auburn are responsible for the complete cost of patients' care, including inpatient, outpatient, physician, pharmacy, home health, and skilled nursing care. PCPs participating in the Medicare Advantage Plan bear the financial risk for that contract.

Groups seeking to become an ACO "need to understand and have a reasonable financial package" that includes a medical expense budget and an overhead component to fund a care management infrastructure, Spivak says.

MACIPA and Mount Auburn determine, and negotiate with the health plans to agree on, an adequate capitation budget needed to care for patients based on a combination of factors: 1) previous cost and utilization experience applied to the demographics (age and gender) and health conditions of the patient population (using a risk-adjustment methodology called diagnostic care groups), 2) projected cost trends, and 3) estimated cost savings to be achieved from care management activities. The IPA and hospital maintain reinsurance that assumes payment for catastrophic cases reaching a high-dollar (stop-loss) threshold.7

The IPA and hospital also must account for the cost of care when patients are referred or request to use a hospital outside their system, such as one of the academic medical centers (AMCs) in Boston. Because the cost of care is typically much higher at the AMCs, this arrangement creates a powerful incentive for MACIPA and the hospital to create a local care system capable of delivering superior care to meet most needs of the patient population.8

"Over the past 12 years, we've moved substantially ahead in many clinical programs and clinical areas in order to justify asking the patients to stay here at the home hospital," says Jeanette Clough, president and CEO of Mount Auburn Hospital. "We have a very unique culture here of managing together, leading together, and working together" with established referral relationships supported by a common electronic record system, she notes.

The IPA's physician-members and their affiliated hospitals bill the responsible health plan for services as they are rendered, and the health plan then reimburses providers from the capitation budget at contracted rates. The IPA withholds a proportion of physician fees as a risk-sharing mechanism, but it has consistently returned 100 percent of this fee withhold to member physicians at the end of each year.

At the end of the contract year, MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital reconcile their financial responsibility for actual medical expenses against their respective share of the capitation budget. If expenses exceed the budget for a particular contract, the IPA pays the deficit out of surplus from other contracts, if available, or from risk reserves set aside from prior surpluses for this purpose.9 If there is a surplus across all contracts (after the return of the fee withhold), the IPA distributes it to its member physicians (including hospital-employed physicians) based on an IPA-developed formula, with 15 percent of a physician's share dependent on his or her participation in IPA activities and achievement of quality goals.

In 2009, MACIPA became the first group in the state to sign an innovative "Alternative Quality Contract" with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, which incorporates: 1) declining annual increases in global payment (adjusted for patient health status) to encourage efficiency gains over the five-year contract, and 2) performance incentives worth up to 10 percent of the global budget for meeting inpatient and ambulatory quality and outcome goals.

While establishing a reasonable capitation budget is important, success doesn't depend solely on skillful contract negotiations with the health plan but equally on careful monitoring and management and real-time intervention. "Even if your budget or your reinsurance is a little off, you can stay on top of costs on a day-to-day basis if you manage the care well," Clough observes.

Care Management: "To save money on the health care expense side you have to have a significant amount of infrastructure dollars to support a team that will help keep costs down," Spivak says. MACIPA's capabilities have evolved over the years and currently include a high-risk case management program for patients at Mount Auburn Hospital and in the community, discharge planning, pharmacy management, referral management, utilization review, and related information services including performance reporting to physicians on utilization and quality improvement. Health plans delegate authority to the IPA to take responsibility for these care management activities, although the plans retain some activities as a form of shared responsibility.10

The IPA's pharmacy management program, for example, combines two components: 1) education conducted by a clinical pharmacist and a physician advisor to help doctors choose the most appropriate drugs for treating particular conditions, and 2) polypharmacy review by the clinical pharmacist to identify potentially unsafe drug combinations among patients taking eight or more drugs, as well as opportunities for generic substitution to reduce pharmacy costs and patient copayments. To illustrate the value of this resource, Spivak describes a patient who was unable to reduce a high cholesterol level on standard drug therapy but succeeded in doing so after the clinical pharmacist helped devise an alternative treatment strategy.

In the case management program, patients are stratified based on their risk of poor outcomes as identified by their physician, a review of clinical data, or at hospital discharge. Patients at highest risk, such as those with severe chronic conditions such as congestive heart failure or uncontrolled diabetes, may receive home visits by a nurse practitioner (NP), under contract to the IPA, who provides intensive patient and family education, supports medication adherence, and helps prevent hospital admissions or readmissions. NPs also visit patients undergoing rehabilitation in skilled nursing units to help them make a timely and successful recovery, which can reduce a typical three-week length of stay to 12 to 14 days, depending on the patient's condition. (Using NPs rather than visiting nurses for this job allows for more timely care, since NPs can make medical decisions "on the spot" within the scope of their licenses.) Patients with less severe conditions or who make improvement receive periodic calls from nurse case managers employed by the IPA.

Information Technology: The IPA and Mount Auburn Hospital made a time-limited promise of financial and technical assistance to encourage participating physicians to adopt a common electronic health record (EHR) system that interconnects with the hospital's clinical information system to share laboratory and radiology results. About 85 percent of the PCPs have done so since 2006, when the first physicians went "live" on the new system, and Spivak expects that 75 percent of the IPA's specialists will have done so by year end. (Cambridge Health Alliance physicians use a different EHR system.)

The joint financial support pays for the EHR software license, training, a central data center, and communications lines. Some of the health plans also designated a portion of the capitation dollar for this purpose. Physicians are responsible for purchasing hardware and for an ongoing discounted maintenance fee. They also must absorb the cost of lost productivity while implementing the system. The IPA is working with the Massachusetts eHealth Institute to help eligible doctors obtain funding under the federal HITECH Act.

"We believe we've made the case, and a good case, that going on the electronic health record will in the long run—and I think you have to underline 'in the long run'—help us to provide better care to our patients and will allow us to communicate more effectively with each other," Spivak says.

Communication and Teamwork: Primary care physicians are clustered into "pods" of about eight PCPs each for purposes of communication. Each month, one physician from the pod is designated to attend an IPA educational meeting led by a peer on a current topic such as a new clinical protocol, the effective use of a new drug, or appropriate test ordering. The physician then shares this learning with his or her colleagues in the pod during a separate monthly meeting. Case managers also attend to discuss difficult cases with the primary care team. At the meeting, each doctor receives a list of his or her patients who are in hospice, home care, rehabilitation, or similar programs so that they are aware of the patient's current status in the system.

The IPA has learned that this kind of topical approach is more effective in getting physicians' attention and engagement than simply providing them with a static performance report each month, according to Spivak. Topics of concern are often suggested by the IPA's specialists, or through a review of claims data. For example, if the IPA determines that doctors are overusing myocardial perfusion imaging stress tests, it gives doctors data showing how their test ordering compares with colleagues, along with an educational session conducted by a cardiologist to describe, "Here's how you should be ordering it and when," says Spivak. The IPA will then monitor to see if the education had the desired impact.

Participating physician practices also contribute to care management and improvement activities as a shared responsibility. For example, the IPA's quality improvement department uses disease registries to track patients with chronic conditions and provides periodic updates to PCPs on their patients in need of preventive or follow-up care. Specialists are asked to conduct a quality improvement project, and to report on their progress at year end. For example, an obstetrics group is working on improving patient safety by ensuring that patients received clear instructions for care following a procedure. These activities are used to determine a physician's eligibility for sharing in any year-end financial surplus.

Clough sees this responsibility for quality carrying over into the hospital, whether in easing the implementation of a computerized physician order-entry system (which physicians have resisted in some hospitals) or by working on improving inpatient quality metrics. "Physicians have had a tradition here of stepping up and they've created a marvelous infrastructure. We've helped with that, but they've really put it together themselves" she says.

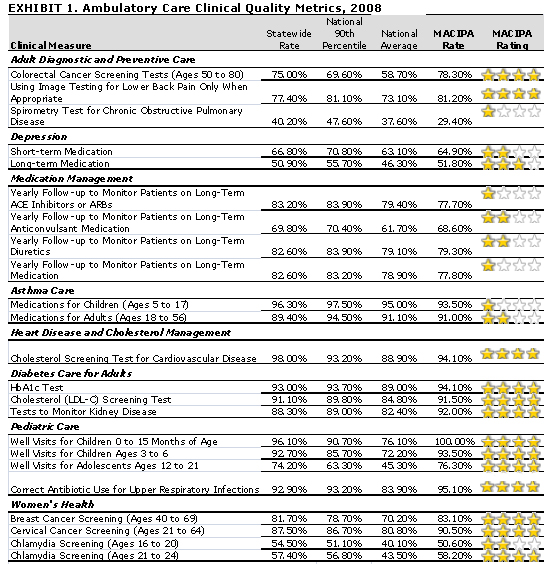

Results: Physicians in the IPA have achieved notable results on 12 of 23 measures of ambulatory care quality on which they were rated by the Massachusetts Health Quality Partners [www.mhqp.org] (MHQP), exceeding both state and national benchmarks for the care of diabetic adults, preventive care for children and adults, and appropriate use of imaging tests for lower back pain (Exhibit 1). These represent areas of focus for the IPA's quality improvement efforts. Overall, MACIPA achieved about 74 percent of possible clinical star rankings, with opportunities for improvement in several areas.11 For example, the IPA is currently working on improving depression care through peer education, conducted by a psychiatrist, to help improve medication management and adherence.

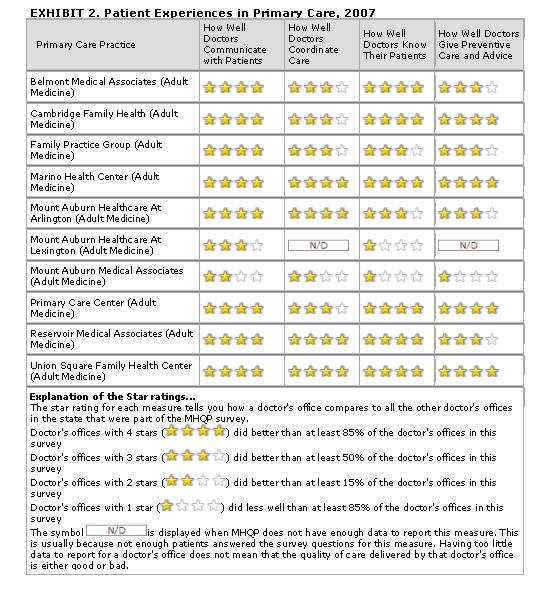

Among 10 MACIPA primary care practices rated on a 2007 MHQP statewide survey of patient experiences with care, eight exceeded the state average on all four dimensions measured (at least three stars), and seven practices exceeded the 85th percentile of performance (that is, they ranked in the top 15 percent of practices) on two or more dimensions (four stars) (Exhibit 2).

On hospital quality indicators reported by the federal government, Mount Auburn Hospital's performance exceeds the average for the U.S., the state, teaching hospitals, and the Boston hospital referral region for evidence-based treatment of heart attack, pneumonia, and heart failure, prevention of surgical complications, and for patients' overall rating of their hospital stay and whether they would recommend the hospital to friends and family.12

Among Medicare Advantage patients treated at Mount Auburn Hospital, the 30-day readmission rate (to any acute-care hospital) is in the range of 12 to 14 percent, compared with almost 20 percent nationally.13 The IPA has set a goal to reduce readmissions to under 10 percent by 2011 through efforts such as increasing the timeliness of follow-up care after hospital discharge, through an appointment with a PCP, visit by the NP in the home, or call by a care manager.

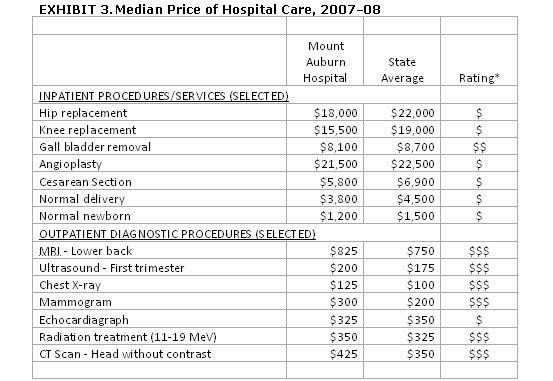

Data compiled by the Massachusetts Health Care Quality and Cost Council show that the median price of selected inpatient procedures and services provided at Mount Auburn Hospital is generally below the median price for hospitals in the state of Massachusetts, while the median price of selected outpatient diagnostic procedures is generally higher than the statewide median price (Exhibit 3). A recent analysis of these data among Boston-area hospitals reported that Mount Auburn's prices were substantially lower than those at the most expensive Boston academic medical centers, but were higher than at many of the area's community hospitals.14 Since 1998, the hospital has engineered a turnaround in its financial performance, achieving consistent profitability and surviving a shake-out in the market that saw the shuttering of several neighboring community hospitals.

Under the Alternative Quality Contract with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital (as well as other participating groups) have achieved about twice the rate of improvement on a broad set of ambulatory care quality measures as providers that do not participate in the contract, according to Dana Gelb Safran, Sc.D., the insurer's senior vice president for performance measurement and improvement (see the accompanying interview with Safran for more on this topic). MACIPA has consistently performed well above average and is "one of our better-performing groups" participating in Tufts Health Plan's Medicare Preferred product, according to Jonathan Harding, medical director for senior products.15

| Explanation of the Star Ratings...

The three benchmarks used for comparison are:

Source: Massachusetts Health Quality Partners, www.mhqp.org. |

| Source: Massachusetts Health Quality Partners, www.mhqp.org . |

| Source: Massachusetts Health Care Quality and Cost Council, http://archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/46754 Data represent the time period July 2007 to June 2008 (claims paid through December 2009). *Legend $=Below Median State Cost. $$=Not Different from Median State Cost. $$$=Above Median State Cost. |

Lessons Learned: Reflecting on the experience of the IPA, Spivak notes the importance of a respectful approach. "Neither the physicians nor the hospitals like to be told what to do and how to do it. Doctors in particular are used to doing everything on their own. And the reality is that when you're starting an ACO you have to deal with people's anger and disappointment that the world is changing. And I believe the way to do that is to develop a team that's going to help them do what they want, which is give better care to their patients."

Working with physicians to improve care in turn requires demonstrating how the IPA adds value through data and systems that help them provide the best possible care. "It isn't just enough to say you're ordering too many tests. You have to say, "This test should be ordered in this way, and here's your data, and here's an example of a patient who would have been treated differently," Spivak notes. "Every group I know wants to be proud of the job that they're doing. By giving people data on where they're not doing as good a job as they could, and by helping their patients stay out of the hospital, that helps them deliver better care."

From the vantage point of a hospital CEO, Clough sees the opportunity for physicians to exercise leadership in both clinical and financial decisions as the key to the shared-risk model's success. "They are masters of their own destiny. That puts them in the driver's seat for the way the dollars get spent. It puts them in control of quality. They're at the negotiating table with us; they're not dependent on us to negotiate for them. Because the hospital is comfortable with the physicians being in charge, they're in a much better position to point out needs that the hospital has, whether for capital, services, or recruitment." For example, Clough consults with the IPA when recruiting hospital-based specialists to make sure the candidate will be a good fit for both the hospital and the IPA. "It's very symbiotic in terms of the way that we work together," she says.

The IPA has built a strong working partnership with Mount Auburn Hospital based on a common belief in the value of primary care and a shared incentive to retain the loyalty of patients. "The hospital and the IPA have similar interests in providing high-quality care, even if costs a little more upfront to develop the systems to do so," Spivak says. This philosophical congruence leads the hospital and the IPA to make mutually beneficial investments in inpatient and ambulatory care, respectively. "That consistency [in approach] allows us to work better together and to contract better together." The hospital and the IPA also work hard to identify complementary approaches that maximize their respective strengths and avoid duplicating their systems.

"The whole model is built around the PCP as the pivotal focus of managing the patient's care," says Clough. "And that's something that we all really believe is key to managing the cost and the quality of care. The hospital is interested in that for a couple of reasons: 1) It integrates the physicians with the hospital and integrates their patients with the hospital so that we can work together to be more efficient, and 2) the opportunity to earn additional dollars if we can manage within the budgets that have been provided."

Clough is a strong believer in the risk-based contracting arrangement with the IPA. "It has been a long-term strategy on the part of the hospital as well as the IPA that we've chosen to sustain despite many challenges in the environment" that led others to drop the approach, she says. While the hospital and the IPA remain separate legal entities, common understanding is facilitated at the governance level since the hospital board includes community physicians who are members of the IPA, and the IPA board includes hospital-employed physicians.

"We both believe that we are in this together, we are risk partners, and that if one of us fails, we both fail. Every contract has to be a win-win for both of us," Spivak says. "If the physicians are going to succeed, they need to have a hospital that will benefit and work with them to improve utilization, efficiency, effectiveness, and quality. And for the hospital to succeed, they need to be invested in having physicians that are going to want to send their patients there." Clough concurs. "When you're at risk with somebody, you try to figure out without any questions asked how to make them successful. The incentives are so aligned that our success is literally their success and vice versa," she says.

Safran, at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts, believes that the partnership between the hospital and the IPA has allowed them to make significant gains in integrating care—functioning as a true health care system. "For example, under a traditional contract, hospitals have had no incentive to figure out ways to avoid admitting patients who show up at the ED and could be well managed without an admission if the ED were able to reconnect the patient to their community-based doctors. MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital’s relationship exemplifies the best of creative and effective approaches to functioning as a true system.” Illustrating this partnership, Safran notes that the hospital has created a process to notify PCPs when their patients visit the ED, and to provide PCPs with timely laboratory test results that are pending at the time of hospital discharge so as to facilitate appropriate follow-up care and avoid unnecessary readmissions. “That may sound obvious, but it’s often not happening” in typical fee-for-service care arrangements, she says.

Both Spivak and Clough are quick to acknowledge that this alignment doesn't preclude conflict, but it does provide an overarching incentive to work out disagreements to the mutual success of both parties. For example, when Mount Auburn Hospital was experiencing financial losses in the late 1990s, it renegotiated the terms of the risk-sharing arrangement with the IPA to share in more of the savings in return for a greater share of the risk.16 "There are occasionally things we disagree about, but those are actually fairly few, and they never get in the way of making progress together," Clough says.

While MACIPA does not have the shared incentives and volume of patients in the Cambridge Health Alliance (CHA) hospitals, their inclusion in the system facilitates cooperation between the affiliated physician groups that helps keep care local. For example, patients who need cardiac procedures not offered at CHA hospitals can have them done at Mount Auburn Hospital, which can be more convenient and less expensive than traveling to one of the AMCs downtown, Spivak says. The new Alternative Quality Contract with Blue Cross Blue Shield creates an overall financial incentive in the capitation budget for MACIPA to work more closely with CHA hospitals to effectively manage care.

Going forward into an environment of constrained resources, Spivak notes that it will become increasingly difficult to find savings as MACIPA has already achieved many of the early gains made possible by implementing systems and programs. She sees opportunities in two related areas: 1) developing innovative ways to help patients to do a better job of managing their health and care through better benefit design and more effective motivational coaching by their providers, and 2) improving primary care access to help decrease unnecessary use of the hospital emergency department.

Implications: Two characteristics of MACIPA's care management programs distinguish them from typical managed care approaches of the past. First, they exhibit a preference for local staffing and implementation rather than arms-length or third-party contact (though the IPA may use vendors and information products to assist in its work). Second, they focus on building partnerships with physicians and patients through the use of timely education and tailored intervention rather than the use of repetitious reports or mandates. Capitated payment and delegated medical management means that contracted provider groups view health plan members as "their own" and puts doctors in charge of deciding how to reduce the burden of disease and its associated costs, says Harding at Tufts Health Plan.

MACIPA's experience demonstrates that it is possible to create a physician-led ACO that finds common ground with a hospital when they have a joint interest in preserving and expanding their patient base by providing better care. This in turn requires that physicians prepare to take a leadership role and that hospital administrators partner with them to do so. It also requires a willingness to invest resources in building a shared local infrastructure for data analysis, care management, and quality improvement. MACIPA's experience is most likely to be relevant to other urban areas characterized by competition for patients among hospitals and other providers.

For Further Information: Contact Barbara Spivak, M.D., at [email protected]. A video of Dr. Spivak discussing MACIPA's experience with capitation payment is available on the Massachusetts Medical Society Web site.

Notes

1 The IPA's primary competitors in the region are hospitals and affiliated physicians in the Partners Healthcare and Caritas Christi Health Care systems.

2 Testimony by Barbara Spivak, M.D., "Making Health Care Work for American Families: The Role of Public Health," House Energy and Commerce Committee, Subcommittee on Health, March 31, 2009.

3CHA is paid as a vendor by MACIPA and does not share risk under its managed care contracts.

4 Hospital-employed physicians are on an equal footing with independent physicians in the IPA: both sign a contract to participate in the IPA; the hospital or practice also signs the IPA contract as the responsible financial party.

5About three-quarters of MACIPA's PCPs participate in the Tufts Medicare Advantage plan, which contracts with them by subgroups known as pods.

6 HealthLeaders-InterStudy, 2010 Market Overview: Boston (Decision Resources, Inc., Feb. 2010).

7 Spivak notes that the reinsurance mechanism does not help in situations such as the recent H1N1 flu epidemic that led to many unexpected episodes of care below the stop-loss threshold.

8 MACIPA patients are referred to centers of excellence for the treatment of complex conditions for which the local system lacks expertise, such as transplantation, rare cancers, or severe burns. MACIPA also may determine that a referral outside the system is appropriate when a patient has a preexisting relationship with a specialist outside the system.

9 Since they began joint-risk contracting, MACIPA and Mount Auburn Hospital have not had an overall deficit across all contracts.

10 For example, Tufts Medicare Advantage plan administers centralized disease management programs for patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on behalf of its contracted provider groups.

11 The IPA believes that reported medication management measures do not reflect actual performance because of limitations in claims data coding. The IPA does not focus on some measures, such as spirometry for COPD, that it has determined are not useful for improving treatment.

12 Data were downloaded in June 2010 from www.whynotthebest.org.

13 S. F. Jencks, M. V. Williams, and E. A. Coleman, "Rehospitalizations Among Patients in the Medicare Fee-for-Service Program," New England Journal of Medicine, 2009 360(14):1418–28.

14 M. Bebinger, "Mission Not Yet Accomplished? Massachusetts Contemplates Major Moves on Cost Containment," Health Affairs 2009, 28(5):1373–81.

15 Tufts Medicare Preferred ranks consistently among the top 10 Medicare Advantage Plans in the country based on quality and member satisfaction scores, according to U.S. News and World Report.

16 L. M. Roberts and A. Kanji, Jeanette Clough at Mount Auburn Hospital, Harvard Business School Case 9-406-068, Dec. 2006.

This study was based on publicly available information and self-reported data provided by the case study institution(s). The Commonwealth Fund is not an accreditor of health care organizations or systems, and the inclusion of an institution in the Fund’s case studies series is not an endorsement by the Fund for receipt of health care from the institution.

The aim of Commonwealth Fund–sponsored case studies of this type is to identify institutions that have achieved results indicating high performance in a particular area of interest, have undertaken innovations designed to reach higher performance, or exemplify attributes that can foster high performance. The studies are intended to enable other institutions to draw lessons from the studied institutions’ experience that will be helpful in their own efforts to become high performers. It is important to note, however, that even the best-performing organizations may fall short in some areas; doing well in one dimension of quality does not necessarily mean that the same level of quality will be achieved in other dimensions. Similarly, performance may vary from one year to the next. Thus, it is critical to adopt systematic approaches for improving quality and preventing harm to patients and staff.