Summary: An innovative project in New Mexico uses telemedicine, case-based learning, and disease management techniques to expand access to care for patients with hepatitis C and other chronic, complex conditions. Specialty providers based at the University of New Mexico help guide rural community providers in applying best practices to manage care. The community providers build their knowledge of particular conditions and serve as expert consultants in their regions.

By Martha Hostetter

Issue: Because of severe shortages of specialty providers in rural areas, people with complex conditions such as hepatitis C or rheumatoid arthritis often have to travel long distances or wait months to get treatment. Such problems are compounded by the fact that many rural patients are poor and/or uninsured. Given these barriers, such patients often forgo treatment or wait until they have severe complications before seeking help.

New Mexico has a high proportion of residents who are poor (19.3 percent vs. 13.2 percent nationally) and uninsured (23.2 percent vs. 15.4 percent across the nation). And while more than one-third of residents live in rural or frontier areas, only 20 percent of the state's physicians practice there.

Objective: Project Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (Project ECHO) is designed to enhance the capacity of community health care providers to safely and effectively treat chronic, complex diseases such as hepatitis C in New Mexico's rural and medically underserved communities.

Organization and Leadership: Project ECHO is based at the Health Sciences Center at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, the state's only academic health center, in Albuquerque. Sanjeev Arora, M.D., professor of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology) at the Health Sciences Center, is the director and principal investigator of Project ECHO. Participating community providers treat patients in the state's prisons, federally qualified health clinics, rural family practice residency programs, Indian Health Service clinics, and primary care practices.

Project ECHO began in 2004 with $1.5 million in funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and matching funds provided by the state. Since 2006, the New Mexico Legislature and the Department of Health have provided annual funding of $1.6 million.

Target Populaton: Project ECHO providers treat patients in the following areas:

• asthma;

• child, adolescent, and family psychiatry;

• chronic pain;

• diabetes/cardiovascular risk reduction;

• hepatitis C;

• high-risk pregnancy;

• HIV/AIDS;

• integrated addiction/psychiatry;

• medical ethics;

• occupational medicine;

• pediatric obesity;

• psychotherapy; and

• rheumatology.

These clinical conditions are targeted because they are common, require complex treatment, and have a significant impact in terms of health and economic consequences. In addition, disease management for these conditions has been shown to produce good outcomes.

This case study focuses on Project ECHO's work with hepatitis C patients. In 2004, approximately 28,000 New Mexico residents had contracted the virus, yet less than 5 percent of them had been treated. In addition, thousands of prisoners had tested positive for the disease (with many more suspected of having it), but none had been treated. Lack of treatment can lead to severe complications, cirrhosis, or death. New Mexico has the highest rate of deaths from chronic liver disease or cirrhosis in the nation—linked both to hepatitis C and alcohol abuse.

Hepatitis C is curable in from 45 to 80 percent of cases, but treatment entails an intricate drug regimen and management of potentially severe side effects. Since many hepatitis C patients have psychiatric and substance abuse problems, effective treatment also requires patient education and behavioral changes.

Timeline: Project ECHO was launched in 2004. In all, there are 255 treatment sites around the state, including 21 focusing on hepatitis C.

Process: Project ECHO is based on four platforms:

• the use of teleconferencing and videoconferencing;

• case-based learning;

• disease management, focused on evidence-based care protocols; and

• use of a Web-based disease management tool to track outcomes.

Providers are recruited to participate in Project ECHO through presentations and the networks of partner organizations. At each of the 21 hepatitis C community practices, participants include a lead clinician (a physician, nurse practitioner, or physician assistant) as well as nurses or medical assistants who help manage patients' care. None of these sites had treated hepatitis C patients before joining.

Project ECHO is free and providers can earn continuing medical education credits for their participation. When a new provider joins, a team visits their practice to conduct a training workshop and assist with installation of technology for data sharing and audio/video conferencing. In addition, community providers visit the University of New Mexico to shadow clinicians as they treat hepatitis C patients.

Community providers take part in weekly hepatitis C clinics, called "Knowledge Networks," by joining a videoconference or calling into a teleconference line. There are two hepatitis C clinics each week: one for rural providers and one for those who treat prisoners, who tend to have high rates of recent substance abuse and psychiatric illness and therefore have different treatment protocols than other patients. The providers take turns presenting their cases by sharing patient medical histories, lab results, and treatment plans. University of New Mexico specialists from the fields of gastroenterology and hepatology, infectious disease, psychiatry, pharmacology, and substance abuse listen to the case histories, ask questions, and provide advice. Project ECHO pays these specialists by reimbursing their university departments for the time they spend on such consultations.

Working together, the community providers and specialists manage patients' care following evidence-based protocols. (Community providers are ultimately accountable for patients' care, with specialists serving as consultants.) A major decision point is whether to initiate treatment—a process that can last as long as 18 months—or to first encourage behavioral changes that can improve outcomes such as weight loss or alcohol cessation. Discussion also centers on medication regimens, the best ways to handle the side effects of treatment, and issues related to psychiatric conditions or substance abuse.

According to Arora, this case-based approach creates a "learning loop," with community providers comparing notes, taking part in shared decision making, and learning from each other as much as the experts. It is effective, he says, because providers learn by "doing" rather than by reading medical literature or attending conferences. Community providers attend biweekly lectures (via video or teleconference) on clinical issues such as vaccination for hepatitis A and B and diagnosis of depression.

Using an electronic disease management tool, specialists at the University of New Mexico monitor the treatment process and outcomes. This oversight helps to ensure that community providers are following evidence-based care protocols. When needed, the specialists recommend mid-course corrections. For example, if a patient's lab test results suggest he is not complying with prescribed interferon injections, they might suggest to his community provider that the patient come into their office for weekly injections. Remote monitoring of care gives Project ECHO's leaders insights into the way the care protocols play out in busy clinics, enabling them to make improvements.

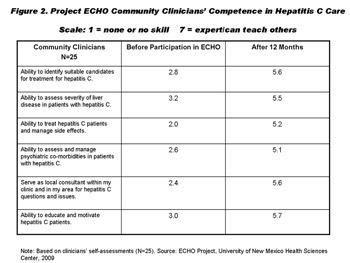

Planners follow a regional strategy, seeding expertise in particular clinical areas throughout the state (Figure 1). Primary care providers teach disease management skills to their coworkers and serve as expert consultants for their peers in the region. The goal is for care teams at the community clinics to learn to work together to manage chronic conditions, so that primary care providers gain competence in identifying and treating high-risk hepatitis patients while nurses and other office staff become adept in patient education and support.

Figure 1. Map of Project ECHO Treatment Sites

Source: ECHO Project, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, 2009

"We don't want every doctor in every part of the state to be an expert on hepatitis C," says Arora. "We want to create centers of excellence throughout the state."

Key Measures: To gauge the effectiveness of this care delivery model, leaders track the following measures:

• participating community providers' self-reported knowledge and skills of hepatitis C care; and

• quality and safety of care, as assessed through health outcomes.

Results: Project ECHO has expanded access to care for hepatitis C patients who otherwise would not have received treatment. Since 2004, there have been 400 Knowledge Network clinics, through which some 50 rural and prison-based clinicians have received more than 4,000 consultations on hepatitis C patients. The clinicians have earned a total of 5,100 continuing medical education/continuing education hours. Through this process, 21 community or prison-based clinics have become "centers of excellence" in hepatitis C care.

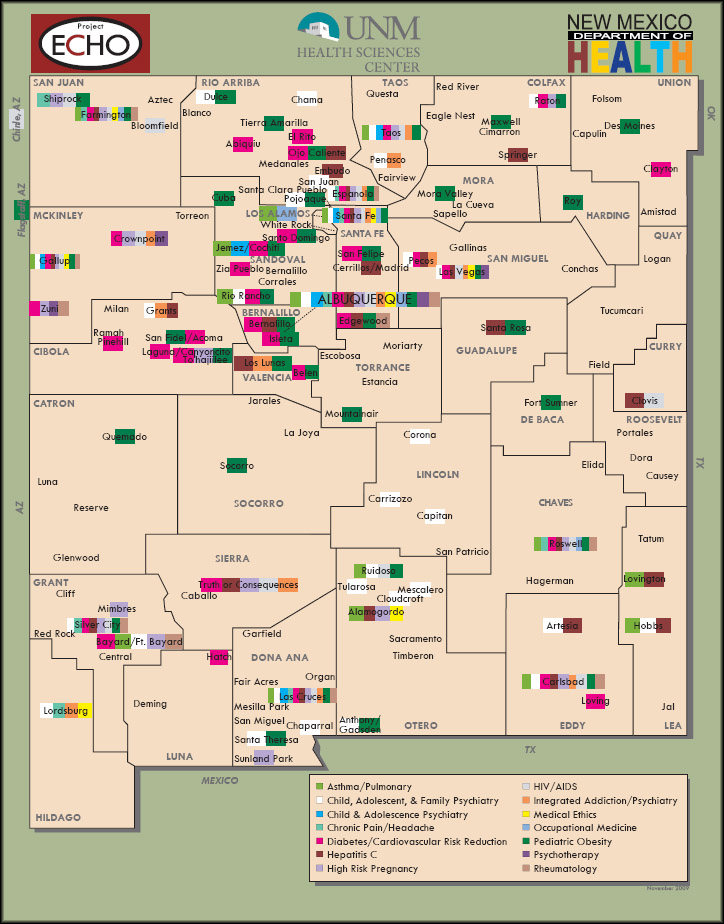

After participating in ECHO for 12 months, community providers (physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) complete surveys evaluating the program. On all measures, providers reported having greater knowledge of and confidence in treating hepatitis C patients after participation (Figure 2). Notably, their self-reported ability to serve as local consultants for hepatitis C improved significantly. ECHO's leaders have used the results to improve the program, for example adding lectures on topics such as drug interactions and substance abuse.

Although these results are from a self-selected group of volunteers, such motivated individuals are what the program needs to succeed. "This is not for everyone," Arora says. "Many primary care physicians think diseases like hepatitis C are specialist diseases—not part of their job. But some have a desire for greater specialized knowledge and feel committed to help underserved patients who can't come to the city for care."

In another survey, community clinicians reported that Project ECHO reduced their sense of isolation and improved their professional satisfaction.

From 2005 to 2009, Arora and his colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study to compare the quality and safety of hepatitis C care delivered by University of New Mexico specialists with that delivered by ECHO-trained community providers. The intervention sites were 14 community clinics and seven prison sites, at which providers treated a total of 257 patients. The University of New Mexico Liver Clinic served as the control site, with 127 patients.

The researchers found that rural and prison-based primary care clinicians delivered care that was as safe and effective as that delivered in the university hepatitis C clinic (Figure 3). There were no significant differences between the rates of patients who were cured or who did not respond to treatment. The rate of major side effects related to treatment was significantly lower among the ECHO population than among patients treated at the university clinic—a difference Arora attributes to the fact that many of ECHO's prisoner patients were large, strong men who are less likely to suffer side effects. Notably, community providers achieved cures for 57.4 percent of their patients. Other studies of community-based hepatitis C treatment found cure rates that were significantly lower.1

Next Steps: As part of their participation in Project ECHO, community providers use a customized electronic disease management tool to collect and report patient data to specialists at the University of New Mexico. Project leaders are now developing a more sophisticated electronic system that will help providers manage care through the use of physician order entry and decision support, automated prompts, and other tools. For example, if a patient's hemoglobin level falls more than 2 grams per deciliter, the system will alert their community clinician and ask whether she wants to lower the dose of Ribavirin, one of the anti-viral drugs used in hepatitis C treatment. It also will include a patient portal, so that patients can track the results of blood tests to assess the progress of their treatment.

In addition, Project ECHO recently launched a program to use the Knowledge Network model to train community health workers throughout the state. There is evidence that community health workers can play key roles in helping patients manage chronic conditions, make recommended behavioral changes, and adhere to treatment plans. Project ECHO will seek health professionals as well as laypeople to assist patients in managing diabetes, hypertension, substance abuse, and other conditions, in addition to hepatitis C.

In 2007, Project ECHO won an international "changemaker" competition sponsored by the Ashoka Foundation and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in which it was designated as a "Disruptive Innovation" that has the potential to "change health care nationally and globally." This recognition led to a $5 million award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation in 2009. These funds will be used to expand Project ECHO's work in New Mexico in six clinical areas (asthma, diabetes, substance use disorders, rheumatology, chronic pain, and high-risk pregnancy) and to replicate the model of treatment for hepatitis C patients in Washington State.

Implications: Project ECHO demonstrates that care delivered by primary care providers in rural areas and prisons can be as safe and effective as that provided by specialists in academic health centers. The goal of the project is for community providers to gain enough knowledge of hepatitis C care to become self-sufficient, though they can continue to access the Knowledge Network clinics as needed. According to Arora, providers need less and less support over time, using the clinics mainly to elicit help with complex cases. In addition, the clinics and lectures inform them of the latest research findings.

The project also demonstrates that technology and cross-disciplinary collaboration can be used to leverage scarce health care resources. Many telemedicine projects link specialists with remotely located patients. Project ECHO, by contrast, uses technology to build knowledge and skills among remotely located providers.

In addition to technology, Project ECHO relies on cross-disciplinary collaboration for chronic disease management. Collaboration among specialty and primary care providers is an inexpensive way to increase the capacity to provide complex chronic care in medically underserved communities. "There are certain diseases that get put in the basket of 'specialty diseases'—rheumatoid arthritis, hepatitis C—but in some areas there will never be enough specialists to treat them," says Arora. "How then do you get the primary care physician to do it? ECHO uses existing community clinicians and gives them the expertise and confidence to be able to treat these diseases. This results in a major expansion in capacity."

Such networks also can help alleviate the sense of professional isolation experienced by many rural providers and help them keep up to date with evolving treatment methods.

Research has shown that communication between the primary care providers and specialists is often poor: primary care providers may not receive feedback about patients they have referred, and specialists may not know the history of patients that have been sent. Project ECHO is one model of care coordination, with primary and specialty care providers working together to care for patients using tools such as videoconferences and shared electronic records.

Because Project ECHO takes a regional approach—seeding expertise in particular clinical areas throughout New Mexico—it may reduce variation and promote evidence-based, reliable care in rural areas, where patients do not have much choice when it comes to selecting their primary or specialty providers.

Other states and even other parts of the world are launching initiatives modeled after Project ECHO. In addition to the hepatitis C program for rural residents Washington state, India is launching a Project ECHO HIV/AIDS program. According to Arora, the care delivery model is not uniquely suited to rural areas, but could work in poor urban areas or any other community where there are shortages of health care providers.

To expand this model of care delivery, academic health centers will need financial incentives to help train the primary care workforce to manage chronic conditions. Today, academic health centers focus on research, training, and tertiary care. Federal and state governments could provide funds to encourage academic health centers to take on an additional mission of helping to build capacity among primary care providers to treat complex, chronic conditions. This could expand access to care—without requiring additional providers or extensive retraining.

That may be easier if the cost effectiveness of such programs, compared with traditional specialty care, can be demonstrated. Project ECHO leaders are now partnering with researchers at the University of New Mexico Bureau of Business and Economic Research to assess the economic impact of the ECHO model of care delivery.

For More Information, please contact Sanjeev Arora, M.D., [email protected].

Note

1. L. I. Backus, D. B. Boothroyd, B. R. Phillips et al., Predictors of Response of U.S. Veterans to Treatment for the Hepatitis C Virus, Hepatology, July 2007 46(1):37–47. This study evaluated the results of treatment of 5,955 patients with hepatitis C in the entire VA system and found that 1,551 were cured, with a cure rate of 26 percent; I. M. Jacobson, R. S. Brown, Jr., B. Freilich et al., Peginterferon Alfa-2b and Weight-Based or Flat-Dose Ribavirin in Chronic Hepatitis C Patients: A Randomized Trial, Hepatology, October 2007 46(4):971–81. In this study of more than 5,000 patients treated in a community setting, the overall cure rate was 44.4 percent in one arm of the study and 40.5 percent in the other.

This study was based on publicly available information and self-reported data provided by the case study institution(s). The Commonwealth Fund is not an accreditor of health care organizations or systems, and the inclusion of an institution in the Fund's case studies series is not an endorsement by the Fund for receipt of health care from the

institution.

The aim of Commonwealth Fund–sponsored case studies of this type is to identify institutions that have achieved results indicating high performance in a particular area of interest, have undertaken innovations designed to reach higher performance, or exemplify attributes that can foster high performance. The studies are intended to enable other institutions to draw lessons from the studied institutions' experience that will be helpful in their own efforts to become high performers. It is important to note, however, that even the best-performing organizations may fall short in some areas; doing well in one dimension of quality does not necessarily mean that the same level of quality will be achieved in other dimensions. Similarly, performance may vary from one year to the next. Thus, it is critical to adopt systematic approaches for improving quality and preventing harm to patients and staff.