The Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA), signed into law February 4, 2009, was a milestone in the development of quality measurement and improvement in publicly financed health care for children. CHIPRA called for new measures of child health care quality (both the adoption of an initial set of measures and an ongoing program to enhance them), quality improvement and information technology demonstration grants, new requirements for state public reporting on child health quality, development of a model electronic health record format for children enrolled in the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and Medicaid, and a variety of other provisions.

This issue of States in Action looks at progress in implementing these provisions and further opportunities for states a year after CHIPRA's enactment. Highlights include:

- In September 2009, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) awarded $40 million in grants to 69 state agencies, safety net health care organizations, and community-based organizations to expand and test innovations in use of outreach workers to enroll families in CHIP and Medicaid, technologies to streamline enrollment, and integration of outreach efforts for CHIP and Medicaid with other social services or community programs.

- In December 2009, nine states received a total of almost $73 million in performance bonuses after adopting policies to simplify enrollment into CHIP and Medicaid and meeting enrollment growth thresholds.

- Since CHIPRA was enacted, more than half of states have made changes to either simplify enrollment or renewal in CHIP and Medicaid or expand eligibility. Nine states increased income eligibility limits for children in 2009.

- In December 2009, HHS released for public comment an initial set of recommended quality measures, covering duration of coverage, the availability of different types of care, and availability of care in different settings.

- In February 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) selected 10 states or multistate collaborations to receive $100 million over five years to test quality measures for children, a pediatric electronic health record system and other health information technology, new models of pediatric care delivery, and other strategies. These projects are just getting under way.

In this issue's Ask the Expert column, Jocelyn Guyer, co-executive director of the Georgetown Center for Children and Families, discusses opportunities and challenges that CHIPRA and the recently enacted national health reform offer states in improving the quality of health care for children. Snapshots describe Illinois' efforts to improve children's health care quality through the CHIPRA grant, New Mexico's use of such funding to expand their outreach efforts, and Louisiana's recent implementation of Express Lane Eligibility to streamline Medicaid and CHIP enrollment and renewal for children.

Background

Medicaid and CHIP together provide public health coverage to nearly one-third of children in the United States.1 Established in 1997 to encourage states to expand coverage to uninsured low- and moderate-income children by providing enhanced federal matching funds to state contributions, CHIP was reauthorized through FY 2013 through the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009.

CHIPRA strengthened support for states' outreach and enrollment efforts to identify eligible children, but its more far-reaching effect is likely to come from the program's substantial federal support of states' efforts to improve the quality of care in CHIP and Medicaid. The recently passed national health reform law further promotes quality improvement and delivery system reforms, reflecting a growing movement across the health care system to enhance quality and accountability.

CHIPRA provides a total of $225 million for quality improvement activities over 2009 to 2013. It establishes many different programs and incentives, some with short timeframes and others that will develop and continue over many years. The activities, which operate at the federal and state levels, are designed to advance quality of care and improve access by reducing barriers to enrollment and renewal (Table 1).

Table 1: Quality Provisions in CHIPRA Core Measures for Child Health Quality – Requires HHS to develop, test, and disseminate a set of core child health quality measures for CHIP and Medicaid programs, as well as the managed care entities they contract with, by January 1, 2010. The initial set of recommended measures was released for public comment in December 2009; it includes measures of duration of coverage, availability of different types of care, and availability of care in different settings. By 2011, HHS will develop a standardized reporting format for states and provide other technical assistance to enhance states' reporting capabilities and encourage the use of a comparable set of measures nationwide. Pediatric Quality Measures Program – Establishes an ongoing program to improve on and expand the initial set of core measures, including providing grants for developing and testing child health quality measures. New State Reporting Requirements – Requires annual public reporting on child health quality, with most states receiving enhanced administrative funding in Medicaid for reporting activities. States are encouraged, but not required, to use the new core measures. Quality Improvement and Health Information Technology Demonstration Grants – Provides a total of $100 million ($20 million annually) for a demonstration project in which up to 10 states or multistate groups receive grants to implement and evaluate child health quality measures and increase their use of health information technology to improve children's care. Managed Care Standards for CHIP – Applies Medicaid managed care consumer protections and standards for quality assurance to CHIP, effective for health plan contracts beginning July 1, 2009, and requires the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to report to Congress by August 2010 on the adequacy of Medicaid payment rates for managed care organizations. Model Electronic Health Record – Establishes a program to promote development of a model electronic health record system for children, to be used in CHIP and Medicaid. IOM and GAO Studies on Access and Quality – Requires the Institute of Medicine (IOM) to complete a report by July 2010 on the state of quality measurement for children's health care, and requires GAO by February 2011 to conduct a study evaluating and recommending ways to improve children's access to care in CHIP and Medicaid. Source: Center for Children and Families, Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. The Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009: Overview and Summary, March 2009. |

Quality Measurement and Improvement

CHIPRA's quality and access provisions apply not only to CHIP but also to children enrolled in Medicaid, broadening its impact to include virtually all publicly financed health care for children. This formalized overlap of CHIP policy into Medicaid reflects and builds on the varying degrees of integration of CHIP and Medicaid that already exist in the states. "The fact that CHIPRA extended enhanced quality reporting requirements to Medicaid is a big step forward," says Lisa Simpson, M.B., B.Ch., M.P.H., who directs the Child Policy Research Center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati. "Quality reporting is a 'big win' and an area where Medicaid can learn from CHIP."

CHIP has historically drawn from quality measurement and reporting strategies that were more prevalent in private insurance and managed care than in fee-for-service Medicaid.2 Each state's CHIP program is required to file a detailed annual report to CMS, setting out its goals, performance measures, and progress, including in improving the quality of care.3 "CHIP was enacted at a time when national attention to quality measurement and improvement was emerging and growing across the health care system," Simpson says. Along with a variety of other federal investments, it has contributed to states' understanding of quality issues.

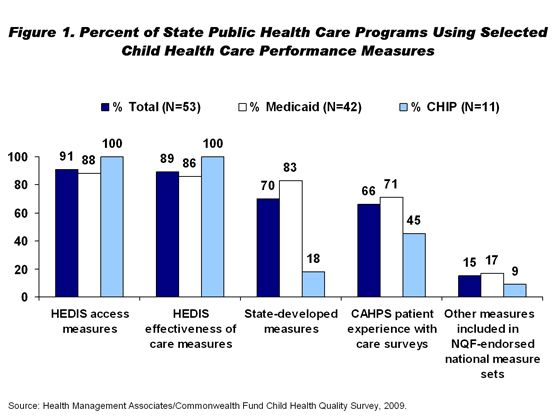

However, CHIP reporting on quality so far has not been fully standardized across the states, though research has identified wide variation in health system performance for children. Further standardizing measurement could help identify opportunities for improvement. CMS encourages states to use a group of measures from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set developed by the National Committee for Quality Assurance, but states may adapt some measures and add others that reflect their priorities.4 A survey by The Commonwealth Fund and Health Management Associates found that 18 percent of CHIP programs supplemented national measures on child health with state-specific measures, while 83 percent of Medicaid programs did so (Figure 1).5 In addition, different numbers of states report on different quality measures; one study found that the number or states reporting various measures ranged from 10 to 34.6

Medicaid and CHIP leaders in some states have expressed support for further standardization of measures and the use of common metrics to compare data nationally, in addition to increasing use of measures that focus on outcomes rather than processes and a number of other priorities.7 CHIPRA expands mandatory reporting requirements, applies Medicaid managed care quality and consumer protections to CHIP, and will establish a standardized format for state annual reports. It also encourages voluntary quality reporting using the set of core measures being developed as a result of the law, which presents an opportunity to standardize reporting on a national scale. It remains to be seen how rapidly states will adopt the new measures.

Simpson noted that the largest investments in CHIPRA are in quality measurement, which will help to identify opportunities for quality improvement. States that are not involved in the CHIPRA quality demonstration grant program (described below) may need additional assistance to identify these opportunities. Quality improvement activities in CHIP programs have historically been limited, due to a variety of financial and logistical barriers that have precluded performance-based financial bonuses and other efforts.8

Enrollment and Outreach

CHIP administrative simplification and outreach have had substantial "spillover" effects on Medicaid, boosting enrollment of children across both programs. This effect can occur even in states in which spending on Medicaid outreach or expansion is not a priority. After CHIP's implementation, in 1997, approximately half of the growth in publicly financed coverage for low-income children through 2004 was in Medicaid.9

States' Progress Implementing CHIPRA

Challenging economic conditions have increased demand for publicly financed health coverage, while at the same time making it more difficult for states to expand or maintain their public programs.10 However, CHIPRA has contributed to progress in several areas, from extending the CHIP program (with its enhanced federal match) through 2013, to significant grant funding for outreach and quality measurement. According to a recent HHS report, since CHIPRA was enacted, over half of states have made changes to either simplify enrollment or renewal in CHIP and Medicaid or expand eligibility. Nine states increased income eligibility limits for children in 2009.

Quality Improvement and Health Information Technology Grants

In February 2010, HHS awarded 10 demonstration grants to states or inter-state collaborations, totaling $100 million over five years. The grant funds will be used to:11

- experiment with and evaluate new measures for the quality of care for children in CHIP and Medicaid;

- promote the use of health information technology in care for these children;

- evaluate provider-based models to improve the delivery of children's health care services in CHIP and Medicaid; and

- demonstrate the impact of a model electronic health record format for children, which is ultimately intended to improve quality and reduce costs.

Grantees are taking a variety of approaches to meeting these goals, focusing on different populations, challenges, and delivery system strategies and often tackling multiple issues. For example:

- Colorado and New Mexico will receive about $7.8 million over five years. They will form an Interstate Alliance of School-Based Health Centers to integrate school-based health services, using a medical home approach. Their goals are to improve care for underserved school-aged children and adolescents; enhance screening, preventive services, and management of chronic conditions; and encourage adolescents to take an active role in their own health and care.

- Maryland, in partnership with Georgia and Wyoming, will use a grant totaling nearly $11 million over five years to implement a care management initiative to control costs and improve health and social outcomes for children in Medicaid and CHIP with serious behavioral health needs. It will include a variety of services, not yet fully defined, that supplement those typically covered by Medicaid and will incorporate the use of health IT to support clinical decisions.

- Oregon, Alaska, and West Virginia, three states with substantial low-income rural populations, will use a total of $11,277,361 over five years to develop and validate quality measures and test patient-centered care delivery models and improvements in health IT infrastructure.

This issue's Illinois Snapshot discusses that state's use of CHIPRA quality demonstration grant funding.

Outreach Grants

CHIPRA also provides $100 million in grants for states to conduct outreach to increase enrollment of eligible children in CHIP and Medicaid. In September 2009, HHS awarded $40 million to 69 grantees, including state agencies, safety net health care organizations, and community and faith-based organizations. In addition, $10 million of the $100 million is reserved for an outreach campaign at the national level, and another $10 million is dedicated to outreach and enrollment of Native American children through Indian Health Service providers. The two-year grants awarded so far have ranged in size from less than $70,000 to nearly $1 million.

As with the quality grantees, outreach grantees will implement and evaluate a range of strategies, including expanding their use of outreach workers, developing innovative outreach strategies, increasing their use of technology to streamline enrollment, and further integrating outreach for CHIP and Medicaid with other social services or community programs. Examples include:

- The Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which administers the state's Medicaid program and CHIP, is using its nearly $1 million grant to develop a comprehensive strategy for streamlining information about obtaining health benefits, and enrolling and retaining eligible children, including through data matching with tax information and school lunch programs. It also will develop an online application tool that can provide real-time decisions for Medicaid and CHIP applications.

- In California, the Providence Little Company of Mary Foundation, which is affiliated with a Catholic health system, received $317,144 to conduct outreach through community-based organizations and employers, targeting populations in six low-income Los Angeles–area communities with high rates of uninsurance and Spanish-speaking residents.

- In Florida, Fanm Ayisyen Nan Miyami, Inc., an advocacy and social services organization for Haitian women and families, will use $69,102 to partner with the Jackson Health System and the Department of Children and Families to conduct outreach to uninsured children in the Haitian community in the Miami–Dade County area.

The grants are a welcome, if limited, source of funding for outreach activities at a time when budget pressures might otherwise prevent states from taking on new projects. With the passage of health reform, states must maintain their Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels in order to receive any federal funding, and state programs are also beginning the extensive efforts that will be needed to implement health reform. With state budget crises as the backdrop for all these policy developments, it remains to be seen how CHIPRA-funded efforts will fare among many competing priorities in the coming years. This issue's New Mexico Snapshot explores the state's activities using CHIPRA outreach grant funding in greater detail.

Bonus Payments for Administrative Simplifications and Enrollment Growth

In addition to funding for additional outreach, CHIPRA provides bonus payments to encourage states to enroll children who are already eligible for Medicaid and CHIP. States that have in place five of eight strategies to streamline enrollment and renewal—and increase their enrollment above certain targets—receive a payment for each additional child in order to help compensate for the cost to the state of providing that coverage. The payments range from 15 to 62.5 percent of the average cost of covering the child, increasing as states enroll more children above the target number. In December 2009, nine states (AK, AL, IL, LA, MI, NJ, NM, OR, and WA) received a total of almost $73 million in these bonuses. This issue's Louisiana Snapshot discusses the state's recent implementation of Express Lane Eligibility, one of the simplification strategies CHIPRA promotes.

The Role of Health Reform

Over the coming decade, the national health reform provisions will lead to a significant expansion of public coverage. The new law preserves the CHIP program in its current form, extends funding for CHIP through 2015, and requires states to maintain eligibility levels for children in CHIP and Medicaid until 2019. It also provides a 23 percentage point increase in the federal matching rate for CHIP payments in 2015 and beyond.12 While a detailed discussion of all the implications of these changes for CHIP is beyond the scope of this States in Action, there are a few key areas in which reform may affect or interact with the quality improvement and enrollment efforts launched by CHIPRA.

It is possible that the continuation of CHIP as a distinct program may help sustain CHIPRA's emphasis on access, quality measurement, and improvement for children's care. Health reform also established a variety of pilot programs to promote delivery system reforms and innovation in public programs, including Medicaid, which could help identify and spread successful strategies to pediatric care. Future changes under health reform will affect CHIP and Medicaid enrollment; for example, once health insurance exchanges are established, individuals will be able to apply online not only for coverage in private health plans sold through the exchanges, but also for Medicaid and CHIP.

While national health reform opens great opportunities for new enrollment, children's health policy expert Jocelyn Guyer notes in this month's Ask the Expert that ongoing economic constraints and the demands of implementing other health care reform provisions may make it challenging for states to maintain their focus on children's coverage and quality.

1 In June 2008, CHIP covered nearly 5 million children, while Medicaid covered nearly 23 million. The number of children covered in Medicaid increased to nearly 25 million in June 2009.

2 The use of managed care plans has also been more prevalent in CHIP than in Medicaid, though Medicaid's reliance on managed care—and thus the prevalence of the monitoring systems these plans use—has also been growing.

3 L. Partridge, Review of Access and Quality of Care in SCHIP Using Standardized National Performance Measures (Washington, D.C.: National Health Policy Forum, April 2007).

4 HEDIS measures are an example of how quality measurement relates to enrollment issues. Because the measures are predicated on people being continuously enrolled for 12 months, quality measurement becomes more difficult and less accurate when people move into and out of public coverage for shorter periods; V. K. Smith, J. N. Edwards, E. Reagan et al., Medicaid and CHIP Strategies for Improving Child Health (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, July 2009).

5 V. K. Smith, J. N. Edwards, E. Reagan et al., 2009.

6 L. Partridge, 2007.

7 V. K. Smith, J. N. Edwards, E. Regan et al., 2009.

8 Ibid.; states with separate CHIP and Medicaid programs have the option to establish CHIP benefit packages that are similar to private coverage and more limited than the comprehensive Medicaid Early Prevention, Screening, Detection and Treatment package. While this issue would benefit from ongoing evaluation, CHIP benefits are likely to be adequate for most children. Children with disabilities or serious mental illness might need more extensive coverage, but they are more likely than children without such conditions to be enrolled in Medicaid.

9 L. Dubay, J. Guyer, C. Mann et al., "Medicaid at the Ten-Year Anniversary of SCHIP: Looking Back and Moving Forward," Health Affairs, 2007 26(2):370–81.

10 D. Cohen Ross, M. Jarlenski, S. Artiga et al., A Foundation for Health Reform: Findings of an Annual 50-State Survey of Eligibility Rules, Enrollment and Renewal Procedures, and Cost-Sharing Practices in Medicaid and CHIP for Children and Parents During 2009 (Washington, D.C.: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, December 2009); the Medicaid funding increase enacted as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, also known as the stimulus plan, has played an important role in preserving and enhancing coverage for children as the recession has increased demand for CHIP and Medicaid while simultaneously squeezing state resources. A potential funding extension from December 2010 to June 2011 is under consideration in Congress, though tough fiscal conditions in states will outlast any extension likely to be enacted.

11 State Demo Grants, Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) of 2009. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/CHIPRA/15_StateDemo.asp, accessed March 2010.

12 The legislation assumes that the program will be reauthorized before 2016.

For More Information See: L. Simpson, G. Fairbrother, J. Touchner et al., Implementation Choices for the Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, September 2009). Children's Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act: One Year Later—Connecting Kids to Coverage (Washington, D.C.: Department of Health and Human Services, February 2010). Resources on health reform and children's coverage from the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute's Center for Children and Families. |