By Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein

In an effort to lower the costs of treating frail, elderly patients with advanced illnesses and improve treatment outcomes, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation is testing whether providing these patients with timely, home-based primary care services will break the cycle of repeated emergency department visits and hospitalizations so often seen in this fragile population.

Enabled by the Affordable Care Act, the "Independence at Home (IAH) initiative targets Medicare patients with functional impairments and multiple chronic conditions such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Exhibit 1). This subset of patients is increasingly worrisome to policymakers because as a group they comprise about a quarter of beneficiaries but account for roughly two-thirds of the program's expenditures. And their numbers are expected to increase dramatically with the aging of the population.1

One of the challenges of caring for frail elderly patients is that they are often too sick or disabled to easily visit the doctor when they need care, making it hard for physicians to detect and respond to changes in health status—such as difficulty breathing or weight gain—that can snowball into medical emergencies. "They need a chronic care management system that is available to them 24/7 and they need active management to prevent unnecessary emergency department visits and hospitalizations," says Constance Row, executive director of the Edgewood, Md.–based American Academy of Home Care Medicine, a professional association that has worked to help providers and other organizations set up home care medicine programs, despite low reimbursement and other challenges.

Exhibit 1

To be enrolled in the IAH program, Medicare beneficiaries must:

- Have two or more chronic conditions,

- Have been hospitalized in the past 12 months,

- Have received rehabilitative services in the past 12 months (at a skilled nursing facility, home health, or inpatient/outpatient facility services),

- Require assistance for two or more activities of daily living, and

- Not be enrolled in Medicare Advantage Part C or the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE).

Models of Home-Based Primary Care

Many of the 18 health care organizations that have signed on to the three-year IAH demonstration are members of Row's association. Some are small nonprofits with as few as three primary care providers; the largest has 57. As a group they are providing home visits and care coordination services to 8,000 frail, elderly Medicare beneficiaries using teams led by physicians or nurse practitioners. If the organizations succeed at reducing health care spending for designated enrollees by more than 5 percent—and also achieve certain quality benchmarks—they will receive an 80 percent share of the additional savings. The quality metrics track processes known to reduce hospitalizations and readmissions, including follow-up within 48 hours of a hospital admission, discharge, and emergency department (ED) visit; providing in-home medication reconciliation within 48 hours of a discharge or ED visit; annual documentation of patient preferences; all-cause readmission rates within 30 days; admissions for ambulatory care–sensitive (ACS) conditions; and ED visit rates for ACS conditions. The shared savings payments may be essential to supporting such programs, most of which are supported by grants or subsidized by hospitals as part of their community benefit work.

While the demonstration is only halfway through, some participants are seeing positive results. Soon after joining the program and adding more intensive services for patients transitioning between sites of care, Portland, Oregon–based HouseCall Providers, a standalone nonprofit that serves 1,800 patients a year, saw hospital readmissions drop for this group to 3 percent in the first 15 months of the program from a practice average of 17 percent.

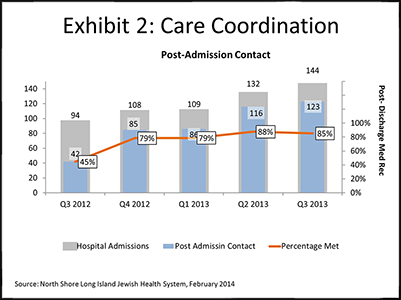

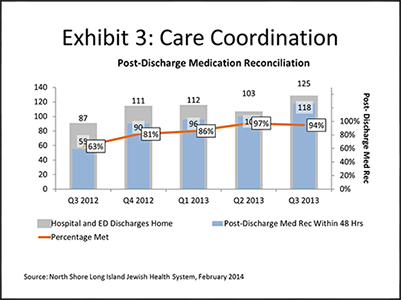

North Shore Long Island Jewish health system, which operates 16 hospitals in the Greater New York area, has also seen significant improvement in coordinating care for IAH and other House Calls patients—nearly doubling the proportion who receive postadmission contact within 48 hours from 2012 to 2013 and performing medication reconciliation 48 hours after discharge for nearly all patients (Exhibits 2 and 3). "We are proud of these results," says Kristofer Smith, M.D., medical director of Care Solutions, North Shore's care management organization. "Our patients are admitted to about 20 different hospitals in a given year—so reaching out to their providers is a difficult task."

North Shore also has been able to reduce admission rates among all House Calls patients—from 12.95 percent in the seven- to nine-month period before enrollment to 5.3 percent seven to nine months afterward—in part because of its Community Paramedicine effort, which dovetails with its House Calls program by providing an alternative to a hospital or ED visit on nights and weekends. The target, Smith says, are patients who fall into the "middle ground: they are not in extremis, but it can't wait until morning, either." When patients experience problems after hours, House Calls physicians can provide medical orders to paramedics and help decide whether they should treat them at home or in the hospital.

While these results are preliminary and their impact on cost is not yet known, results from more long-running initiatives—like the Department of Veterans Affairs' Home-Based Primary Care program, which began in 1972 and now serves 31,000 patients a day—suggest they can have a dramatic impact. The VA program has reduced the need for acute care and thus overall costs to the VA and Medicare by 24 percent by relying on robust teams, led by a medical director and including nurses, social workers, and mental health providers as well as rehabilitation therapists, dieticians, and others as needed. They "create a unified care plan as a team," says Thomas Edes, M.D., director of geriatrics and extended care for the VA's clinical operations. "They make decisions based on clinical judgment; maybe one week a respiratory therapist needs to go out, and another week a nurse will do the home visit."

|

North Shore Long Island Jewish Health System's Physician House Calls Program |

In Northern California, Sutter Health's Advanced Illness Management (AIM) program, begun in the late 1990s on the foundation of its existing home health services, is another well-known model. The notion, according to Khue Nguyen, a creator of the AIM program and cofounder of ACIStrategies, a consulting organization, was to "leverage what's already available. Most advanced illness patients were already utilizing home health services, so we reengineered those to deliver care management." Nurses and social workers do the bulk of the home visits, supported by physicians and telemedicine tools. By 2010 the program was having an impact among 800 patients in the Sacramento/Sierra region, resulting in an over 60 percent reduction in hospital days, and an 80 percent to 90 percent reduction in ICU days. In 2012, Sutter received a $13 million grant from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to spread the model throughout Northern California.

Engaging Patients on Their TurfProponents of the model say that home visits offer a window into patients' lives, often enabling providers to uncover issues beyond vital signs and lab results—such as social isolation, unsafe housing conditions, or poor nutrition—that, if unaddressed, may lead to medical problems. While some home-care programs use remote monitoring devices to help monitor patients, the approach is more "high-touch" than "high-tech," relying on frequent, in-person contact with patients and their caregivers.

Moving the site of care to patients' homes also shifts the power dynamics, says William Zafirau, M.D., a geriatrician who makes home visits through the Center for Connected Care at the Cleveland Clinic, another IAH participant. "You are on their turf, a guest in their house. That leads to a whole level of honesty you never get in the office," he says. During a recent home visit, Zafirau discovered that a patient wasn't taking any of his prescribed medications, a fact that may not have come up if he hadn't been in his home and asked to see his pill bottles. "People don't like to tell their M.D.s they are not doing what we tell them to do. But [with this patient] we were we able to have a discussion of sides effects, costs—things that are barriers to people being adherent. We were able to reduce his medications by about half, and he agreed he would give it a try," he says.

Home visits can facilitate this kind of shared decision-making—providing time and a level of comfort among patients, providers, and their caregivers for discussions about patients' goals as well as advanced care planning, proponents say. "A one-shot conversation in the hospital before discharge to try to get you to sign a DNR [a "Do Not Resuscitate" order] is no substitute for conversations in the home, over time," says Brad Stuart, M.D., another of AIM's creators at Sutter and now CEO of ACI Strategies. "What you get then are advanced directives from people who really understand their illness, have found some emotional resolution, and understand that the end may be coming." With most Americans saying they'd prefer to be at home than in hospitals or nursing homes at the end of their lives, this alone could curtail overuse of interventions for those with advanced illness.2

Barriers to Spread

To date, there has been little incentive for health systems to pursue this model under fee-for-service reimbursement because the staff and resources required to provide home-based care make it more expensive than traditional office visits. Value-based contracts and global payments may create some incentive to invest in the model, as the efficiencies that result from reduced numbers of ED and hospital visits will accrue to health care providers.

For North Shore, which participates in an accountable care organization and recently launched its own health plan, the IAH demonstration offers the opportunity to build on its efforts to more proactively manage populations, specifically the frail elderly. "We thought the demo could be a lever for change—it will give us insight into whether we are doing a good job for these patients—and whether we can reduce costs," Smith says.

But the business case is a work in progress. Oregon's HouseCall Providers has been negotiating with local payers to provide additional per-member per-month reimbursement to cover their service. Meanwhile, the Brooklyn–based House Calls for the Homebound has been able to be self-supporting by maximizing use of providers' time and pursuing other efficiencies (see sidebar). The Coalition to Transform Advanced Care, a broad-based membership organization with insurers, health systems, advocacy groups, and professional associations, is reviewing different home-based primary care models to identify factors key to success and the economic model needed to sustain them.3

Another challenge is the lack of geriatric or other primary care providers available or willing to work with frail elders—a problem that may be addressed to some extent if the business case improves. Those who practice in the area say it brings a great deal of satisfaction. "It can be very rewarding taking care of people who fall through the cracks," says Robert Kaplan, M.D., with America's Disabled Inc., an IAH participant that has been providing physician visits to homebound, disabled patients since 1989.

Spreading the model may mean leveraging the skills of nurse practitioners and other mid-level clinical providers, says Smith. With 10,000 people newly qualifying for Medicare each day, "it is hopeless to think we can build programs like this to meet the clinical need on the backs of physicians," he says.

Other efforts—including the linkAges Connect initiative led by Sutter Health's Palo Alto Medical Foundation and a faith-based initiative being piloted by the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care—are looking beyond health systems to identify community resources that might be deployed to support frail elders in their homes. The goal is to ameliorate the isolation and depression many frail elders experience (factors that can themselves contribute to poor health) and create a network of neighborhood caregivers, should help be needed.4

"This issue is part of our lives," says Joanne Lynn, M.D., director of the Center for Elder Care and Advanced Illness at the Altarum Institute (see Q&A). "It's not other people; it's us, older."

Notes

1"Advanced Illness Care: Key Statistics," Coalition to Transform Advanced Care, Dec. 10, 2012, available at https://docs.google.com/file/d/0B2Yr38cBOUqzUkhWLWJyZ25YQlU/edit.

2 Ibid.

3 This work is supported in part by a grant from The Commonwealth Fund.

4The linkAges Connect initiative aims to increase frail elders' face-to-face interactions with their neighbors and other community members and is also deploying technology to monitor passive signals in frail elders' homes (such as utility and water usage patterns) to detect indicators that something might be wrong and alert caregivers.