Sickle cell disease is a life-threatening blood disorder that affects around 100,000 Americans, mostly African Americans. In addition to coping with the disease itself, many face a host of other challenges, like getting to the hospital for treatment, paying bills, and figuring out where their next meal will come from.

On the latest episode of The Dose, Dr. Cecelia Calhoun talks about her work helping children and young adults with sickle cell cope with these issues day to day. Calhoun is one of the first experts to receive the Pozen Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Leadership at Yale University to advance her work on health disparities.

Listen, and then subscribe to The Dose so you never miss an episode.

Transcript

CECELIA CALHOUN: When I think about the patients that I see now, one is a young lady who is finishing up her sophomore year at UMSL, which is a university here in Missouri. And she’s incredibly hard working. She’s premed and wants to be a doctor. She also works full time. And she has sickle cell disease. And what that means for her as a student is that in addition to her coursework and to working her job, that she comes to the clinic every six to eight weeks to get automated red cell exchange.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: What does that do to her life? And also, how does that make her feel physically, emotionally? It must be draining.

CECELIA CALHOUN: Exactly. This particular treatment involves a lot of prep work, so she has to come and get labs one day to make sure that we have everything is properly arranged and calculated for the red cell exchange, and then she comes for the treatment, which is — patients kind of get hooked up to, it looks like a dialysis machine, where basically you filter out their entire blood volume. So that takes a while, too. And then we kind of replace some of the volume that we took away.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Hi everyone, welcome to The Dose. On the next three episodes, we’re going to be talking about disparities in health care. You just heard from Cecelia Calhoun. Cecelia is a pediatric and young adult hematologist at Washington University in St. Louis. She treats patients who have sickle cell disease, which is a life-threatening blood disorder. Sickle cell disease affects around 100,000 Americans, mostly African Americans. Cecelia’s work, helping children and young adults with sickle cell disease, shows how complex the connections are between health and socioeconomic factors. In 2018, she became one of the first experts to receive the Pozen Commonwealth Fund Fellowship in Minority Health Leadership at Yale University. Cecelia, welcome to the show.

Let’s take a minute to cover some of the basics. Very simply, what is sickle cell disease?

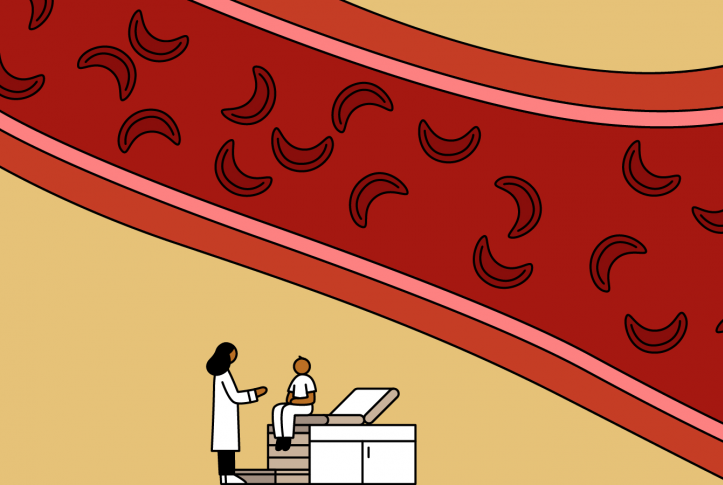

CECELIA CALHOUN: Sickle cell disease is an inherited disorder where your red blood cells are misshapen and deformed. Or they’re shaped like a banana or a sickle. And in addition to being shaped differently, they’re also quite sticky and quite rigid. And so what this means is that if our red blood cells are pipes, we can imagine normal red blood cells flowing through the pipes, passing each other, swimming freely around in our plasma, making it to their final destination and delivering oxygen to our tissues.

But with sickle cell disease, as those rigid, hard cells pass through those pipes, they’re scratching up the side of those pipes, they’re sticking to the sides of them, and they’re sticking to one another and they cause blockages. And so, if blood isn’t able to get to where it needs to, that tissue doesn’t get oxygen and it kind of dies a little bit. All the clinical manifestations that we see, and so most commonly that’s pain, but also in our body. So our lungs, our eyes. Specifically, our brain. And when I say our brain, I mean, really, really bad strokes.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: How does this young woman remind you of yourself as someone who is also young and also wanted to be a doctor?

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yes, so much like her, I didn’t necessarily come from the rosiest background. I grew up on the East Side of Detroit and there are socioeconomic disparity. But I had really dedicated parents and I had a support team. So I hope to be part of this young woman’s support team. You know, I want to be one of the people that helps her achieve her dreams, because for me, that was absolutely essential.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Where does your patient live? Where do you care for her?

CECELIA CALHOUN: She lives in North County, which is a St. Louis suburb where — which is predominantly African American. Our hospital is downtown — I would say sort of downtown.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Is it difficult for her to get there for her treatment?

CECELIA CALHOUN: So she actually takes public transportation, she takes the bus. And the reason that that’s difficult is because of the time commitment, the irregularities of the bus schedule. And the fact that it just takes so long.

And that’s just something that’s not unique to my patients. You know, I think when I think about the two biggest logistical challenges that adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease that I see face, number one is insurance coverage and number two is transportation. So she takes public transportation to get here. I’m not exactly sure how many buses, but I know that it’s over two. I know that it involves a transfer and, you know, just a day like today when it’s 90 degrees and she’s still trying to get homework done and make it to work, you know, it can definitely be a challenge, as I’m sure you can imagine.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I can only imagine. And then after treatment, again, she probably feels physically depleted and then she has to go back on a bus, transfer to another bus — that just sounds exhausting. And so making the time and also the emotional energy to go through something like this is really, really incredible. And, as you say, it’s really important that she’s diligent about coming in to get this treatment so that she can manage her disease.

CECELIA CALHOUN: I’m so, so incredibly proud of her, because she’s able to master this. And it’s a challenge that I don’t think many people could and certainly not that many of my young adults can do.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Well, let’s talk about one of those patients then.

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yeah, I would say most of the patients I see — they want to do the best for themselves. They want to live and thrive. But they really are just struggling to survive, because of the circumstances in which they grew up. So there’s one patient in particular I think about who — he was cared for at our hospital as a child. But subsequently got caught up in the criminal justice system. And came to me when he was 19 to reestablish care. He faces several social challenges in that he has almost no family support. He often is homeless. He has limited access to his medications.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: What happened? How did he lose his family support? How did he get caught up in the criminal justice system?

CECELIA CALHOUN: He comes from a single-parent home. And his mother had to work to support his family. And so he was left alone a lot. And at a very young age in an attempt to fit in — and we’ve talked about this very candidly, you know — he got arrested for car theft and then burglary. He was about 16 I think when that happened. And many of his youth years had been kind of sucked up. So it’s been a little bit of a cycle, you know? If you’re young and immature and you make a mistake, once you enter the criminal justice system there’s a certain stigma around that and he hasn’t really been able to escape that.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: How does somebody like that have the time and the ability to manage a disease that requires several hours every six weeks?

CECELIA CALHOUN: So the short answer is I don’t think they do. And that’s one of the big problems when we think about how to support our young people with sickle cell disease. This is a population that’s truly affected by social determinants of health. So the things outside of the hospital, things external to the health care system that challenge the way that they’re able to manage themselves. So if you are just trying to figure out how to pay your bills or how you’re going to get from Point A to Point B, or what — where your next meal’s going to come from, it’s going to be a challenge for you until you have bad pain to think about, hey, maybe I should go see my hematologist, or hey, I know that I have this treatment scheduled but I don’t really have a way to get there and I have five dollars as my whole entire food budget for the rest of the week. I think it’s one of the areas that we really, really need to work on, commit to and find solutions to if we really wanna help children and young adults and adolescents with sickle cell disease, not just survive but thrive.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And obviously this is something that you want to do. But tell me a little bit about the beginning and how you got interested in studying sickle cell disease and also in treating patients with it.

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yes, so when I was in med school I actually thought that I wanted to be a surgeon. [laughs] And during your latter years of school, you do clinical rotations. And my favorite rotation was on a pediatric floor, which also happened to be the hematology and oncology floor. But also that was the first time that I actually got to care in some way for a patient with sickle cell disease. And it was the first time that I saw the deleterious consequences of sickle cell disease, when I saw an eight-year-old girl who had had an overt stroke. And she couldn’t move her entire left side. Through caring for patients with sickle cell, I realized the huge gap in transition as we help them move to the next phase of their life and receive adult care.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Uh-huh. And why isn’t that a seamless process to begin with?

CECELIA CALHOUN: So in a general sense the transition from pediatric to adult care is a major issue for many disease processes. But when we think about special populations like children with type 1 diabetes or children with congenital heart disease or the children that I care for, sickle cell disease, it becomes even more complicated. It’s when the more insidious disease processes are becoming more apparent. You’re going through puberty and your body is changing and the effects on your disease are greater. There may be a change in your home environment. Certainly a change in resources like your insurance coverage. And then changes in your academic environment. And then we also have to make sure that that process of going from the pediatric setting to the adult setting is clear, that there is good communication between providers and that there are adult providers that are available to care for these patients. So it’s pretty complex. And in patients with sickle cell disease who, like I said before, are really affected by social determinants of health and stigma — that process becomes a lot more complicated.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: So as I’m thinking through this idea of transitions, now children can stay on their parents’ health insurance until they’re 26 years old. But what happens to someone whose parents are uninsured? How are they getting care for sickle cell disease?

CECELIA CALHOUN: So in the pediatric population and certainly here at our hospital, the majority of the children that we treat rely on government insurance. And so, as these patients get older, either they don’t meet criteria for continued government insurance or they don’t know how to access it once it’s fallen off. And that’s a huge, huge barrier for the patients that I treat.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: It’s almost like — it’s like a cliff. You go one day from being able to get care and then suddenly you’re not able to have that anymore.

CECELIA CALHOUN: That’s exactly it. And it’s when they fall off, if they don’t have a transition, that that’s when the morbidity and mortality really start to rise and that’s what the data shows us.

What I really want to do is figure out how we as a health care system make a bridge from pediatric care to adult care. And so my current work focuses on the design and structure of transition programs so that hospitals can bridge that gap between pediatric and adult care.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And do you have any stories about patients whom you have seen and have had a successful or smooth transition from pediatric to adult care?

CECELIA CALHOUN: So the first question I always ask a patient when I see him is, when you tell your friends you have sickle cell disease, how do you explain it to them? Because that tells me, one, if they’re talking to people about sickle cell, because some of them aren’t. And it also helps me understand how I can support them. When I think of kind of the extreme of this situation — I had one patient who came to me a little over a year ago. When I first saw him in the clinic, we went through his 17 medications and I asked him which ones he was taking, and he was like, my pain medications.

And we talked about how this is the only medication that’s proven to help his life last longer. We talked about how he can manage his own pain at home, we talked about how to call us and use us as a resource. I started seeing him weekly to optimize his care, and now he hasn’t been hospitalized in months.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Uh-huh.

CECELIA CALHOUN: And he wants his own apartment and he wants to drive and he wants to date and now he’s really able to move toward those things because he’s not living moment to moment wondering if he’s going to be in the hospital.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And that’s amazing that you were able to get him up to this point. Maybe what we should also talk about is treatment and cure. So you said that there’s only one cure and that’s bone marrow transplant.

CECELIA CALHOUN: Uh-huh.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: But most patients don’t have access to this?

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yes, so bone marrow transplant effectively is when you take stem cells from one person and you put them into another person and allow them to replicate.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Uh-huh.

CECELIA CALHOUN: That is a gross oversimplification. So for sickle cell disease and transplant, it’s incredibly complicated because, number one, it’s very challenging to find a match. Because African Americans are such a heterogeneous population and a mix of different genes and DNA, it’s hard to find someone that will be an exact match. And also because there are really not enough people of color on the bone marrow transplant registry. That places a huge challenge. And then, also it’s a very expensive procedure.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: The other treatment that that I read a little bit about is gene therapy, but it seems like this isn’t really being widely used. Can you talk about why?

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yes. So actually the promise of gene therapy is extremely exciting. One of the main challenges of bone marrow transplant is it’s really challenging for people to find a match. Gene therapy removes the need for you to find a match because with gene therapy you’re a match to yourself. Basically what happens is your own stem cells are harvested and outside of your body your DNA is, through a special process called Crispr, is modified so that you don’t have sickle cell disease, and then you give it back to the person and let those new cells kind of grow within their home space. It’s a very, very exciting therapy but it’s very new, and so it will take time and experience before it becomes widely available to patients.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Uh-huh. And I imagine it’s also pretty expensive, right?

CECELIA CALHOUN: Yeah, just like bone marrow transplant and even more so, this is using cutting-edge technology to do these kinds of genetic manipulations, and so it is quite expensive, and whether or not insurance companies are going to cover it, because certainly like we talked about, this is not a population that can afford very expensive medical procedures.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: This is pessimistic, but I can’t help but think, given that sickle cell disease predominantly affects African Americans, that it’s not really a national priority to, one, do more research into how to treat it, but then two, make sure that the treatment is widely accessible to more people.

CECELIA CALHOUN: I think you’re absolutely right. I think that really what sickle cell disease represents is opportunity. Opportunity for us to do better as a scientific community, opportunity for us to do better as health care providers and as a health care system, but also as a society. And I think that as we look at the challenges that patients with sickle cell disease face, if we are able to kick it in gear and make moves in this population, I think it is an example of what we can do overall.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Well, I think that’s the right note to end on then. So thank you so much for agreeing to be on the show.

CECELIA CALHOUN: Thank you.