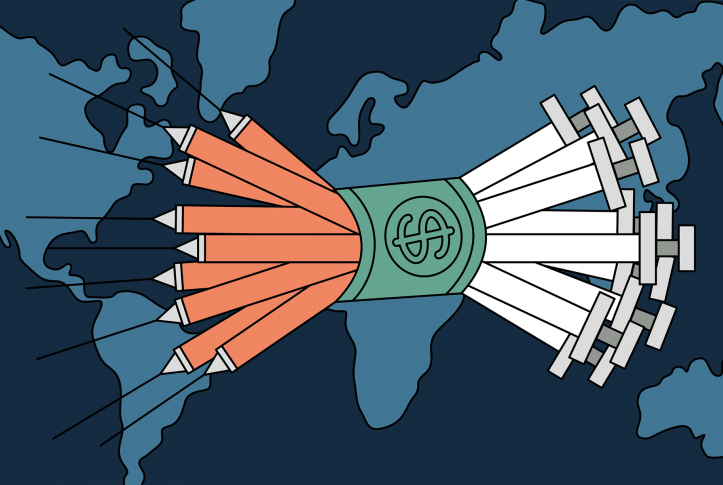

While rich countries are doling out booster shots of the COVID-19 vaccine, many poor countries have vaccinated less than 5 percent of their population. And, while many leaders agree that vaccinating the world is the only way out of the pandemic, vaccines are still not moving around the globe in a rapid and equitable manner.

This is because “we live in a hierarchy of health,” says Priti Krishtel, a health justice lawyer and cofounder of I-MAK, a nonprofit focused on building a more just and equitable medicines system.

On the latest episode of The Dose podcast, Krishtel argues that unequal access to vaccines is rooted in a long-standing system of incentives that governs drug development and distribution. She says rethinking the drug patent regime and other incentives — and working together to ensure every country gets a fair allocation of vaccines — is the way to end this and future pandemics.

Transcript

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Hi everyone, welcome to The Dose. The COVID-19 pandemic has driven home gaping global inequities. Rich countries like the U.S. have more than enough vaccines for anyone who wants a shot. But the world’s poorest countries have vaccinated only a tiny fraction of their people. One of the major forces that drives the distribution of medicines like vaccines is patents. So today we’re going to talk about how the patent regime could be transformed to make sure that people everywhere have access to the medical treatments they need, regardless of where they live.

My guest, Priti Krishtel, is a health justice lawyer and cofounder of I-MAK, a nonprofit devoted to building a more just and equitable medicine system. Her work is focused on exposing the structural inequities that affect access to medicines across the global south and in the U.S. Right now that includes everything from advocating for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines to ensuring that the Biden–Harris administration is prioritizing equity in the Patent and Trademark Office. We’ll talk about all of that and more.

Priti, welcome to the show.

PRITI KRISHTEL: Hi, thanks for having me.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Before we dive in, if you could make one quick fix to ensure greater equity and access to medicines, what would it be?

PRITI KRISHTEL: Right now, my quick fix would be to ensure that when we give taxpayer dollars to fund research and development, that there would be strings attached to it. Since the beginning of the pandemic, governments worldwide, led by our own, have invested upwards of $110 billion in vaccine development. And yet, for all of that investment, we have no ownership stake in the vaccines themselves, and don’t have the ability to dictate who can produce the vaccine and who can distribute it. And I think it’s a big mistake.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: At a COVID-19 summit at the U.N. General Assembly in September, President Biden said, “Vaccinating the world is the ultimate solution to COVID-19.” This recognition that we need global access to medicines — it’s something you’ve been working on for years. How is the pandemic reshaping your work?

PRITI KRISHTEL: For those of us who work on access to medicines and vaccines, we’ve been at the forefront of every epidemic and pandemic for the last 25 years. I think how COVID is reshaping our work is, between the pandemic and between the racial awakening we’re seeing in the U.S. and around the world, I think people are starting to understand systems, and the ways that systems have been designed and the ways that they work in practice with wholly new eyes, or lenses. And it’s giving us the opportunity to show the way it works in practice in real time. So people can start to connect the dots for themselves. And because each person has a stake, and whether or not they get the vaccine and their own family stay safe, and their understanding interconnectedness in a way that maybe we didn’t before as a society. I think it’s giving us a new opportunity to drive change forward.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: You’ve suggested concrete ways of reimagining the patent process and intellectual property regime. Now, do you see the pandemic accelerating efforts to correct these dysfunctions?

PRITI KRISHTEL: I think there’s more appetite right now for change than there’s ever been. I think that people understand that leaving medicine, vaccine ventilator, PPE distribution, to the market is not going to help lead us out of this pandemic as quickly as possible. And I think people understand that we need a new set of rules to ensure that either bringing this pandemic to a close, or thinking about being better prepared for future ones, we need a better system and governments have to play a greater leadership role in that new system.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And walk me through, you know, rapid fire, what would that new system even look like?

PRITI KRISHTEL: Sure. So there’s a few different ways I think about this. The first is just looking at a basic set of rules. For example, I was mentioning to you earlier, when public funding is deployed. Let’s take Moderna, for example, which was nearly 100 percent funded for its vaccine development by taxpayers to the tune of $2.6 billion and built on years of publicly funded research. We, as the United States government, on behalf of taxpayers, did not retain ownership rights in that funding and in the inevitable invention. And Moderna now stands poised to commercialize that platform for many other diseases. So this is a an example of the kind of situation our current system is bringing to bear. And it’s the kind of thing that with a new set of rules, Moderna could partner with the U.S. government, be given significant funding, could make some reasonable profit. But there would be a fair set of rules in place so that the U.S. government could then take control and ownership of the vaccine and start to partner with manufacturers all over the world to scale up supply and access.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: There’s a huge gap between the proportion of fully vaccinated people in rich and poor countries. Is there an evolving global strategy to distribute vaccines more equitably?

PRITI KRISHTEL: You know, the situation today is really stark. Most of the world is not getting the vaccines that they need to come out of this pandemic. There is no strategy to bring us out of it. We know, based on the research, that if we employed a collaborative approach, if we had a different kind of system where the whole world worked together to ensure that every country got an equitable allocation of the COVID-19 vaccine, we would be able to cut the number of deaths in half. In other words, we would be able to save twice as many lives. But that is not the system we have today. We are still relying on the market, we are still relying on the benevolence of private actors, and we are still relying on a donation- and charity-based system that is failing us at every step.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: So, trying to think of reasons that we’re in this place, does this has something to do with the manufacturing capacity in the global south?

PRITI KRISHTEL: Oftentimes, we’re hearing this argument here in the United States — and it’s being very strongly advanced by the industry — that capacity does not exist in other countries to make any of the vaccines. And that argument, frankly, is just not true. You know, UNICEF alone supplies 2.4 billion vaccines to children all over the world every year; over half of those come from India. there are many countries in the world already producing mRNA vaccines. And there are many, many companies who have now told the World Health Organization that they stand ready to build their capacity to make these vaccines. Companies for example, that make biologics already, or make other types of vaccines. But unfortunately, we’ve concentrated the power to make these decisions on private companies who are not incentivized to actually share their knowledge.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And how are inequities around race and gender exacerbated by the global imbalance in vaccine access?

PRITI KRISHTEL: So I think from a global perspective, they’re saying that this pandemic is going to set back progress for women and girls worldwide by decades. So the longer we wait to correct what is clearly a failing system — for access to medicines and vaccines — the more we are setting back women and girls everywhere. Women have been forced to leave the workforce, girls are dropping out of school. And all signs indicate that they’re actually not going to return. Women make up most of the frontline workers. In many countries, for example, for the health care workforce, domestic violence and sexual violence is on the rise worldwide. And it’s particularly acute for refugees and for displaced people generally. And so it’s a really, you know, acute gender equity issue when we talk about access to medicines, because the impact of not being able to get medical products is different for women and girls than it is for everybody else.

From a racial equity lens, you know, there are a couple of different ways to think about this. One is just simply that when you look at the map, globally, of who’s getting vaccines and who’s not, it is predominantly majority-white countries who are vaccinated right now. So that is kind of a more straightforward way to think about it. And then even within those countries, when you look at who is less likely to be vaccinated — and the barriers that have been documented in the U.K., in the U.S., in other countries. Depending on the country, the term is different, but I’ll say people of color here are facing more barriers, are less likely to be vaccinated in different places. And so, these are all very serious racial equity concerns.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: You’re talking about this really deep-rooted global inequity that’s existed for so long, and against this background, high-income countries are giving people booster shots. The CDC in September recommended booster shots of the COVID-19 vaccine for people over 65, people with underlying medical conditions, and for health care workers and others at risk because of their occupation. What do you think about this?

PRITI KRISHTEL: I think we live in a hierarchy of health, you know, some people are used to getting things first, some people are used to not getting things at all. And when the pandemic started, what our movement was saying from day one is that that hierarchy is going to play out with access to treatments, vaccines, oxygen, you name it, and it has unfortunately. I think the argument about boosters or the debate, the global debate about boosters, falls right into this framework. The director general of the WHO is saying that it is unconscionable that we’re talking about scaling boosters across the population in high-income countries like ours, when most health care workers are deeply vulnerable and at-risk communities across the global south are not getting their first dose. And so it’s a tough one. I think that there is a growing chorus of health care professionals who are lending their voice to this debate, saying that until the facts are in, that boosters are actually required, it is really just unconscionable that we’re talking about distributing boosters to the mainstream population in the U.S.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I mean, you’re painting a very scary picture. And I do want to try to talk at least a little bit about solutions. So let’s talk about the World Trade Organization. Now, the WTO has some power potentially because it regulates intellectual property [IP] rights across countries. And many experts have called for waivers on IP protections around vaccines, so that we can speed up global manufacturing, as we were talking about earlier. How successful has the U.S. been in leading this movement towards temporary waivers?

PRITI KRISHTEL: So I’d first note that it’s South Africa and India who are leading the waiver process. They first put forth a proposal last October, where they asked for a temporary waiver on IP. They were joined by over 100 countries now, who echoed that demand, saying that it would be impossible to meet needs on the ground from a clinical perspective unless IP was waived across medical products, and unless they could scale up a response. Now the U.S. in May, which is a full eight months after the request was made, we did signal support verbally for the waiver. But unfortunately, our actions have not backed up that historic verbal support that we provided.

All reports are indicating that the U.S. is showing up at the World Trade Organization meetings without pushing and persuading our allies in the G7 to follow suit. You know the European Union countries, the U.K., are not following suit and are resisting the request for a waiver. We are not putting a concrete proposal down on paper and leading by example, and it’s really unfortunate. Every month that goes by, so many lives are being lost.

And so I think what many people are calling for across the global south right now is for real leadership. And people are looking to the U.S. to demonstrate it, since we did verbally signal that we were going to lead on this request for a waiver of IP. And along with that, it’s important to note that waiving IP alone will not get us the fix that we need. We also need to be sharing knowledge and making investments to ensure that as many manufacturers as possible around the world can actually get going in a really practical way.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: You know, the other thing that people are talking about is COVAX. How relevant is that program in improving global access to vaccines?

PRITI KRISHTEL: You know, I think COVAX is failing. I think it has been failing for a long time. And I think it will continue to be to fail, to be quite honest with you, because it is predicated on a market-based mechanism that relies on charity. And charity alone is never going to get us out of this pandemic. And I say this not to be critical of COVAX, but at the end of the day, when we cede power through our rules and laws to private actors and ask them to work in a market-based structure, where their incentives, not because they are bad people, but because those are the incentives that are in place for their institutions, is to drive revenue. It’s not to make as many people as possible survive the pandemic. There is a disconnect there. When are we going to explicitly recognize that the system we have in place does not work for global pandemics and a special set of rules is necessary?

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And what would this special set of rules look like? What would a better framework look like?

PRITI KRISHTEL: So I keep coming back to the public funding, because I think it is a route in these moments of crisis. It’s a lever that can be pulled. I think a new set of rules would say that we need public funding to be predicated on partial ownership rights or shared ownership rights, and that the U.S. government in those cases would be able to take ownership of the product and do whatever was necessary to get manufacturing going around the world. I think also, even in the cases of private actors like Pfizer, there does come a point where governments do have to step in and take over. You know, a lot is made of the wartime analogy. I’m usually not the biggest fan of those, but I think there is precedent to show that in times of extreme crisis, governments have to do what is necessary, even if it rattles the marketplace for a while.

I keep pointing back to this example from early in the pandemic, where Gilead Sciences, a California-based company, had started to see promise at the time in remdesivir as a treatment for COVID-19. Remdesivir, actually, has not panned out as the treatment that we all hoped it would be. But at the time, you know, there was a lot of optimism around the drug. And when Gilead Sciences announced that they wanted to partner with several low- and middle-income country manufacturers, basically what we’re asking for on vaccines today, right, we want to see scale-up — partnership and licensing is a very logical way to get that done — the market responded very unfavorably. Their stock tanked that day. And by the end of the week, it was in the pits.

And so what I really took from that moment, watching that happen is, here’s a company trying to actually do the right thing. But our system of incentives is set up to ask them to do exactly the opposite. And the only way that’s going to change is if we set up a new set of rules that incentivizes the sharing of knowledge. And as we move into this new era, with climate change on the rise and pandemics on the rise and greater catastrophes than we’ve known in our history on the planet, so far, there has to be a different way forward, and the evolution of this system to meet the current moment.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And so to incentivize the transfer of knowledge instead of locking it up, as you say, who will make this new set of rules? What will it look like on the ground to have this be enacted?

PRITI KRISHTEL: Policymakers are going to have to do this hard work. Policymakers here and in countries around the world. That’s why paying attention to the World Trade Organization’s IP waiver under the TRIPS agreement is a really good place to start. Because we are going to hear from countries, you know, low- and middle-income countries, what their needs actually are. And I don’t know that we do enough listening as Americans.

You know, for example, with this IP waiver, the whole conversation in the U.S. has gotten distorted, where we keep talking about vaccines. But if you really listen to what South Africa, India, and the 100 other countries are talking about, they’re talking about different examples of medical products. So, for example, when there was a black fungus outbreak during the surge in India, that was a really good example of where they needed a product called liposomal amphotericin. And those monopolies were standing in the way of getting more suppliers going. They needed help, they didn’t get it in time, black fungus started to spread to neighboring countries like Nepal and other places.

So these are the kinds of things I think next time, on the ground, if during these IP waiver negotiations, we can actually try not to set the bar too low. If we actually look ahead and have the foresight to say, what should this new set of rules look like internationally? And what are we willing to bring into domestic legislation to better prepare us for next time? To keep our families and community safe? To keep the global community safe? I think this is the place to start. And this work has to happen over the course of the next 12 months.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Let’s look ahead now to the next 12 months and then what happens after that. Is the pandemic showing us what the next iteration of the global intellectual property regime could look like?

PRITI KRISHTEL: I think it is. I think the IP waiver conversations — the fact that we are even at the table as the United States, it’s historic. It is not a moment to undervalue how significant this step was, in the first time we’ve seen in 25 years, the U.S. government really recognized that the architecture of this system is not the right one to serve us going forward. That is a huge step. And then the next 12 months, how that gets translated into practice, into the details on that set of rules, is going to be critical.

There’s another piece to this though, when we’re talking about saving lives, urgently, while we’re changing the rules of the game, to ensure equity now and for generations to come. There is a piece of this around democratization that I think has not been talked about enough. So to fundamentally reshape our global health system into one that works for everyone, I do think that we need to look at, along that system, the medicine system, from drug development through to access — if you get under the hood, and start looking closely as my organization has done for the last 20 years, you’ll see that people are excluded, actually, from many of these systems.

And the patent system lies at the heart of that because it’s the power center. There is no public participation in the patent system. Whether, you know, you want to say that’s by design or whether it’s just an oversight or afterthought, you know, all of those perspectives could be debated. But the facts are clear. There are no mechanisms for people to participate in the patent system writ large, or here in the United States, at the Patent and Trademark Office itself as the agency that is tasked with being the gatekeeper for the social contract that says, “If you invent something, you get a monopoly, but then the public gets the benefit.” When that social contract isn’t working out, it should, in an ideal world, be the PTO that is the gatekeeper for that. And it’s not really happening. And in my view, it’s not happening because we don’t have the public’s voices in that system, providing that much-needed balance to industry.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: And so how do we get the public voices to provide that balance? What would it look like for people to participate as you described?

PRITI KRISHTEL: I think there’s a few different ways. The USPTO has something called the Public Advisory Committee. And there’s very little . . . actually, there’s no true public representation. And what I mean by that is this: the agency historically has viewed its customer as people who are applying for patents — major drug companies, big tech, universities. But everyday Americans who are affected by those monopoly rights that are given and that we’re not getting access to, there’s no seat at the table for us on that committee, or in other places. Many of the roundtables and the requests for comment, they’re very technical, this is a very technocratic system. And so if we’re serious now about increasing public participation, we have to design for voices to be heard. And that doesn’t mean, for example, the person living with diabetes has to go out and become a patent law expert. What it means is that we value and center and prioritize the person who’s not able to get their insulin, that human experience is brought in, those voices are heard. And then there is a meeting of the minds between those perspectives and those tasked with evaluating whether patents should be granted at all.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Before I let you go, I wanted to ask one last question. We’ve been talking about how COVID-19 has exacerbated all these inequities and access to medicines. And for both of us, you know, we have family in India, and this has become such a personal issue. Could you talk a little bit about what it has been like to be doing the work you’re doing and, at the same time, witness what your loved ones are experiencing so many miles away?

PRITI KRISHTEL: Honestly, it’s been really surreal. I’m sure you’ve heard this, but during the surge in India, for example, there wasn’t a household in India that was left untouched. Delta variant came in strong, it moved fast, it took a lot of people out, including my family members. And it was really heart-wrenching to see, you know, so many of them hadn’t gotten the vaccine yet or had gotten their first dose. So it’s the sort of helplessness you feel, just like we felt at the beginning of the HIV epidemic, where you know the thing is there, you know, the silver bullet, the medicine or the vaccine, you know it exists, and it’s just not reaching the people who need them. And I think what was really illuminating is, it didn’t matter whether it was my cousin who works in a factory or, you know, my more well-off uncle — it didn’t matter where they sat on the economic ladder. They didn’t get it because their country wasn’t at the front of the line in our hierarchy of health.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Thanks so much for being here today, Priti.

PRITI KRISHTEL: My pleasure. Thank you.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: This episode of The Dose was produced by Jody Becker, Andrea Muraskin, Naomi Leibowitz, and Joshua Tallman. Special thanks to Barry Scholl for editing, Jen Wilson and Rose Wong for our art and design, and Paul Frame for web support. Our theme music is “Arizona Moon” by Blue Dot Sessions. Additional music by Podington Bear. Our website is thedose.show. There you’ll find show notes and other resources. That’s it for The Dose. I’m Shanoor Seervai. Thanks for listening.

Show Notes

Bio: Priti Krishtel