To help consumers enroll in the recently opened health insurance marketplaces, the Affordable Care Act created outreach and consumer assistance positions such as "navigators," in-person assisters, and certified application counselors. Though they are subject to uniform federal standards, in practice, these programs range widely from state to state, because of the adoption of laws and regulations in many states that make it difficult for navigators to perform their jobs, as well as differences in funding for consumer assistance for different types of marketplaces. In this post, the first of a two part-series, we will examine the new restrictions; our next post will look at the how the limited funding for outreach and education for federally facilitated marketplaces, compared with state-run or state partnership marketplaces, may be limiting consumer outreach efforts in those states.

This summer, we reported that many states with federally facilitated marketplaces had imposed requirements more stringent than the federal rules governing the navigator program. Supporters of these efforts say that more regulations are necessary to ensure that navigators are well trained and protective of consumers' rights. However, some of the new restrictions seem likely to prevent navigators and other consumer assisters from doing the jobs they were created to do.

Scrutiny of Assistance Programs

In July, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released final regulations for navigators and assisters. In August, it awarded grants to more than 100 organizations selected as navigators in the federally facilitated and partnership marketplaces. HHS also published extensive mandatory training materials to drill assisters on the health law and their responsibilities to consumers (including, importantly, their obligation to protect the privacy and security of personal information).

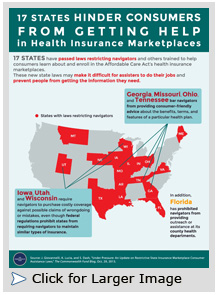

At the same time, scrutiny and criticism of assistance programs has increased. At the federal level, the House Energy and Commerce Committee launched inquiries into many of the organizations that received federal navigator grants. In the states, policymakers continued to limit these programs through a variety of means. Seventeen states with federally facilitated or partnership marketplaces have now passed navigator legislation: Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Of these, more than half have begun the formal rulemaking process. Meanwhile, other states acted in less formal ways, as Florida did when it prohibited navigators from providing outreach or assistance at any of its county health departments.

At the same time, scrutiny and criticism of assistance programs has increased. At the federal level, the House Energy and Commerce Committee launched inquiries into many of the organizations that received federal navigator grants. In the states, policymakers continued to limit these programs through a variety of means. Seventeen states with federally facilitated or partnership marketplaces have now passed navigator legislation: Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Maine, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Of these, more than half have begun the formal rulemaking process. Meanwhile, other states acted in less formal ways, as Florida did when it prohibited navigators from providing outreach or assistance at any of its county health departments.

Regulating Consumer Assisters

As with many other aspects of the Affordable Care Act, states enjoy considerable leeway to customize requirements for consumer assisters, so long as they do not interfere with federal law. Some states, particularly those operating their own marketplaces, used this freedom to empower assisters. Maryland, for instance, directs navigators to help with plan selection based on the unique needs of each applicant. This state requirement, which is consistent with federal regulations, expressly recognizes that consumer assistance services may involve giving advice about the specific terms and benefits of a marketplace plan.

In contrast, many states that chose not to develop a state-based marketplace have been slow to support consumer outreach (though opportunities to do so remain). These states have shown no hesitation, however, in acting to regulate consumer assistance programs. The 17 states identified above adopted restrictions on navigators and other assisters that test the limits of the health law’s flexibility. For example:

- Restrictions on consumer-friendly advice. Twelve states restrict the advice navigators can offer consumers. Four—Georgia, Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee—go so far as to bar them from giving advice about the benefits, terms, and features of a particular health plan, despite the fact that federal rules require navigators to clarify distinctions among plans and assist people in making informed decisions about what coverage to choose.

- Burdensome financial requirements. Three states—Iowa, Utah, and Wisconsin—insist that navigators secure a surety bond or other insurance against claims of wrongdoing or mistake, even though federal regulations prohibit states from requiring navigators to maintain errors and omissions coverage. A fourth state, Illinois, has authorized its insurance department to impose a similar requirement.

- Rules that reach beyond navigators. At least nine states cast a wide net when regulating consumer assistance. In Georgia and Illinois, for example, restrictions on providing advice about health plan particulars apply not just to navigators, but also to other individuals and community groups that help with outreach or enrollment. The broad scope of Tennessee’s regulations has led to multiple lawsuits and an agreement by the state to enforce its rules more narrowly (though they still apply to non-navigator assisters).

Whether these state requirements violate federal law is an open question, and the litigation in Tennessee may lead navigator organizations in other states to address the restrictions in the courts. In the meantime, uncertainty about what navigators are allowed to say or do in many states is causing some organizations to withdraw from the program. For Americans living in states with federally run marketplaces—where consumer outreach efforts have been modest to begin with—this chilling effect only makes it harder to learn about the health law and enroll in coverage.