As the United States struggles anew to contain COVID-19, concerns are growing regarding its long-term impact on mental health. Local reports cite increases in domestic violence calls and opioid overdose. Crisis hotline use is also rising, with some reports of staggering spikes. For example, calls to Los Angeles suicide and mental health hotlines have increased 8,000 percent. Modeling has suggested that the pandemic will lead to as many as 75,000 deaths from alcohol and drug misuse and suicide, increasing the total of COVID-related deaths. While national data are sparse, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Household Pulse Survey suggests that the proportion of U.S. adults with symptoms of anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder have quadrupled since before the pandemic, with the burden disproportionately borne by women and people of color.

Driving Factors

A number of factors may be driving these increases. The impact of the pandemic on social determinants of health, such as employment, income levels, and housing and food security, have threatened basic survival. Access to care in the U.S. also has been negatively affected — nearly one-quarter of adults surveyed in early November reported they had not received needed care in the past four weeks. Finally, throughout the pandemic, many individuals find themselves living with a perpetual sense of uncertainty, which is associated with outcomes ranging from negative psychological well-being to elevated blood pressure. Living with uncertainty also magnifies the psychological impact of other stressors.

Children are particularly vulnerable to the mental health effects of the pandemic resulting from school closures and the suspension of social activities, and also are affected by the stress their parents are experiencing. School closures have particularly impacted access to mental health care for children: more than half who use mental health services receive at least some services in school settings, with 35 percent receiving services exclusively in schools.

COVID Rates and Access to Mental Health

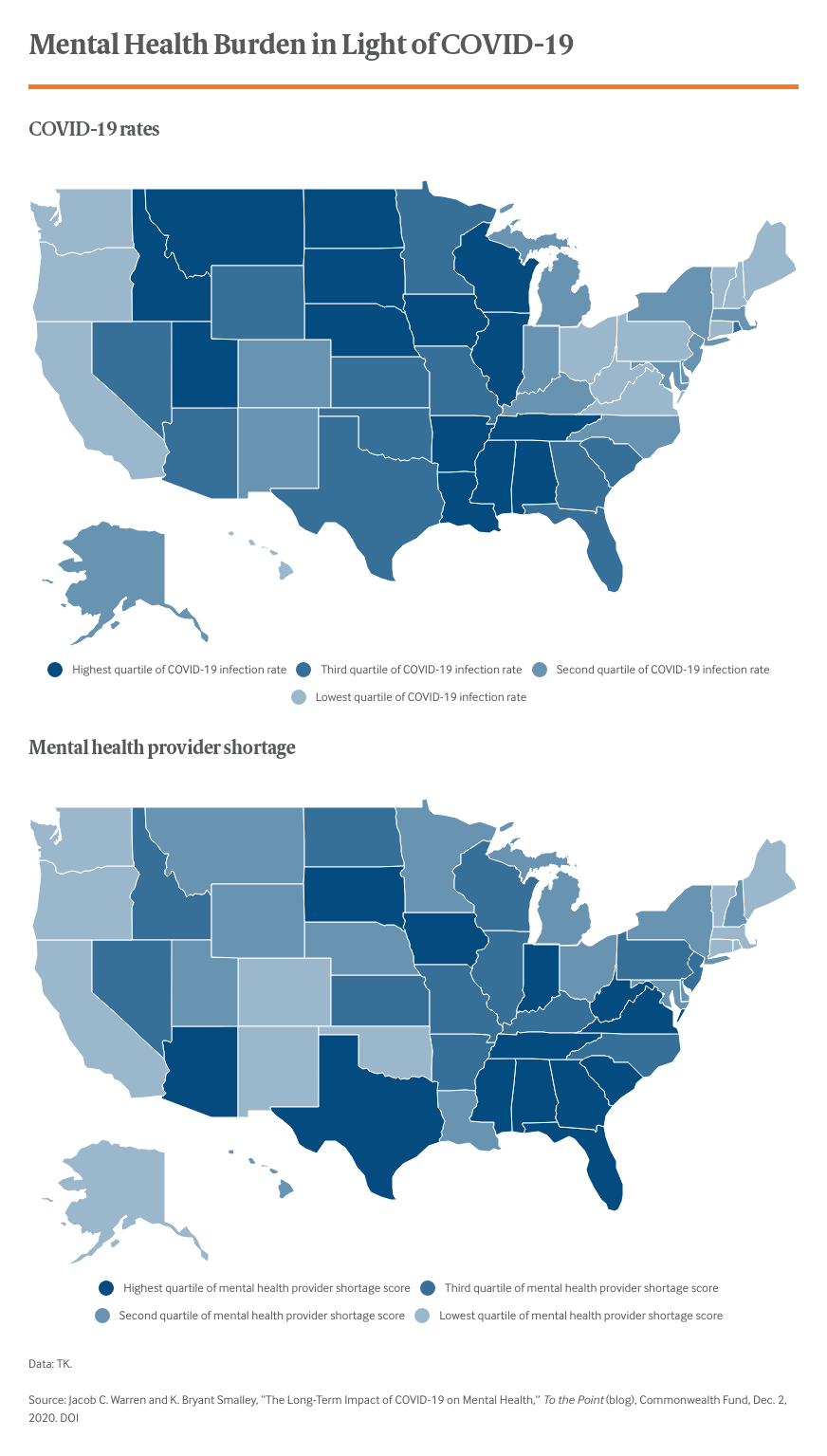

Addressing the mental health crisis through a single national strategy is complicated by the wide variation among states in overall rates of infection, access to care and availability of mental health providers. For instance, as of November 15, the states with the lowest infection rates per capita are Medicaid expansion states, where there is better access to care and providers. Alternatively, all nonexpansion states but one (North Carolina) are in the top half of per capita COVID infection rates. Of the 15 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid, four are in the highest quartile of both per capita COVID rates and mental health provider shortage severity. In responding to this crisis, states should consider the interplay of three factors — overall COVID burden, the availability of mental health providers to meet the anticipated surge in need, and the ability of residents to financially access mental health services even if they are available.

Strategies and Solutions

It is likely that the mental health fallout from the pandemic will continue to grow. The exacerbation of social determinants of health will last for years (and likely decades), which will have long-term implications for mental health. The 1918 flu pandemic led to reduced educational attainment, higher rates of physical disability, and lower income for individuals who were in utero during the pandemic, suggesting there may even be intergenerational effects.

States are already taking a variety of actions that could help mitigate the impact on residents’ mental health. While the need is great, so too is the opportunity for states to be proactive in planning for the growth in mental health needs. Moving forward, it will be important for states to consider:

- increasing the pipeline of mental health providers

- examining state insurance laws to ensure that mental health parity or equal treatment of mental health and substance use disorders is enforced

- bolstering telehealth infrastructures

- enacting plans to help children access the mental health resources previously received in schools.

When choosing approaches to implement, it is important to consider prevailing factors in the state. For instance, an initiative to increase the number of mental health providers that does not simultaneously look at the locations of shortages in such providers may end up misallocating resources. Finally, to plan effectively and respond strategically, it is critical that states implement stronger surveillance of mental health outcomes, which allows for rapid response to newly emerging needs.