By Brian Schilling

For a certain subset of patients, the thing that often gets in the way of receiving high-quality health care is simply being sick. This subset of very sick patients gets a lot of attention in medical circles for the simple reason that the care they receive is extremely expensive. They are among the 5 percent of patients who account for about 50 percent of health care spending, much of it on ineffective or inefficient care. It’s an article of faith among many in the health care world that if we could just improve care for this group, we could save an enormous amount of money.

But how, exactly? Efforts to improve the lot of the high-need patient are still being tested and evaluated. A handful of new programs focused on these patients are emphasizing relationship-building and focusing more intently on meeting patients’ nonmedical needs outside the doctor’s office. In this second part of our three-part series on high-need patients, we meet a patient and her care coordinator from the Medical Home Network in Chicago.

Laren, 62, Chicago

Through Blurred Vision, a Glimpse of Hope

In some ways, Laren may be the luckiest member of her very large family. With seven sisters and two brothers, she was the last member of the troop to be diagnosed with diabetes, in 2006. This shared family curse has left one brother on dialysis and a double amputee; several have vision problems and trouble walking; all are struggling. And while she may have been lucky to be last, Laren’s diagnosis didn’t feel lucky at all.

“It depressed me,” Laren said softly. “I really felt like, ‘Oh, well, that’s that.’”

Since that initial diagnosis, the disease has progressed, leading to problems with her legs and feet, increasing levels of neuropathy, low energy, and so on. She also has high blood pressure and struggles with depression.

For almost 10 years, with no health insurance and little social support, Laren managed her illnesses in a highly unproductive manner: she ignored them. There were occasional trips to the doctor or the ER, and on-again off-again attempts at insulin, but no routine of care and no real attempt to address underlying causes.

Then came the cataracts. “My vision got so bad I couldn’t see,” said Laren. “I couldn’t read my mail. How could I take medicine? I couldn’t even read the bottle. I couldn’t see faces.”

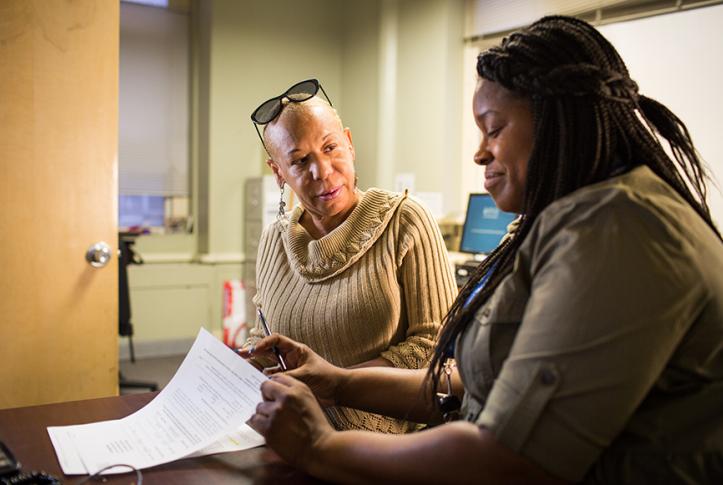

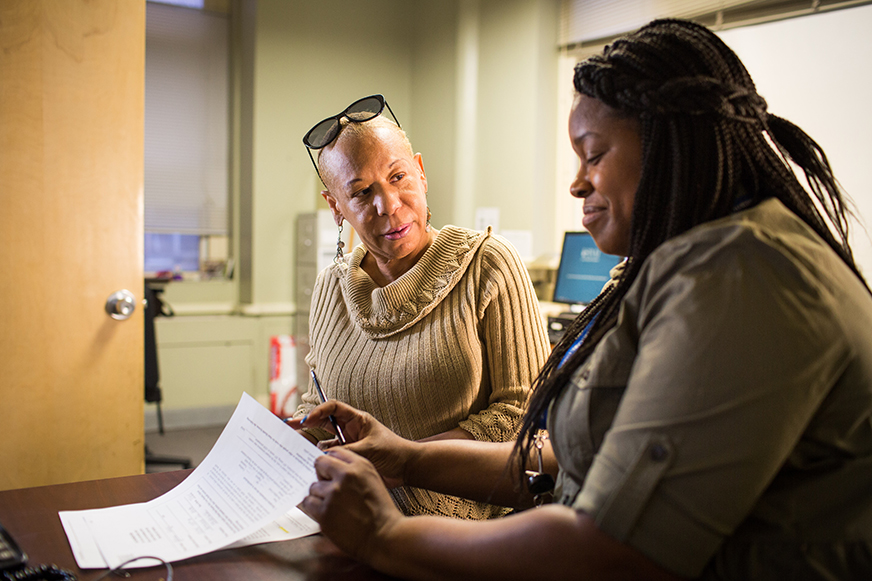

Laren’s despair deepened until she began to entertain thoughts of just ending things. At that point, about two years ago, she found herself in the psychiatric unit of Mt. Sinai Hospital on the south side of Chicago. Sinai treats a stream of patients facing similar challenges and is part of Chicago’s Medical Home Network (MHN), a broad alliance of clinics, hospitals, and other organizations that collaborate to improve care for the area’s underserved populations (see sidebar at bottom for details). Laren was assigned a case worker, Kim Reams-Parham-Parham, to help her get the care and support she needed.

Reams-Parham has been a case worker for two years, although she’s been employed by Sinai as a registered nurse for nearly 10 years. Reams-Parham, and other professionals like her throughout Chicago, participate in MHN both because it gives them an opportunity to build rewarding relationships with patients and because the organizations they work for have committed to working together wherever possible to control costs. In Reams-Parham’s role as a case worker, she’s responsible for about 70 patients. Some of these she sees almost daily, others far less frequently.

“I’m there when they need me,” said Reams-Parham. “But the goal is for them to not need me so I actually feel good when I can help people enough so that they don’t need to call—it means they’re on the right path.”

Laren says that some of the most invaluable support Reams-Parham provided wasn’t of a medical sort at all. Reams-Parham sat with Lauren and helped her fill out her Medicaid paperwork, something she’d been trying but unable to do for almost five years. As a result, she now has health coverage for the first time in recent memory. Reams-Parham also arranged transportation for Laren to and from various appointments, without which, Laren says, she simply wouldn’t have gone. And finally, she helped Lauren adjust to and follow her new insulin regimen, which involved self-administered injections four times a day.

But most importantly, Reams-Parham helped Laren get her sight back, scheduling cataract surgery in June on her right eye, and then in September on her left. Both surgeries were successful and Laren is taking advantage of her newfound freedom to move about on her own, regularly attending services and other functions at the New Covenant Baptist Church near her home.

“It’s nice to be able to go to church again,” she says. “You don’t really know what it means just to be able to see someone’s face.”

Laren describes her diabetes today as being “under control,” and she’s looking forward to a bright future.

Reams-Parham says she speaks to Laren only about once a month. “When I started working with the MHN effort, I was focused on meeting a set of performance targets. That’s still important, but now the satisfaction I get out of helping people is really what makes a difference to me.”

Next week’s issue will include the final part in our series on high-need patients, and will share the story of Somali immigrant and his care coordinate in Minneapolis.

Medical Home Network—Chicago

The Medical Home Network (MHN) was established in 2011 in Chicago with the backing of area hospitals, clinics, the Illinois Medicaid program, and dozens of other entities, to increase communication and data-sharing within the metropolitan area’s highly fractured delivery system. The effort has led to marked improvements in the quality of care available to many of Chicago’s most underserved and vulnerable residents. Today, 22 hospitals and more than 200 medical home sites can share patient data and information through MHN’s online platform, leading to efficiencies that have helped slash readmission rates (15%), increase timely follow-up care (more than 100%), boost engagement among the target population, and nearly triple the rate of area patients who have a health risk assessment on file (79%). The backbone of the MHN program is a battery of care coordinators who take a hands-on approach to ensuring that patient care is coordinated and that no one falls through the cracks. These care coordinators, who are employed at participating clinics, receive extensive training on changing patient health habits, linking patients to available community resources, leveraging technology to improve health, and ensuring that all participating entities have access to up-to-date information about patients in the system.

Staff: 34

Notable: Launched its own accountable care network in 2013