Community health workers who help patients navigate the health care system and work to address their social and economic needs have rarely been fully integrated into care teams. This issue reports on health care organizations that have integrated community health workers into multidisciplinary teams, which appears to be a factor in their success.

Community health workers—the frontline lay workers who serve as a bridge between clinicians and their patients—have been around for several decades in the U.S., but they have rarely been fully integrated into care teams for a variety of practical and cultural reasons. This is in spite of a growing body of evidence that community health workers (CHWs) in the U.S. and overseas can help the sickest and neediest patients improve their health and avoid costly emergency department and hospital visits (see graphic).1

Many CHWs come from the communities they serve, and often speak the same language—literally or figuratively—as the patients living there. They call upon that shared experience to build relationships with patients, and in turn use their knowledge of patients’ neighborhoods and cultures to help providers fine-tune their approaches to the patients they serve. In this way, they differ from social workers, nurse case managers, or others tasked with helping people with complex needs.

The people CHWs help are often those who providers find are their most challenging and yet may have the most to gain from effective communication and encouragement. In some cases, the information they gather from frank conversations with patients has been life-saving, as happened for a 16-year-old on a kidney transplant list in New Mexico. Covered by Molina Healthcare, which operates Medicaid and Medicare managed care plans throughout the country, the teen was assigned a community health worker because her nephrologist and care manager were concerned her family was struggling with the pre-transplant care.

The concern escalated after her nephrologist discovered the girl wasn’t taking her medications. After trying for months to find out why, he gave up and recommended she be removed from the transplant list. Both the mother and daughter insisted to the CHW that the teen was taking the medications. Eventually, however, the teen admitted to her CHW that she had been lying to her mother—and had not been taking her medications because her cousins had been taunting her with texts about her “rotten kidney” and telling her it would be better for everyone if she let herself die. “She was passively letting herself die,” says Dodie Grovet, the program’s training manager.

The CHW was able to find the girl a counselor, get her a new cell phone number, and she eventually began taking her medications.

“Patients do not always tell their doctors the truth, or the whole story, and doctors are forced to make strategic decisions based on incomplete information,” says Sergio Matos, executive director of the Community Health Worker Network of New York City. “CHWs can get to the core issues and find information that clinicians don’t have access to.”

Impact of Community Health Workers

A 2010 review found that many evaluations of CHW programs were weak, leading health system stakeholders to dismiss the evidence as anecdotal or, conversely, to set unrealistic expectations on what CHWs can do. But a recent New England Journal of Medicine Perspective noted that in the past five years many more rigorous studies of CHW programs have been published, leading to greater understanding of what works and pointing to specific ingredients for success.

The following round-up of evidence draws on selected studies on the impact of CHW programs.

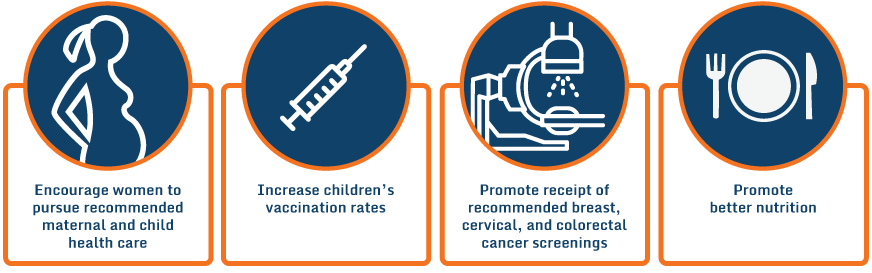

Community health worker programs have led to more appropriate use of preventive and primary care. For example, CHWs have been shown to:

Community health worker programs have also been shown to help improve disease outcomes for patients with asthma, hypertension, diabetes, cancer, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and depression, among other conditions.

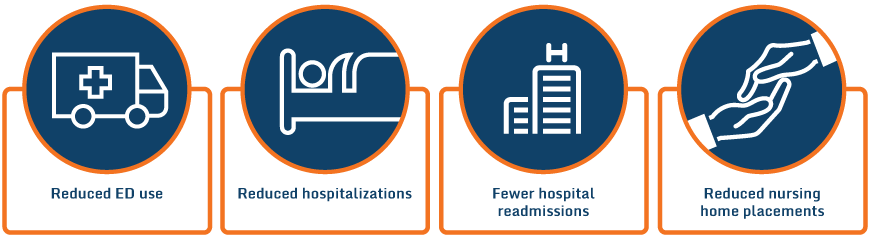

Documented savings in CHW programs have been attributed to:

Sources: J. N. Brownstein, G. R. Hirsch, E. L. Rosenthal et al., “Community Health Workers ‘101’ for Primary Care Providers and Other Stakeholders in Health Care Systems,” Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 2011 34(3):210–20, http://www.chwcentral.org/sites/default/files/Brownstein_CHWs%20101%20for%20primary%20care%20providers.pdf; “Community Health Workers: Getting the Job Done,” Network for Excellence in Health Innovation, http://www.nehi.net/writable/publication_files/file/jhf-nehi_chw_issue_brief_web_ready_.pdf; “Community Health Workers: A Review of the Program Evolution, Evidence on Effectiveness and Value, and Status of Workforce Development in New England,” Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, Draft Report, May 24, 2013, http://cepac.icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/CHW-Draft-Report-05-24-13-MASTER1.pdf; and Community Health Worker Toolkit, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/chw-toolkit.htm.

Difficulty of Classifying CHWs

It’s difficult to determine how many CHWs are currently working in the U.S. They are a mobile workforce, employed by local departments of health or public health agencies as well as health insurers and provider organizations and moving between clinics and hospitals and community settings such as schools, public housing developments, job sites, or people’s homes. Most work in poor communities, both in cities and rural areas. One estimate put the figure at more than 120,000, but this included expected growth in the workforce that didn’t come to pass because of the recession.1

They also go by many names—patient navigators, outreach workers, peer health educators, community health representatives (in American Indian/Alaska Native tribal communities), and promotoras de salud (in Hispanic communities). In recent years advocates have sought to clarify their role by promoting standard definitions and certification/credentialing programs, though there is some disagreement whether this will constrain CHWs’ freedom.3

This issue of Transforming Care reports on health care organizations that have integrated community health workers into multidisciplinary care teams, which appears to be a factor in their success. We also look at barriers organizations face in doing this—among them concerns about funding, training, and cultural differences between CHWs and clinicians.

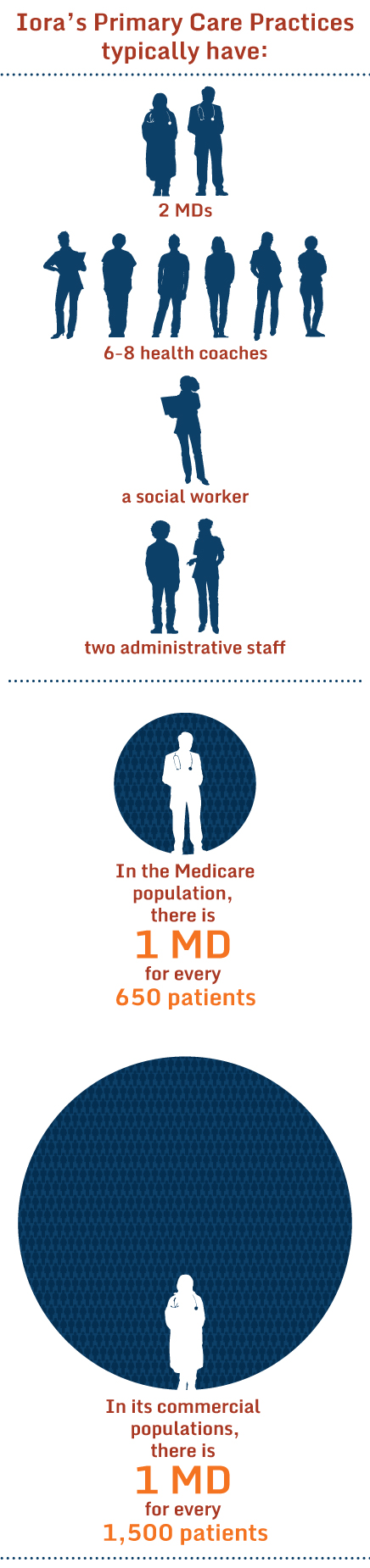

| See the Q & A with Iora Health’s Rushika Fernandopulle, M.D., on how his clinics incorporate health coaches. To hear from a community health worker, see our profile of a CHW working with those newly released from prison in San Francisco. |

Connecting to Sources of Support

One of CHWs’ key roles is to connect people to social services, legal services, housing support, or public insurance programs for which they may be eligible—doing everything from helping people fill out applications to reaching out to homeless people in shelters to making connections with service providers.

At Christus Spohn Health System, a Corpus Christi, Texas–based system, CHWs help uninsured patients navigate the health care system. They meet with patients, assess their needs, and work to build bridges between patients, primary care providers, and nonprofits that can help them.

One Christus CHW visited a woman in her early 30s who had been discharged from the hospital after experiencing complications from her asthma, diabetes, and hypertension. “We noticed she had not filled her medication or gone to see her doctor and were trying to figure out why,” says Liza Esparza, Christus’ director of transitional care. The CHW learned the woman’s water had been turned off and she was struggling to care for a disabled child—issues that meant her own health wasn’t a priority. The CHW was able to find local organizations to help her with water and electricity bills and later helped her find stable housing.

Encouraging Behavior Changes

CHWs are often trained to use motivational interviewing and other coaching techniques to encourage people to make changes to improve their health. At the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, they follow a strength-based approach to motivate patients with multiple chronic conditions who are not actively participating in their care. “Sometimes we ask what a good day looks like. They will say I don’t have good days,” says Diane Holland, clinical nurse researcher at Mayo. “It takes a lot of sophisticated problem-solving to recognize that they have strengths and build on them.” One CHW helped an elderly, socially isolated man with poorly controlled chronic conditions sign up for VA services so he could receive home health care and other support. He then found a way to help him get back to woodcarving—a cherished hobby he had given up because of his limited mobility—by creating a small, accessible workspace.

Catherine Vanderboom, clinical nurse researcher, says this approach is part of a strategy to broaden the definition of well being and identify nonmedical impediments to health. “We have found repeatedly—it’s pretty remarkable—when we bring a patient into the program, we hear about problems like finances, housing, and social isolation. It is really stepping back from that medical management to look at basic needs,” she says.

Offering Empathy and Building Trust

Another role of community health workers is to help people surmount linguistic or cultural barriers that prevent them from speaking honestly with their providers—some because of a deep-seated distrust of the medical establishment, for others because they are embarrassed to admit their failings or don’t want to disappoint their providers. With a still predominantly white and Asian medical workforce treating an increasingly diverse population, CHWs can serve as a trusted peer for patients.

Latecia Turner, a CHW working for Grand Rapids, Michigan–based Spectrum Health, draws on her own experience in caring for her diabetic mother when she talks to patients about their chronic conditions. “I let them know that I have struggles, too,” she says. “I let them know that they are not alone. I let them talk about their fears. And I offer them encouragement by saying where you see yourself now is not where you will always be.”

Partnering with Care Teams

CHWs are most effective, their advocates say, when they are fully integrated with multidisciplinary care teams—when they have access to patients’ health records, take part in case review meetings and rounds, and have a say in developing care plans.

Spectrum Health accomplishes this by using CHWs to complement the skills of nurses, as part of the Core Health program, run by a charitable arm of the health system that aims to improve population health. Recently, a Spectrum CHW and nurse took care of a 50-year-old morbidly obese man with asthma, diabetes, and hypertension who was hospitalized with an A1c level over 11. “While the nurse worked with his primary care doctor to review his prescriptions, the community health worker was able to call local pharmacies to find ones that could deliver and had the lowest copays,” says Bethany Swartz, supervisor of the program. The CHW also helped enroll the man in health insurance and taught him how to ride the bus so he could make it to his doctor’s office. After three months, his A1c level had dropped to 6.3 and he had lost 15 pounds.

Albert Slezinger, M.D., and Maria Murphy, a community health worker with Bronx-Lebanon, visiting a former patient at home.

The Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center in New York has used CHWs since 2007, beginning with a grant-funded pilot in one of its South Bronx medical homes that produced a return of $2 per $1 invested (based on reductions in admissions/emergency department visits and increased revenue from outpatient visits for patients who were considered high utilizers). The results led administrators to dedicate operational funds.4

Today, the system uses some 35 CHWs to help hospital patients prepare for discharge, track down those who don’t show up for appointments or need certain screenings, and make home visits to identify patients’ challenges and help them take steps to improve their health. In addition to training CHWs for this work, Bronx-Lebanon trains clinical staff in how to partner most effectively with CHWs. CHWs present their cases at team meetings, and medical residents go with them on home visits. “Residents say now I understand why my patient is unable to control his A1c: he’s living in a one-bedroom apartment with six other people,” says Jose Tiburcio, M.D., associate chair of the Department of Family Medicine and an attending physician.

Fostering relationships between residents and CHWs had its challenges at the outset, says Matos of the Community Health Worker Network of New York City, who worked with Bronx-Lebanon to evaluate the program. “When the CHWs first arrived the residents were uncomfortable with high school graduates being on the team. It led to a lot of tension, but by the end of the first year residents loved them and would go crazy if the CHWs didn’t come in,” he says.

Gathering Health Information and Facilitating Education

While many CHWs focus on the socioeconomic determinants of health, some organizations are pushing the boundaries of what they have traditionally done to support patient care. A new team of CHWs hired by the Los Angeles County Department of Health, for instance, connects patients to services, but the CHWs—25 now with 25 more to be hired next year—also accompany patients on visits, provide health coaching, follow protocols to support them after hospital discharge, and gather information about what medications they are and are not taking as recommended.

They also deliver 50-item biopsychosocial assessments, using the results to work with providers and patients to prioritize goals and create care plans, and draw on some 70 scripts to facilitate conversations about things like managing medications and chronic diseases, navigating the health care system, healthy eating on a budget, and spirituality and health. “We want to take CHWs’ unique knowledge and shared experience and weave it into the way we deliver care,” says Clemens Hong, M.D., medical director of the project and cofounder of Anansi Health, a nonprofit whose mission is to help organizations launch CHW programs. New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene is following a similar tactic, hiring CHWs to help public housing residents manage their health conditions.5

Reducing Barriers to Integrating CHWs

If CHWs are able to help complex—and expensive—patients in ways that other health care professionals sometimes can’t, why are they not more commonly included in health care teams? Not surprisingly, one major reason is funding. Many CHW programs are grant-funded and tend to end when grants do. Several states are now using State Innovation Model grants from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to support CHWs’ work. Such efforts are likely to provide an important evidence base on their impact—but it’s uncertain whether they will lead to longer-term commitments.

There are a few avenues to secure public funding for CHWs. Some states, including New York, Oregon, Minnesota, and Massachusetts, have used Medicaid waivers to reimburse CHWs. And the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced that states can be reimbursed for using CHWs to deliver preventive care services—although there has been limited take-up of this rule, in part because of the need for states to file detailed plan amendments.

Need for Standards on Training and Scope of Practice

Another set of concerns relates to uncertainty about how to train CHWs and how to define their scope of work. Some states require CHWs to gain formal certification, but there is wide variety among the curricula and standards. For instance in Ohio, Matos notes, CHW certification is governed by the board of nursing—leading to requirements that CHWs take courses on topics such as anatomy and physiology that are more appropriate for nurses. “This type of training is not relevant to their practice,” he says.

Nell Brownstein, who spent 25 years working on CHW programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is now an adjunct associate professor at Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health, is taking part in a national effort to develop recommendations on CHWs’ scope of practice and core competencies to inform training curricula and practice guidelines. “Because the most troubling thing to me is people reinventing the wheel and each group coming up with its own curriculum,” she says.

Training programs should include information on HIPAA, motivational interviewing, how to work with clinicians, and public speaking as well as some information on lifestyle risk factors, behavioral health problems, and disease-specific information, among other topics, Brownstein says. Having national standards on what CHWs can do and what they need to know to do it should promote greater understanding of their work and how it aligns with health system goals.

In defining CHWs’ scope of practice, it’s important to preserve their unique identity, advocates also say. “They are not low-paid replacements for office workers or clinical staff,” Brownstein says. It’s also important to train clinical staff on what CHWs do and how to take advantage of their work. Otherwise, it’s easy for them to become marginalized in clinical settings.

Some CHW competencies go beyond training, and must be identified in recruitment, says Matos, noting that employers tend to look for “the stuff your momma gave you: honesty, integrity, commitment, and compassion.” And while it’s not crucial CHWs come from the same neighborhood or share the same language as the patients they serve, “life experiences, beliefs, norms, and shared socioeconomic backgrounds” drive their relationships, he says, describing a Latina CHW who was able to form a bond with a Pakistani family as a result of their shared experiences as immigrants.

Looking Ahead

Finding a place for CHWs on care teams will require more leaders to understand the value CHWs bring, says Hong, something that may be aided by the experience and lessons learned through large-scale efforts such as those ongoing in Los Angeles and New York. A lot of what has happened to date has been driven by the grassroots CHW movement, he says, noting that a “tipping point” will come when health system leaders say, “this is what we need.”

This also will require ensuring there are financial incentives to promote their use. ACOs may help if they demonstrate that CHWs offer a sustainable strategy for containing costs. And with an influx of newly insured patients and a shortage of primary care clinicians, leaders may recognize that CHWs can extend providers’ capacity to meet their patients’ needs, particularly for support in accessing social services and managing chronic conditions.

“New care structures such as ACOs and medical homes are going to be under considerable pressure to improve the quality of communication between providers and patients—the continuity and honesty of it,” says Carl Rush, principal of Community Resources, which provides policy and training assistance to CHW programs. “This is a key way in which CHWs can add value.”

1 Community health workers are much more common in low-income countries, where they are used to make up for shortages of medical professionals by performing public health and some clinical functions, such as vaccinations.

2 Community Health Workers National Workforce Study, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, March 2007. By contrast, there were an estimated 560,800 medical assistants working in the U.S. in 2012, with 29 percent growth expected in the profession over 2012–22. See http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/medical-assistants.htm.

3 The American Public Health Association’s 2009 policy statement defines CHWs as follows: “Community Health Workers (CHWs) are frontline public health workers who are trusted members of and/or have an unusually close understanding of the community served. This trusting relationship enables CHWs to serve as a liaison/link/intermediary between health/social services and the community to facilitate access to services and improve the quality and cultural competence of service delivery. CHWs also build individual and community capacity by increasing health knowledge and self-sufficiency through a range of activities such as outreach, community education, informal counseling, social support and advocacy.”

4 S. Findley, S. Matos, A. Hicks et al., “Community Health Worker Integration into the Health Care Team Accomplishes the Triple Aim in a Patient-Centered Medical Home: A Bronx Tale,” Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, Jan.–March 2014 37(1):82–91, http://www.chwnetwork.org/_templates/80/a_bronx_tale.pdf.

5 See http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2014/pr013-14.shtml. Implementation of the program has been slow and troubled because of the recent firing of a nonprofit hired to do the work. See https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2015/11/24/new-york-city-terminates-community-health-contract-with-troubled-nonprofit/.