Several large health systems are using community benefit dollars and money from community investment funds to reach beyond the walls of their institutions and address the upstream determinants of health—including access to safe housing, healthy food, and employment.

To retain their tax-exempt status, private nonprofit hospitals—which make up roughly 60 percent of U.S. hospitals—have a legal obligation to give back to their communities.1 Most do so by providing free care to uninsured patients, making up for Medicaid shortfalls, offering medical training, or sponsoring disease awareness campaigns and health fairs—all of which can be declared as “community benefit” on tax returns. A small minority are going beyond this, devoting revenues and portions of their investment portfolios in innovative ways intended to address the upstream determinants of health, including lack of access to healthy food and safe housing. The hospitals that have ventured into this area do so in part out of recognition that health is the product of much more than health care, with factors like poverty and education playing an outsize role.2 Most if not all are also mission-driven organizations or integrated delivery systems that have assumed financial risk for caring for large populations of patients.

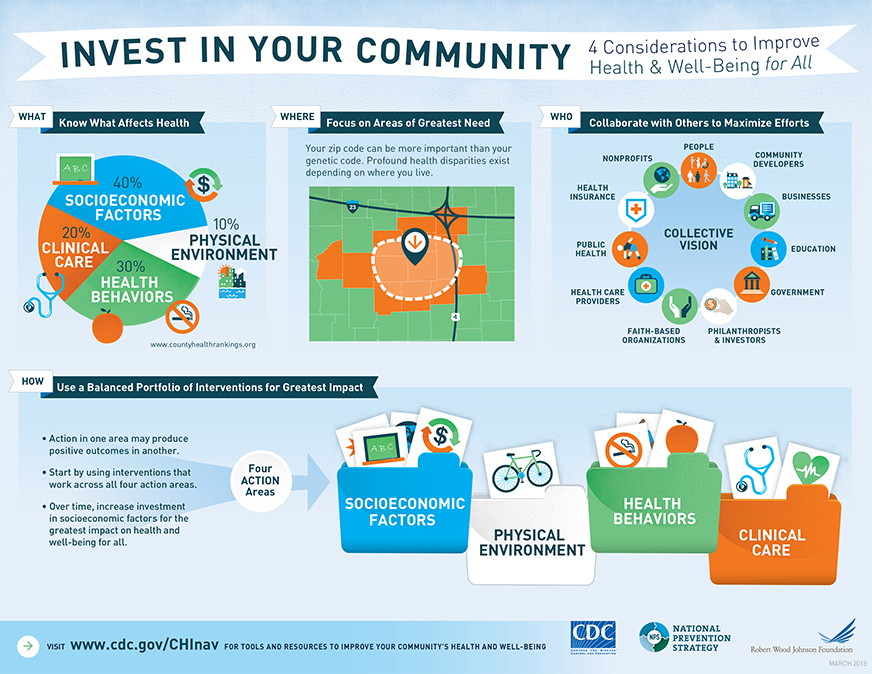

An Affordable Care Act provision requiring nonprofit hospitals to perform and publish triennial community health needs assessments may encourage others to follow their lead as the assessments shed light on what communities really need (see sidebar for more on community health needs assessments). These reports, sometimes conducted in partnership with public health agencies and organizations such as the United Way, highlight health inequities in so-called “cold spots”—the city blocks or neighborhoods that lack the clean environments, safe streets, good schools, vibrant economies, and other assets that support good health.3 They can also put firm numbers around an area’s most pressing health problems, such as high rates of obesity, suicide, and substance abuse.4

Graphic reprinted with permission from the CDC.

This issue of Transforming Care looks at how some nonprofit hospitals are leveraging their charitable dollars, community investment funds, and purchasing decisions to promote healthier behaviors and stronger communities, often in partnership with public health departments, schools, faith-based organizations, nonprofits, businesses, local governments, and others (see sidebar for examples of how hospitals have leveraged their purchasing power).

HEALTH SYSTEM PROFILES

Focusing on Hunger: ProMedica

ProMedica, a health system with 12 hospitals in Ohio and Michigan, allocates $100 million a year to community benefit spending and other charitable activities. One aim is reducing food insecurity in its hometown of Toledo, Ohio, where high poverty rates (as high as 40% in some neighborhoods) mean some residents struggle to feed themselves and their families, or subsist on cheap, unhealthy food.5

After the recent recession brought this issue into starker focus, ProMedica began screening all patients admitted to its hospitals for signs of food insecurity. Those who screened positive (about 4% of patients screened) were given a day’s worth of shelf stable food—much of it reclaimed from food banks—and referred to sources of nutritional support. ProMedica later integrated a two-question screen into its electronic health record system for outpatients as well (see box). “It’s helped to frame it for patients and doctors as a health issue, not a poverty issue, and the results revealed that you can’t recognize food insecurity by looking at somebody,” says Stephanie Cihon, associate vice president for community and government relations. “Many of our patients are the working poor. They have jobs, but aren’t making enough to pay bills in their entirety and we’re seeing food is something that gets sacrificed.”

| ProMedica’s Food Insecurity Screening Tool

Patients are considered to be at risk for food insecurity if they answer that either or both of the following two statements are “often true” or “sometimes true”:

|

To address this, ProMedica opened two “food pharmacies” in 2015 and 2016, where patients deemed to be food insecure are now referred by their primary care physicians. Staff dietitians offer patients counseling about appropriate food choices, taking into account their social circumstances (for example, whether they have a refrigerator and a working stove) and their medical conditions. Patients are then free to choose their own items at no cost—most of the food is donated from a local food bank—and can return once every 30 days for six months before they need a new referral. “This is food as medicine,” Cihon says.

Also in late 2015, ProMedica opened a full-service grocery store in downtown Toledo, in an area that had been deemed a food desert by the U.S. Department of Agriculture after a large grocer moved out. Owned and operated by the health system, the 5,500-square-foot store is part of the health system’s Ebeid Institute for Population Health, which also offers nutrition and cooking classes as well as jobs for local residents. By offering the classes, ProMedica hopes to achieve better results than stores established in food deserts in Philadelphia and New York, where researchers have found poor residents tended toward less healthy food, either because it was cheaper or it was what they preferred.6

Listening to Residents: Bon Secours

In contrast to ProMedica’s narrow focus, Bon Secours, a Catholic health system based in Marriottsville, Md., has taken a multifaceted approach to address social problems. “If a community has high unemployment, low graduation, and high infant mortality rates, you have to weave those points together or you will have limited success in transforming health status,” says Ed Gerardo, director of community commitment and social investments.

The health system, which operates 20 hospitals in six states and participates in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, has made reducing poverty and its effects a central focus, beginning by paying its lower-wage workers roughly 30 percent more than the federal minimum wage, promoting education and financial counseling, and developing career tracks designed to move employees into higher-skilled and higher-paying jobs.

Its efforts to strengthen the poor communities surrounding some of its hospitals have focused on improving housing, access to jobs, and developing loan programs that help residents avoid predatory lenders. In Southwest Baltimore, an area with extensive social problems (as depicted in the TV show The Wire), the health system has built more than 800 units of affordable housing and converted another 640 vacant lots into green spaces.7 Other efforts include youth training and employment programs, a family support center, and financial literacy programs for residents. This work has been done in partnership with local businesses, churches, neighborhood associations, and residents. “We take a catalytic approach—we seek to be an enzyme to get people talking and work from there,” Gerardo says.

Gerardo says the system learned early on it was best to let communities take the lead in setting priorities. When staff at Bon Secours Baltimore Hospital first wanted to do something about the high crime rates and pervasive drug problem in its neighborhood, “we thought the answer would be police patrolling, more arrests,” he says. “But when we set up a few community conversations, people said ‘We don’t like the crime and drugs, but if you really want to do something get rid of the trash piles. We’re tired of rats climbing into our homes and biting our children.’” This led to cleanup initiatives that fostered relationships and laid the grounds for future work, a model the system has followed in other communities.

Targeting Housing: Dignity Health

Dignity Health, a San Francisco, Calif.–based health system that operates 39 hospitals and hundreds of care centers in 21 states, has used its community investment program as well as grant dollars to address social determinants of health. Like Bon Secours, it has made housing development one of its key focus areas. For instance, the system has donated unused buildings and vacant land for the development of affordable housing and provided low- and no-interest loans to nonprofits developing housing for families, seniors, and homeless individuals, in some cases using a supportive housing model that couples housing with medical and social services.

Since 1990, Dignity Health has given a total of $62 million in grants and made $166 million in loans and equity investments in nonprofit organizations that provide access to food, housing, health, and education in low-income and minority communities. In 2015, it established a “social innovation partnership grant program” that offers grants (ranging from $100,000 to $250,000) to organizations to pursue or promote new models of care and other strategies for improving access, care coordination, and health outcomes for disadvantaged populations. The program has been used to convene housing developers, social service agencies, philanthropists, and government agencies that want to collaborate in building supportive housing models.

Direct Support and Policy Advocacy: Trinity Health

In November 2015, Trinity Health, a large Catholic health system based in Livonia, Mich., announced its $80 million Transforming Communities Initiative. The program will offer a combination of grants, low- or no-interest loans, and technical assistance to six community coalitions in which local Trinity Health hospitals are partners. The health system aims to leverage existing resources and serve as a long-term partner by offering capital and other support to promote efforts related to reducing teen smoking and obesity.

Each of the coalitions will receive technical assistance from community development financial institutions (CDFIs), which are private entities that offer affordable loans to local businesses, low-income housing developers, and others who may have trouble securing capital. The CDFIs will help fledgling nonprofits and new businesses “bridge the gap between community health and community development,” says Bechara Choucair, M.D., senior vice president of safety net and community health.

Each of the coalitions will also receive support from Change Lab Solutions and Tobacco Free Kids, groups that promote policy changes such as raising the legal age for cigarette purchases from 18 to 21 or taxing sugary drinks.

Community Benefit vs. Community Building Activities

When it comes to community investments, the activities taken by ProMedica, Bon Secours, Dignity Health, and Trinity Health are in many ways the exception, not the norm. Most nonprofit hospitals still focus the lion’s share of their charitable giving on covering the costs of caring for the uninsured and making up Medicaid shortfalls—practices that arguably benefit the health systems as much as their patients.8 “I’d argue a big hunk of community benefit spending may go to bad practice management. That is, it’s being used to cover losses that come from not managing Medicaid spending well,” says John Whittington, M.D., lead faculty for the Triple Aim at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Community Health Needs Assessments

While some nonprofit hospitals have made a practice of assessing the health needs of their patients for years, a provision in the Affordable Care Act made this a required activity. Every three years starting in 2013, nonprofits have had to perform community health needs assessments—and publish their results (see Q&A with Kevin Barnett, Dr.P.H., M.C.P., who reviewed a subset of them). They also have to develop a strategy for addressing identified needs, though this does not need to be made public. Given the newness of these requirements, and many hospitals’ inexperience in thinking about public health, the results so far have been uneven. Jack Westfall, M.D., professor of family medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, says many assessments are superficial, relying on consultants to conduct surveys that don’t really get at underlying determinants of health. “If you go into a poor or rural community they will tell you they need a doctor, and more options for health insurance,” he says. “But if you actually sit at people’s kitchen table and spend time talking with them, what you learn is they need transportation. It takes time and close contact to find out what the real barriers are.” Some nonprofits are partnering with public health departments or other hospitals in their cities to broaden their efforts; for example, in Chicago 20 hospitals working in collaboration with the Illinois Public Health Institute fielded an assessment that asked about housing, community safety, discrimination, barriers to accessing mental health care, public transit, access to food, and other issues.

Still, Greg Paulson of Trenton Health Team, one of Trinity Health’s Transforming Communities Initiative grantee organizations, says that the process “doesn’t have to be overly engineered, overly structured, or resource intensive. You just have to go in with an interest in finding people where they are, asking the right questions, and listening to the answers.”

The way the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) distinguishes “community benefit” and “community building,” two categories of charitable activities that hospitals report to the IRS each year, also plays into allocation decisions. The IRS defines community benefit as financial assistance to cover the costs of care, participation in Medicaid and other means-tested public programs, community health improvement services such as improving access to services or enhancing public knowledge, subsidized health services, and research. By contrast, it defines community building as improvements to the physical environment, including housing; economic development activities; environmental improvements; leadership development and training for residents; coalition building; health improvement advocacy; and workforce development.

The IRS does not credit community building activities in the same way as it does community benefit work and the fact that it draws a distinction between the two gives hospitals pause. The American Hospital Association and others have been advocating for the IRS to clarify to hospitals that both categories of activities are legitimate undertakings—that in fact supporting things like stable housing or access to healthy food is supporting health—and that both will be considered by the agency when reviewing hospitals’ charitable activities. Hospitals are looking to make major investments in community revitalization but “want to be less at risk and to have greater clarity for reporting those investments,” says Maureen Mudron, deputy general counsel of the American Hospital Association.

Julie Trocchio, senior director of community benefit and continuing care at the Catholic Health Association of the United States, which provides guidance to hospitals on community benefit programming and reporting, says that while further clarification from the IRS can only help, existing guidance and instructions give hospitals more latitude that they may think. She says programs and activities--including those that fall in the community building category--can be reported to the IRS as community benefit as long as they are addressing a community health need and are provided to improve community health. “If that’s the case, it can be reported as community benefit—just so long as it’s not also reported as community building,” she says.

Investing for the Long Term

Another reason nonprofit hospitals may be reluctant to invest in community building is a concern about return on investment—in dollars or health outcomes. Denise Koo, M.D., advisor to the associate director for policy at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), says health system staff often ask the CDC for evidence of the financial impact of efforts to address social determinants. “They want examples to show their C-suite that people are saving per-patient costs or decreasing emergency department visits or decreasing admissions, especially if they are able to do it in the current fee-for-service environment. They want to be able to show it’s worth the risk,” she says. Hearing this concern from hospitals led the CDC to develop a community health improvement navigator, including tools for how to do the work and examples of interventions that have had some results, including financial impacts. And investigators with the National Institutes of Health–funded Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities describe some evidence of the health benefits of interventions focused on education, income enhancement, housing, among others here.

But even if evidence begins to emerge that better housing or safer streets improves people’s lives, it may still be difficult to tie those changes back to particular health outcomes. Jack Westfall, M.D., professor of family medicine at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, says that this may not be necessary since it has face validity that those who have a stable home, good nutrition, and safer neighborhoods are more likely to have good health. And it may take years, if not a generation, to demonstrate impact. “You have to be frank about the long-term nature of it. I’ve seen many people ‘sell’ activities to hospital boards, glossing over the time frame and a board scraps it within a year or two. You have to say we won’t be able to attribute returns to this in the next five years,” he says.

Gerardo agrees. One of the hardest things about this work is that “people often want results faster than they can be achieved,” he says. He feels fortunate that Bon Secours’ leaders see it as generational work. That may be the best way to position it, he says, by asking executives “what do you want to be remembered for?”

Leveraging Purchasing Power and Hiring

In addition to charitable investments and grants, large health systems like Dignity Health, Trinity Health, and Kaiser Permanente are leveraging their purchasing power to promote change. Such approaches may have more of a dramatic impact than community benefit or building dollars, given the amount of money involved.

Hospitals are often among the largest employers in their communities and they can do a lot to help poor residents and neighborhoods through strategic hiring as well as purchasing practices. John Whittington, M.D., lead faculty for the Triple Aim at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, notes that hospitals can procure supplies and hire contractors that are owned by and/or employ local residents, build in underserved communities, and pay higher wages to their own staff, among other activities.

When, for example, Cleveland’s University Hospitals system set out to build five new medical facilities in 2005, it set specific goals related to hiring businesses owned by minorities and women and directing its spending toward businesses based in the region. After five years, they met three of their four goals.. The system has now enshrined these practices in its purchasing policies.

Other systems, including Children’s Hospital of San Diego and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, have for many years offered training and mentoring in the health professions to high school and college students in low-income communities—both to create more career opportunities for young people and to build the pipeline for health care workers.

Notes

1 In 2014 about 58 percent of the 4,926 U.S. community hospitals were private nonprofit entities. See American Hospital Association, Fast Facts on U.S. Hospitals, http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/fast-facts.shtml.

2 See, for example, R. Chetty, M. Stepner, S. Abraham et al., “The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014,” Journal of the American Medical Association, April 2016 315(16)1750–66; The Biology of Disadvantage: Socioeconomic Status and Health, Feb. 2010 issue of the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/nyas.2010.1186.issue-1/issuetoc; P. Braveman and L. Gottlieb, “The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes,” Public Health Reports, Jan./Feb. 2014 129(Suppl. 2):19–31, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3863696/; and L. McGovern, G. Miller, and P. Hughes-Cromwick, “Health Policy Brief: The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes,” Health Affairs, Aug. 21, 2014, http://healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief_pdfs/healthpolicybrief_123.pdf. It’s also important to note that the ACA coverage expansions have reduced the number of uninsured patients in recent years, and thus lessened the demand for charity care in many states. This trend may also have some effect on hospitals’ community benefit allocations in some cases.

3 For more on “cold-spotting,” see J. Westfall, “Cold-Spotting: Linking Primary Care and Public Health to Create Communities of Solution,” Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, May/June 2013 26(3):239–40. Westfall’s proposal builds on a framework laid out in a 1966 report by the National Commission on Community Health Services, Health Is a Community Affair, which was supported in part by The Commonwealth Fund.

4 Notably, hospitals do not have to disclose whether or how their community benefit spending conforms to what they find in the community health needs assessments. Nor do they have to report how their community benefit spending lines up with what they’ve said they’ll do to meet identified community needs in their implementation plans.

5 While living in poverty has many negative consequences, the effects are often exacerbated when many poor residents live in the same neighborhoods. In Toledo, 35 percent of the city’s 113,094 poor residents live in extremely poor neighborhood—where the poverty rate is 40 percent or greater. The metro area’s concentrated poverty rate was 24 percent during the recession. The 11 percentage point increase in concentrated poverty was one of the greatest of any major metro area since the recession. Toledo’s extremely impoverished neighborhoods were mostly clustered in the southeast during the recession. Since then, extreme poverty has spread southward across the Maumee River into East Toledo. See http://247wallst.com/special-report/2016/04/26/cities-hit-hardest-by-extreme-poverty/4/.

6 M. Sanger-Katz, “Giving the Poor Easy Access to Healthy Food Doesn’t Mean They’ll Buy It,” New York Times, May 8, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/09/upshot/giving-the-poor-easy-access-to-healthy-food-doesnt-mean-theyll-buy-it.html?_r=0. For more on ProMedica’s approach, see T. Hussein and M. Collins, “The Community Cure for Health Care,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, July 21, 2016, http://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_community_cure_for_health_care.

7 D. Zuckerman, Hospitals Building Healthier Communities: Embracing the Anchor Mission, Democracy Collaborative, March 2013, http://democracycollaborative.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/ExcerptHospitalsBuildingHealthierCommunities-BonSecours.pdf.

8 In 2011, financial assistance and Medicaid shortfalls accounted for 55 percent of all community benefit spending according to the IRS in its 2015 Report to Congress on private tax-exempt hospitals. Hospitals allocated the remainder across all other community benefit activities. IRS figures also show that in 2011, hospitals allocated slightly less than $2.7 billion out of nearly $62.5 billion in community benefit spending to community health improvement. See S. Rosenbaum and B. Choucair, “Expanding the Meaning of Community Health Improvement Under Tax-Exempt Hospital Policy,” Health Affairs Blog, Jan. 8, 2016, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/01/08/expanding-the-meaning-of-community-health-improvement-under-tax-exempt-hospital-policy/. A study of hospitals’ community benefit expenditures during the 2009 tax year found that while hospitals on average spent about 7.5 percent of their operating revenues on community benefit activities, less than 0.5 percent were allocated to community health improvement activities for which there is no expectation of payment. See G. J. Young, C.-H. Chou, J. Alexander et al., “Provision of Community Benefits by Tax Exempt U.S. Hospitals,” New England Journal of Medicine, Apr. 18, 2013 386(16):1519–27.