This inaugural issue of Transforming Care examines efforts to align physician incentives with the organizational goals of health systems and provider groups that have entered into contracts that reward them for delivering high-quality, cost-effective care. These organizations’ early experiences suggest ways of surmounting the challenges that often arise in designing incentive programs — including how to prioritize and streamline the many measures that payers use to define quality and value and how to deploy nonfinancial incentives to motivate behavior.

As health care organizations take on contracts with insurers that reward them for providing high-quality care and controlling costs, they must align their new organizational priorities with the incentives they offer providers. After all, it’s the many decisions frontline providers make daily that add up to the cost and quality achieved by health systems.

Doing so is no easy task, particularly for organizations that still receive the majority of their revenue from fee-for-service payments, which create compelling and competing incentives to pursue volume and provider productivity at the expense of other goals. There’s also little agreement on the most effective way of motivating physicians: Is money best in some situations? Or is it more effective to appeal to physicians’ professionalism, their desire for mastery, and their competitiveness?1

This issue of Transforming Care reports on health systems and provider groups that are working to answer these questions by testing approaches that differ from traditional pay-for-performance programs, which have had mixed results to date.2 The new compensation approaches seek to engage physicians in providing high-value care by, for example, creating incentives for them to proactively manage their patient panels, collaborate with others, and attend to the costs of care.

For these value-based payment approaches to succeed, physicians must be on board. “A lot of provider organizations entering into new value-based arrangements are not doing anything to change how they compensate their employed providers,” says Michael Bailit, president of Bailit Health Purchasing, a Massachusetts-based consulting firm. “It isn’t hard to see how such a misalignment will create a performance problem. Say an organization is assuming financial risk for the total cost of care and yet paying employed physicians in a manner that rewards them for increased volume of services: you’ve got a problem.”

Early Experiments

Organizations are incorporating measures of value into their physician compensation programs in a wide variety of ways, says Bailit, who with colleagues interviewed leaders of 16 health systems that had recently changed their physician compensation packages. He found no two approaches were the same: some relied on specific measures of value that they imposed systemwide, while others created a menu of measures and let physicians or departments choose. The proportion of physician compensation linked to measures of value also varied considerably, ranging from 10 percent to 60 percent.

Bailit found the measures used to assess value generally fell into six domains: clinical quality/patient safety, patient satisfaction, access to care, citizenship (e.g., through participation in an organization’s governance), efficiency, and use of health information technology. But measures of productivity remained important, too. “Organizations seem to be trying to counterbalance longstanding incentives to do more in order to earn more with value-based measures and incentives,” Bailit says. “It’s a balancing act.”

Getting the Formula Right

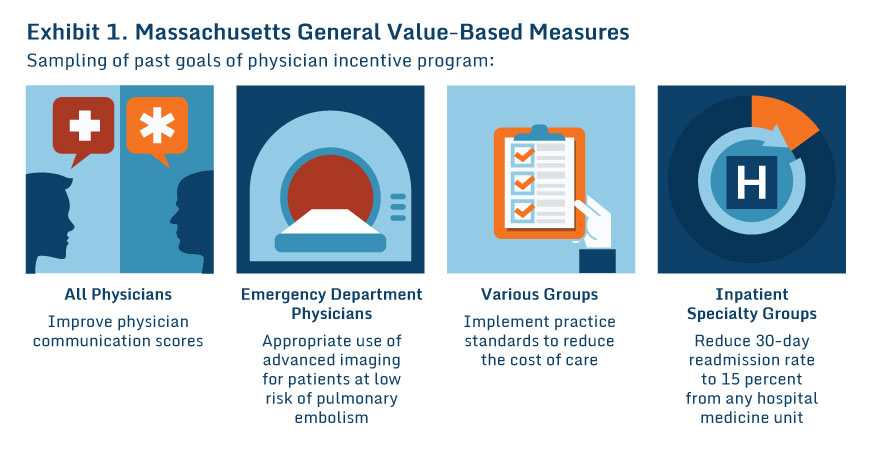

Finding the right number of measures can be tricky. Some organizations choose just a few in an effort to make them more salient to providers. Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, which receives about 40 percent of its revenue from risk-based contracts, selects just three measures for its physician incentive formula, changing them twice a year. One or two are designed to focus all physicians on shared goals, such as medication reconciliation, while the remainder are selected by each department (Exhibit 1).3 (Physicians who meet the targets are eligible for bonuses up of to $5,000.)

But other leaders say you can’t achieve widespread change by focusing on just a handful of items. Chicago-based Advocate Physician Partners, a joint venture between Advocate Health Care and about 5,000 independent and employed physicians, uses 170 different measures to assess care quality and value in its incentive program (up from 35 nearly a decade ago), with different measures for different specialties. Rather than adopting these measures from payers, the organization established its own set, which payers agreed to adopt and review annually.

“This gets rid of a lot of confusion and duplication,” says Pankaj Patel, M.D., senior medical director of Advocate Physician Partners. “Perhaps more important, when we give feedback to physicians, we give it based on performance related to the majority of patients in their practice—not just slivers based on patients in individual insurance programs. They get much more robust, meaningful feedback.”

As Advocate Physician Partners took on more value-based contracts in recent years (they now represent nearly three-quarters of its business), it altered the formula it uses to assess what it calls the “value contribution,” of each physician. Not only does the formula assess physicians’ clinical performance, it also takes into account the volume of patients they treat, and the degree to which they coordinate their care (measured by the extent to which care is provided within the network and how effectively physicians link patients with care managers).

“So it is no longer how well did you do with your diabetic patients in terms of sugar control and so forth, but how well did you do on all of our performance measures and how many patients are you managing and how well are you coordinating their care,” Patel says.

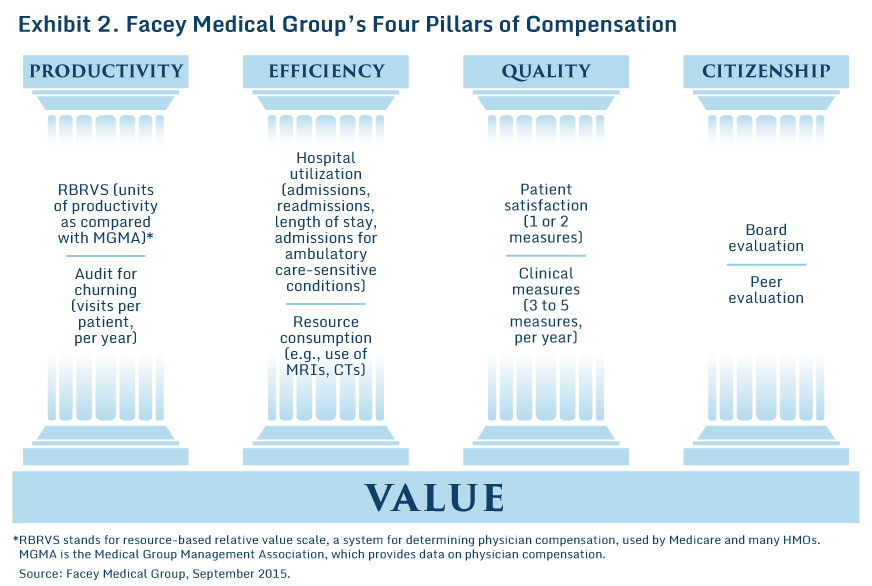

Facey Medical Group in Southern California, which has capitated, risk-based contracts for two-thirds of its patients, aims for the middle ground between “death by a thousand measures” in the words of its CEO, Bill Gil, and having too few to matter. To assess clinical quality and value, the medical group (which is affiliated with Providence Health and Services), selects three to five measures for each specialty each year, focusing on those for which there is significant performance variation and ample numbers of patients affected. Its overall compensation formula takes into account productivity, efficiency, and citizenship, as well as clinical quality (Exhibit 2).

Implementing Effective Reward Systems

While health systems and provider groups are working to develop compensation formulas that are both meaningful to providers—with measures of clinical quality and value they believe are fair and have an ability to influence—and useful for making comparisons, they are also experimenting with ways of reporting performance and rewarding providers.

Minnesota’s Fairview Health Services, which replaced its fee-for-service compensation model for primary care providers with new incentives based on measures of productivity, quality, patient experiences, and costs in 2011, tried something unconventional: rating clinicians (including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants) based mainly on the performance of their clinics, rather than as individuals, on the theory that population health management is a team sport. While this approach led to improved performance, researchers also found it greatly frustrated clinicians, who felt they had little control over their compensation.

Some organizations also are borrowing principles from behavioral economics in efforts to boost the effectiveness of physician incentive programs, including loss aversion—the idea that people are more motivated by the fear of a loss than the opportunity to gain. Massachusetts General used this principle when at the outset of its program it gave upfront incentive payments to physicians that were tied to working on certain metrics and goals in the future.

Partnering with University of Pennsylvania researchers, Advocate is testing the effects of several different approaches to reporting and rewarding physicians. It will test whether it’s possible to promote greater collaboration among providers by making half of a physician’s incentive payment dependent not on their individual performance, but on the performance of their physician–hospital organization—up from 30 percent now. It’s also testing the effects of giving providers continuous feedback on their performance through a registry of 1.4 million patients that’s updated daily. “Maybe when you give physicians real-time feedback they proactively manage their patients,” Patel says. “They don’t wait to the end of the year and do a mad dash to get all of their patients in for visits or needed labs.” Finally, Advocate is testing to see if framing the incentive as a potential loss rather than a gain has an impact on behaviors.

Beyond Financial Incentives

As organizations experiment with different compensation formulas and reward systems, they also must grapple with the vexing question about the best ways to motivate physicians: through extrinsic motivations such as financial bonuses, or intrinsic motivations such as the desire to help others or experience a sense of purpose or competence.

Results from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts’ Alternative Quality Contract—in which physician groups that achieved savings and met quality targets received substantial bonuses—suggest that financial incentives are not always essential to changing physician behavior. Some of the successful groups shared the funds with individual physicians, but some didn’t. “The physician incentive model wasn't consistent at all across the groups,” says Robert E. Mechanic, M.B.A., senior fellow at the Heller School of Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University and one of the program's evaluators.

It may be that it’s hard to use money as an effective signal to cut through the noise of physicians’ busy work lives. Many physicians have complicated reimbursement packages (with some receiving purely fee-for-service compensation while others are paid through a blend of salary as well as bonuses for meeting productivity or other targets)—making it harder to discern changes. A national survey found that one of six doctors didn’t even know whether they were eligible for performance incentives.4

Public reporting of comparative performance data, for example through a website, is another approach to influencing physician behavior, and experience from the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality suggests it can be a powerful motivator to change.

Some suggest that appealing to physicians’ desire to serve patients and deliver the best possible care may be the strongest motivator. Amol Navathe, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of health policy and medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, points out that a “physician acts as an agent first and foremost for the patients—making decisions and recommendations on their behalf. That is very powerful in differentiating how physicians are influenced compared to other workers.”

The Choosing Wisely campaign, which seeks to reduce the use of wasteful or unnecessary medical procedures, has gained traction by appealing to physicians’ professionalism (the lists of recommended procedures to question are created and promoted by several different medical specialty societies). Researchers at Weill Cornell Medical Center are seeking to build on this work by testing whether use of public commitment contracts—which have helped people achieve personal goals like losing weight or quitting smoking—can work in a professional environment by encouraging physicians to stick to their goal of avoiding delivery of low-value care.5

Of course, changing physician behavior requires more than just paying them fairly and well or offering strong motivations—successful health systems offer training and support to ensure providers are able to focus on managing patients’ care. Mechanic notes four factors that need to be in place to change behavior: a culture focused on improvement, data tracking to measure performance and feedback information to physicians, systems to help providers identify and resolve care gaps, and finally financial rewards. “It is important to have a financial signal so that clinicians know what the organization values, but groups need to have these other supports in place as well,” says Mechanic. “You can’t just have financial rewards and nothing else.”

Lessons and Next Steps

In spite of the uncertainty about the best ways to align physician compensation with health care organizations’ embrace of value-based care, there are some clear lessons emerging from their efforts thus far.

First, leaders need to include physicians in the development of compensation strategies and auditing systems and then proactively educate physicians about how changes in their compensation are aligned with the organizations’ strategic and financial goals. “Early adopters recommend a shadow period before officially altering compensation to inform physicians and administrators of the potential impact, allow time for modifications, and reduce anxiety,” says Mary Beth Dyer, a senior consultant with Bailit Health Purchasing. Facey Medical Group gives new physicians a three-year “incubation period” before adjusting their pay based on performance.

It’s also important to reduce the time between measuring and reporting performance, and between reporting performance and rewarding incentives (or vice versa, if upfront payments are used). Providers and payers also should work toward alignment on how to assess “value” in health care. As they do so, they should strive to develop assessments based not on expediency but on meaningful and actionable measures of care quality, efficiency, and outcomes. In particular, efforts should be made to include patient-reported outcomes in physician assessments.

Aiming for full transparency around incentives—though it can be painful—also may be important. “I want all doctors in our system to know what every doctor made—and to see that superstar performance is rewarded significantly higher,” says Gil, noting that doctors can handle knowing there are winners and losers.

Notes

1. While some organizations have begun to offer new incentives to nonphysician providers such as nurse practitioners, nurses, and physician assistants, most efforts target physicians. For this reason, we have focused this issue on physicians.

2. For discussion of the mixed results of pay-for-performance programs, see S. Woolhandler and D. Ariely, “Will Pay for Performance Backfire? Insights from Behavioral Economics,” Health Affairs Blog, Oct. 11, 2012.

3. D. F. Torchiana, D. G. Colton, S. K. Rao et al., “Massachusetts General Physicians Organization’s Quality Incentive Program Produces Encouraging Results,” Health Affairs, Oct. 2013 32(10):1748–56.

4. K. L. Ryskina and T. F. Bishop, “Physicians’ Lack of Awareness of How They Are Paid: Implications for New Models of Reimbursement,” JAMA Internal Medicine, Oct. 2013 173(18):1745–46.

5. Some researchers have found commitment contracts can influence physician prescribing. See D. Meeker, T. K. Knight, M. W. Friedberg et al., “Nudging Guideline-Concordant Antibiotic Prescribing: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” JAMA Internal Medicine, March 2014 174(3):425–31.