Physicians are proposing new ways of delivering and paying for care that take aim at a key shortcoming of the nation’s fee-for-service system: lack of payment for some high-value services. Their condition-specific models encourage adherence to evidence-based guidelines and reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and testing that has little benefit. Finding payer support for these models has proven challenging for some despite evidence of cost savings or improved health outcomes.

With the share of the nation’s gross domestic product devoted to health approaching 20 percent and a tsunami of aging baby boomers closing in, it’s clear the United States needs to find creative ways to curtail health care spending. Unfortunately, many such efforts led by payers and policymakers — including pay-for-performance, accountable care, and bundled payment programs — have produced only modest savings.

Some physicians have taken up the challenge and put forth their own ideas to achieve greater value for health care dollars. Many leverage grant funding from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) and elsewhere to test their ideas. Some proposals come in response to Medicare’s call for ideas on how to move away from fee-for-service payment and promote high-value care. Their new care models take aim at common and costly conditions such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and musculoskeletal problems and seek to achieve savings by encouraging greater adherence to evidence-based guidelines, engaging patients in decision making, and avoiding complications that can lead to unnecessary care. Their condition-specific approaches could benefit patients who have frequent interactions with health care providers and may be vulnerable to complications from treatment.

Since December 2016, physicians — represented by physician groups, specialty medical societies, and others — have submitted 25 proposals to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC), which was created under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 and tasked with evaluating physicians’ ideas for new payment models.

There isn’t enough money to fund care delivery for aging baby boomers if we continue to treat patients tomorrow like we are treating them today.

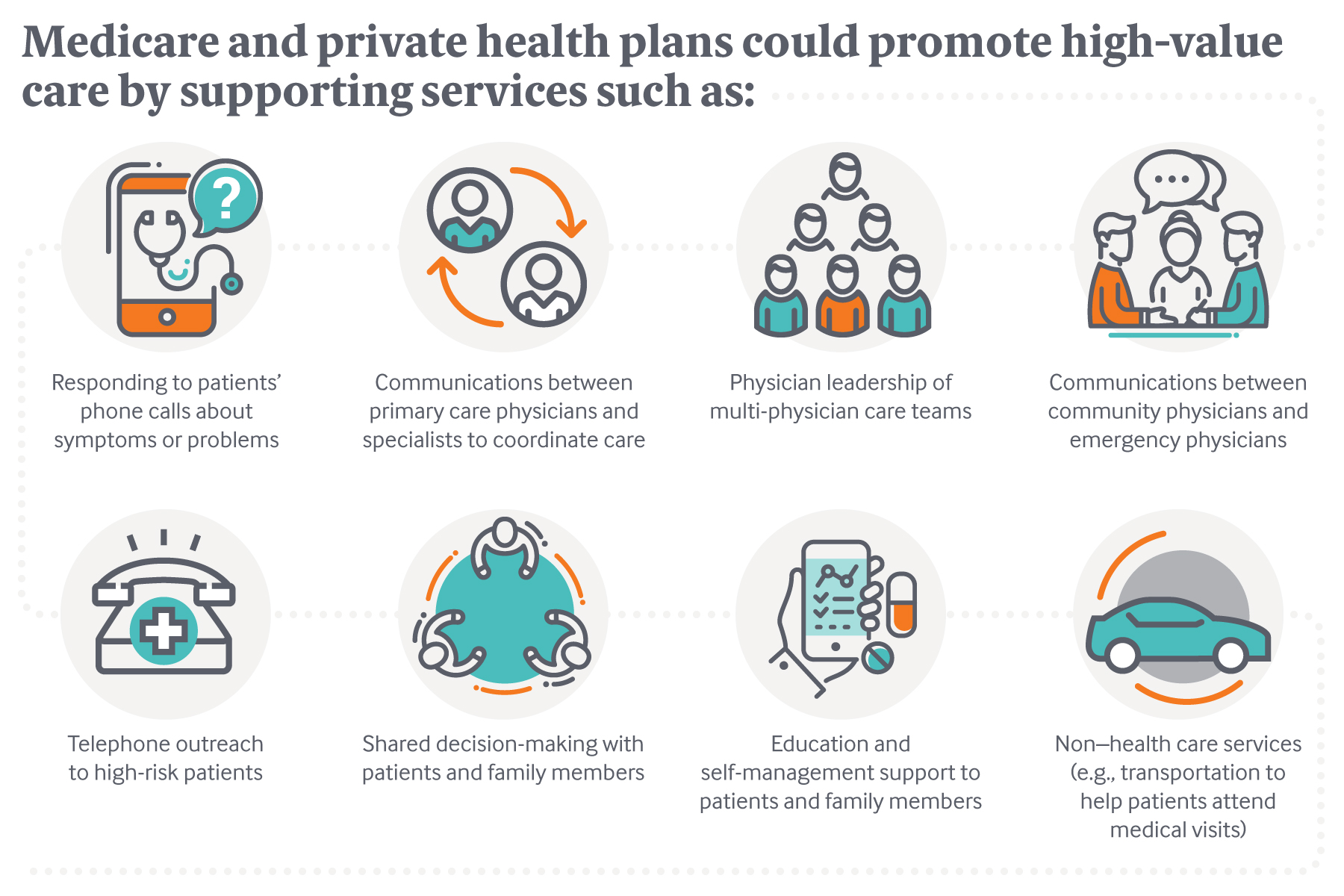

If eventually approved by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the alternative payment models would offer physicians per member per month fees, shared savings, or other payment methods to manage care differently. These and other value-based payment approaches would overcome two main hurdles to reforming care delivery under the fee-for-service system: lack of payment for services, such as hiring nurses to triage problems, that can improve health outcomes; and the potential loss of revenue to providers who help patients avoid unnecessary care.

The physician-proposed alternative payment models also seek to redress what some see as a shortcoming of bundled payments, which cap payment for an episode such as total joint replacement but don’t offer guidelines on what providers might do to reduce spending. And unlike global payment approaches, they offer new financial support for particular services — often simple, proactive steps — that are likely to produce downstream savings. “The path to higher-value care should start by asking physicians where they see opportunities to improve care and reduce costs and then paying them in ways that enable those changes to be made,” says Harold D. Miller, president and CEO of Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform and a member of the PTAC.

In this issue of Transforming Care, we look at new approaches to delivering and paying for care developed by physicians: some have been piloted through grants from the CMMI and/or submitted to the PTAC for consideration as new Medicare payment models, while others have gained support from private insurers or are being spread by physician entrepreneurs.

Engaging Patients in Shared Decision-Making and Avoiding Unnecessary Cardiac Procedures

Many people who go to their primary care doctor or cardiologist with complaints of periodic chest pain that might suggest cardiovascular disease end up receiving tests and interventions that are not in keeping with clinical guidelines, pose risks, and drive up costs.1

The Wisconsin and Florida chapters of the American College of Cardiology led a CMMI-funded pilot that brought together several decision support, patient engagement, and performance feedback tools in an effort to promote appropriate treatment for patients whose chest pain appears to be related to stable ischemic heart disease. The aim of the Smarter Management and Resource Use for Today’s Complex Care Delivery (SMARTCare) pilot was to reduce inappropriate stress tests and imaging (e.g., angiograms to view blood vessels in the heart) as well as reduce inappropriate percutaneous coronary interventions, an invasive procedure that carries risks of bleeding and other complications. It also sought to increase the number of patients who change their behavior to reduce their risks of developing severe heart disease.2

To achieve these goals, its developers embedded evidence-based guidelines into electronic health record systems at 10 cardiology practices in Wisconsin and Florida and leveraged them to guide decision-making at the point of care. The tools didn’t dictate treatment but instead helped physicians customize guidelines to make them relevant to their patients. “Some so-called decision support tools are really documentation support: if a doctor wants to order a stress test they have to supply a reason why,” says Thomas J. Lewandowski, M.D., a cardiologist in Appleton, Wis., and principal investigator of the SMARTCare pilot. “By contrast, the SMARTCare tools ask doctors to enter in a particular patient’s symptoms and then [the tools] map each to different indications, so it helps them verify whether what they’re doing fits with clinical guidelines.”

Physicians participating in the pilot also educated patients about their unique risk factors, engaged them in shared decision-making, and collected feedback on their care experiences. At the Medical College of Wisconsin, patients were shown an educational video explaining the risks and benefits of various cardiac procedures before meeting with a cardiologist. They also completed the Seattle Angina Questionnaire to assess their symptoms and severity (at other sites, patients completed the Heart Quality of Life questionnaire). Cardiologists drew on the survey data and videos to help patients understand their risks and options — putting some guide rails around what can be a highly charged conversation. Without information, “patients often push for more invasive procedures,” says Nicole Lohr, M.D., a cardiologist at Medical College of Wisconsin. “They say, ‘Doc, it’s my heart; you better do something about it because I don’t want to die.’”

The reality is most primary care doctors and even some cardiologists who order cardiac diagnostic tests don't always choose appropriate, evidence-based testing because of the time constraints within an office visit and a lack of exposure to changing guidelines.

Some SMARTCare participants also used the IndiGO tool, a simulation model that calculates a patient’s risk for having a heart attack or stroke based on their cardiovascular disease history, comorbidities, body mass index, and lifestyle behaviors. It then models the potential benefits of behavior changes (e.g., smoking cessation or weight loss) and medications. Cardiologists used the tool to encourage patients to make behavior changes and identify where they had opportunities to intervene. “Take a 75-year-old whose coronary disease, diabetes, and blood pressure are under control, and who exercises and does not smoke: there is nothing left to do with that patient to reduce their risk,” says Lewandowski. “But the role of IndiGO is to identify which patients have risk factors that we still have ability to affect. That is something that our current tools don’t do.”

Data on patients were collected throughout the course of treatment, enabling clinicians to benchmark their performance against peers and receive rapid feedback on health outcomes and costs.

The SMARTCare pilot was prompted, in part, by data from Wisconsin’s all-payer claims database showing wide variation in cardiology resource use, information that also caught the attention of the WEA Trust, a self-insured plan that covers 110,000 Wisconsin public employees. WEA Trust is now encouraging health systems to negotiate for payment to embed the system as a means of offsetting the revenue they may lose from avoiding stress testing, nuclear stress testing, and catheterizations. “Payment is a signal of what we value,” says Tim Bartholow, M.D., vice president and chief medical office at WEA Trust. “If we want better medical decision making, we need to increasingly focus payment on team-based decision making and more realistic, cost-based reimbursements for commodities such as imaging, laboratory tests, and drugs."

Heading Off Complications for Oncology Patients

In 2014, cancer care accounted for $87.8 billion of health care spending for noninstitutionalized Americans; of that, roughly 28 percent went to emergency department and hospital care. Barbara McAneny, M.D., a New Mexico oncologist and president of the American Medical Association, says a large portion of the hospitalizations and emergency department visits are to treat fevers, dehydration, and other complications of chemotherapy that could be avoided with closer management in outpatient settings, where patients typically receive chemotherapy infusions. Avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations may also prevent further deterioration, she says. “In addition to the risks of infections and bed sores, if you take someone who isn’t healthy and can’t rebuild muscle mass, and you put them in a hospital bed for a few days, they end up with less muscle tone and a reduced quality of life.”

The problem is that oncology practices can’t bill Medicare or most private insurers for services like educating patients on how to recognize warning signs or hiring a nurse to answer calls and triage problems. At the same time, patients may be reluctant to trouble physicians when they first notice symptoms.

Through a grant from CMMI, McAneny led a trial of an alternate approach. From 2012 to 2015, the Community Oncology Medical Home (COME HOME) tested whether providing advanced access to patients and closer care coordination could lead to earlier detection of problems and avoid hospitalizations. Seven cancer centers offered on-demand visits, including on nights and weekends, for emergent issues such as pain, dehydration, nausea, or fevers; hired a nurse to respond to patients’ question and triage problems; and implemented 37 unique care pathways for diagnosis, treatment, and symptom management of different types of cancers. “We make our triage pathways available, so people can figure out which patient with left-sided pain is having a heart attack and needs to go to hospital and which has bony metastasis and doesn’t need their fourth cardiac workup,” McAneny says.

An evaluation of the pilot found this approach led to significant reductions in emergency department visits and hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, as well as significantly lower average cost of care ($601 less per patient per quarter). McAneny says that practices that enabled nurses to execute standing orders to address patient complications achieved the most dramatic reductions in hospitalizations; at her own practice, hospitalizations were cut in half.

This February, McAneny submitted a proposal to the PTAC for consideration of an alternative payment model to support COME HOME, and 16 practices have agreed to participate, should it be funded. Notably, the practices have also agreed to share clinical and claims data to feed into a software platform that would be leveraged to create customized treatment plans for patients and offer real-time physician education and performance feedback. Eventually, the goal is to use this pooled data to cluster cancer patients according to their risks and disease severity, then compare variations in spending and outcomes in each of the clusters; such information could help Medicare and other payers develop appropriate alternative payment models.

“Right now, nobody has the ability to accurately predict costs for a cancer patient who has x, y, and z characteristics,” McAneny says. “Even if you have multiple patients with stage 4 colon cancer, some are going to cost a whole lot of money and some will cost much less. We hope to learn which factors make the difference and to identify things that are modifiable through better coordination or different types of care.”3

Improving Quality and Reducing Costs for Back Pain Treatment

Back problems are among the most common reasons people visit a doctor, leading to more than $47 billion a year in medical costs. A review of 10 years’ worth of medical visits for back pain found ample evidence of overtreatment: instead of starting with anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy, as recommended by clinical guidelines, physicians have increasingly prescribed narcotics, ordered imaging, and referred patients to specialists. Overuse of opioids, in particular, has fueled the epidemic of addiction.

Andrew Haig, M.D., a physiatrist (a physician specializing in rehabilitation) and active emeritus professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at the University of Michigan, thinks clinicians in his field are well positioned to manage back pain by serving as “midfield players”: given their expertise, they are better able than primary care clinicians to explore the many potential causes of patients’ suffering and may be less wedded to high-cost interventions, like surgery and injections.

In 2008, Haig partnered with the Michigan insurer Priority Health to test this approach: all patients who were referred by their primary care physician to a surgeon for back pain were first required to see a physiatrist. The health plan waived members’ copayments for this visit, and physiatrists were given a $50 bonus, on top of the visit fee, to help patients talk through options. “I hold up five fingers and say, ‘When you leave here you are going to put something in your shopping cart: surgery, injection, pills, some kind of therapy, or doing nothing,’” Haig says. Without such guidance, patients may hold out hope there’s a magical solution to their problem. “It’s important for patients to leave with a finite sense of their options,” he says.

Over two years, Priority Health saw a 25 percent reduction in spine surgery among its members, as well as a 12 percent reduction in overall spine-related costs per member per month and continued member satisfaction, compared with the year before implementation of this approach.

Haig has since developed and tested other parts of a continuum of back pain management and has spun off a consulting firm to encourage providers and health plans to adopt the “Operation FastBack” model.

Under Operation FastBack, all patients with chronic back pain, for example, would be screened by a physiatrist. Those whose pain does not appear to be related to a serious medical condition (e.g., cancer) would then receive a multidisciplinary team assessment that can consider the wide range of factors and available treatments. Haig’s research found that psychological factors like depression, fear, and avoidance, as well as poor physical conditioning, are common among patients with back pain. The team includes a physical therapist to consider anatomical issues; an occupational therapist to explore how disability affects people’s lives; an exercise specialist to explore the role of physical conditioning; a psychologist to consider contributing psychiatric factors; and a representative for complementary/alternative medicine to consider such therapies. After their initial assessment, the team would work with a physiatrist and the patient to develop a holistic care plan. In a trial of 500 patients who underwent these team assessments, 17 people who received one type of complex intervention (functional restoration) had less work disability, fewer diagnostic tests, and fewer surgeries than those who were recommended this treatment but did not receive it.

Haig is now working with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Vermont to develop the infrastructure to support this model, starting with creation of a hub at one hospital that has the full staff and other resources to assess back pain patients, treat the ones with the most complex needs, and refer others to treatment at local clinics. Hub clinicians also would support the local clinics in providing best practice care in three regional emergency departments and primary care settings. Haig and Blue Cross and Blue Shield are tracking expenses and outcomes under this approach, with the goal of modeling how a bundled payment might support it.

Evidence-Based Prescribing to Control Costs for Rheumatoid Arthritis Treatment

Rheumatoid arthritis plagues some 1.3 million Americans with chronic joint pain and other problems. While biologic drugs have helped many patients who don’t respond to other types of medication, their price is much higher (around $50,000 a year) than traditional antirheumatic therapies (e.g., methotrexate, which can cost around $100 to $200 a year).3 This has raised concerns among some payers as well as patients, who may have to shoulder high copayments for a lifelong condition. Articularis Healthcare, which has 12 specialty rheumatology practices in South Carolina and Georgia, collaborated with a local insurer to develop a rheumatoid arthritis treatment pathway to ensure lower-cost medications are effectively tested before doctors recommend more expensive treatments.

Under the pathway, rheumatologists are prompted by their electronic health record system to follow American College of Rheumatology guidelines, which generally suggest an initial period of treatment with a traditional antirheumatic drug prior to escalating therapy to a biologic agent. The pathway also reminds physicians to periodically measure the effects of drug treatment on disease activity using a validated tool — another clinical guideline but one that may not be followed in all cases.

The “traditional medication is slow acting, and patients may not feel relief initially,” says Colin Edgerton, M.D., who practices at Articularis’s Low Country Rheumatology clinic, in Charleston. “A doctor may react to patients’ lack of relief and suggest switching to the biologic without really having a good metric built into the system to realize, ‘Oh, it’s only been six weeks. We should wait a bit longer to see if it can work.’”

Edgerton says this approach led to a 10 percent to 20 percent decline in the use of high-cost biologics, mainly achieved by identifying more patients whose conditions responded to the lower-cost medication. The local insurer pays Articularis a per member per month case management fee (around $500 to $1,000 a year) to defray the cost of staff required to implement the pathway and educate providers in its use; the two parties share in the savings that result from reduced use of biologic drugs.

Challenges to Spreading Physician-Led Alternative Payment Models

As these examples make clear, changing how care is provided and paid for in health care must begin by integrating new tools into electronic health record systems. This can be expensive and cumbersome; McAneny, for example, has struggled to enlist her electronic health record vendor in making changes needed to aggregate data across practices.

Those who are able to overcome technological challenges may find it hard to gain the attention and support of payers. While Medicare has called for new proposals, it has not yet acted on any of PTAC’s recommendations. Private payers have also been slow to support new care models. Edgerton, for example, has found it hard to enlist support from large national insurers for the rheumatoid arthritis pathway, perhaps because it has only been tested among a small number of patients. Banding together across practices, as is being proposed under the COME HOME model for oncology, could create the critical mass of patients needed to demonstrate efficacy for new care models and garner support from payers to invest in them.

Lewandowski says that Medicare could encourage multipayer support for initiatives like SMARTCare, thus ensuring that payers share equally in developing and testing new care models. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could also require accountable care organizations to pursue new approaches to high-cost specialty care, including orthopedics and cardiovascular care, rather than just meeting benchmarks on a relatively small number of performance metrics to qualify for shared savings, he says.

Brian Klepper, Ph.D., founding principal of Orange Park, Florida–based Worksite Health Advisors, a consulting firm that advises self-insured employers on how to find high-value clinical partners, says physician innovators often succeed by going directly to employers and offering them a financial guarantee of savings. “Like Amazon, they make people an offer they can’t refuse,” he says.

Perhaps most important, it will be crucial to enlist support for new care models from physicians; some may feel new decision support tools or care pathways are too prescriptive, while others may perceive a threat to their revenue stream from efforts to avoid high-cost services. But some of the models could make some physicians’ jobs easier. “Doctors are burning out in droves, and we can’t keep adding to their plate,” says John Mafi, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of medicine and health services research at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. “Making the right thing to do the easy thing is really the promising way to get real change to happen. It’s easier said than done.”