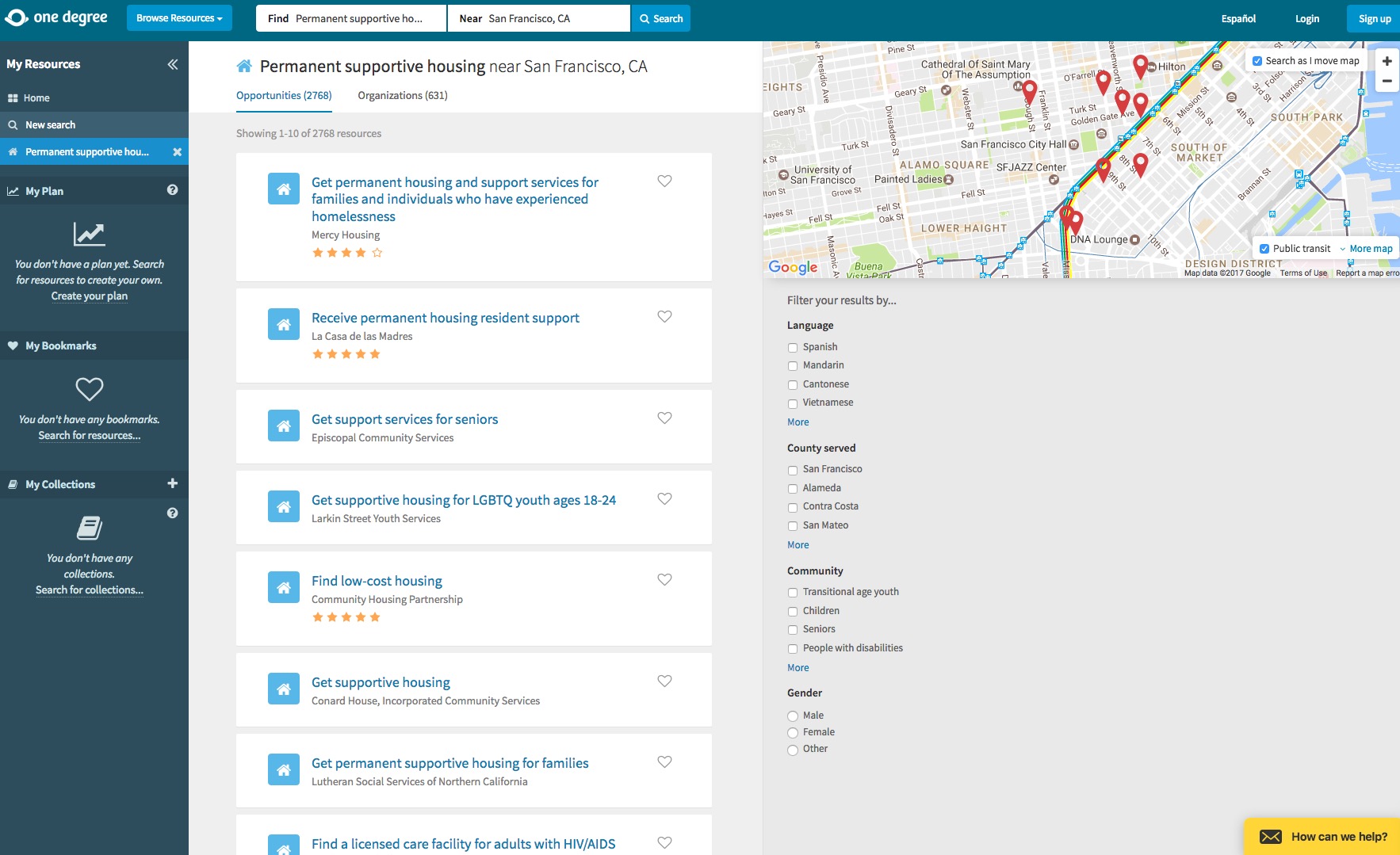

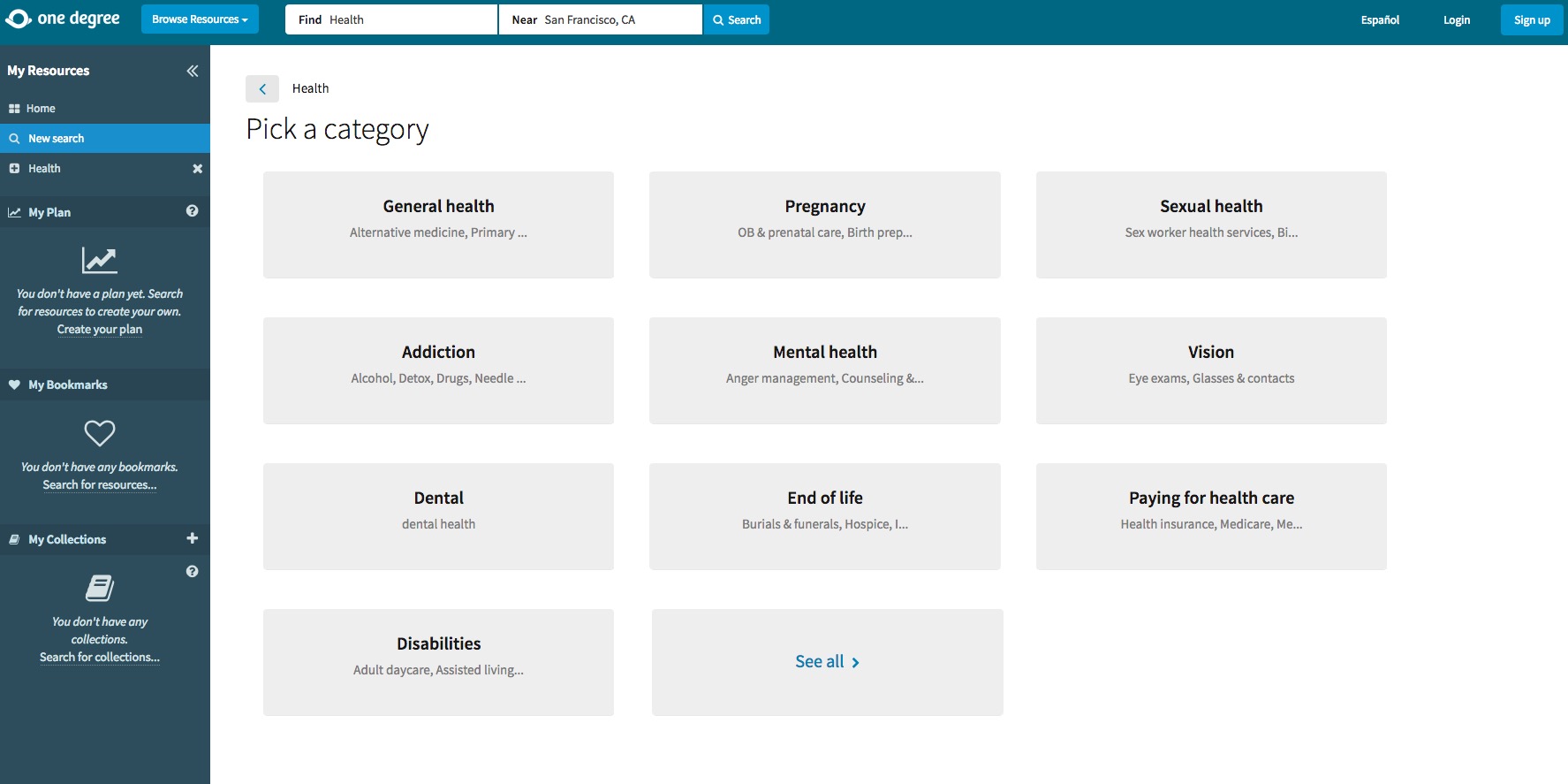

Providers like Cincinnati Children’s aren’t just screening patients for social and environmental risks; they’re also developing interventions and partnerships to mitigate them. Such efforts are driven by pressure to contain costs and are adding to a growing body of evidence showing that when people have stable housing, good nutrition, reliable incomes, and other material needs met, they have better health, as well as lower medical costs.4 In a companion story, we look at several digital tools that help providers find and share information with community partners.

Making Social Risk Screening and Referral Routine

The Los Angeles–based cancer center City of Hope developed a touchscreen system, SupportScreen, to ask patients about social or financial problems that may affect their ability to follow recommended treatment, as well as stress they may be experiencing related to their cancer diagnoses. According to Matthew Loscalzo, executive director of the center’s Department of Supportive Care Medicine, routine screening sends a message to patients that the cancer center wants to help with more than just clinical needs: “Just asking patients the questions opens the conversation and tells the person, if you have these problems, we can help.” Surveys among 35,000 City of Hope cancer patients found, not surprisingly, that low income is by far the strongest predictor of poor health outcomes, as well as of practical problems and distress—more important than patients’ race or marital status.

The center uses tablets to administer the screening rather than face-to-face interviews because it finds patients are more forthcoming that way—consistent with research on social screening tools.5 In addition to flagging potential issues, SupportScreen serves as a triage tool, immediately routing responses to appropriate team members (e.g., social workers, financial services staff, chaplains, and others) so patients can confer with them during their medical visits.6

Offering Guidelines for Conversations About Social Risks

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) have been early adopters of social risk screening because they serve many poor, uninsured, and otherwise vulnerable patients. Health centers in 44 states and many other provider groups are using the PRAPARE tool (short for Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences), which was developed by the National Association of Community Health Centers, Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, Oregon Primary Care Association, and the Institute for Alternative Futures to promulgate a standardized approach for documenting the many social risks faced by their patients and using that information to improve population health.7

In a pilot of PRAPARE involving seven FQHCs and three FQHC networks, center staff including nurses, community health workers, medical assistants, care coordinators, and others asked patients about their material security, transportation, housing security, stress, personal safety, social demographics, and other issues. Staff used the tool as a “guideline for conversation,” says Michelle Jester, research manager at the National Association of Community Health Centers, often using empathic inquiry, motivational interviewing, or other approaches to elicit patients’ trust. Most of the nearly 2,700 patients screened reported between four to seven risk factors; the greater the number, the more likely patients were to have hypertension.8

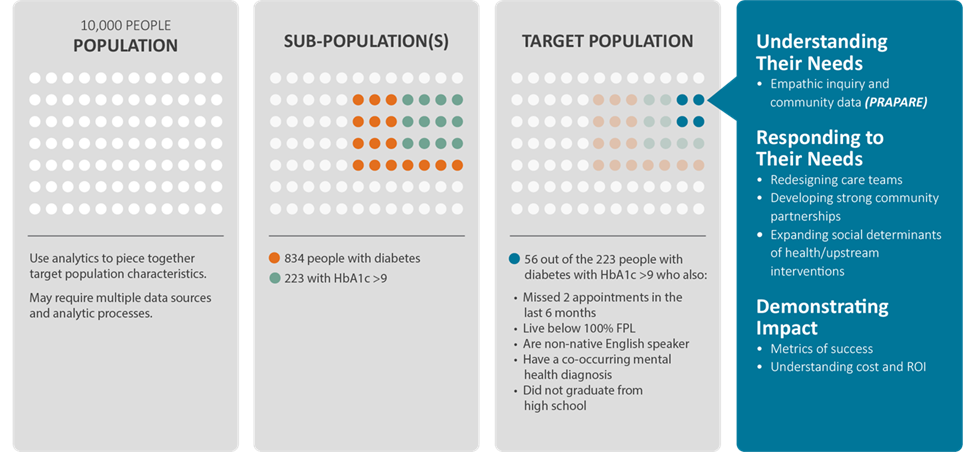

Starting with Subgroups of At-Risk Patients

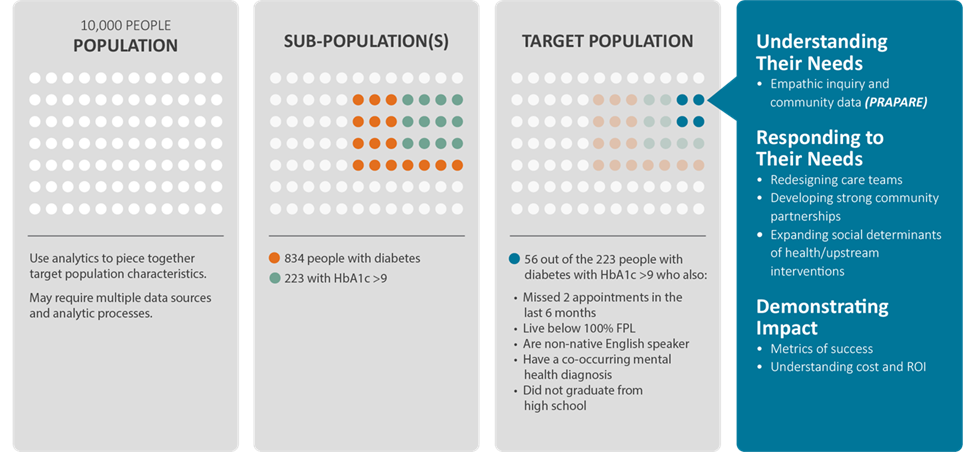

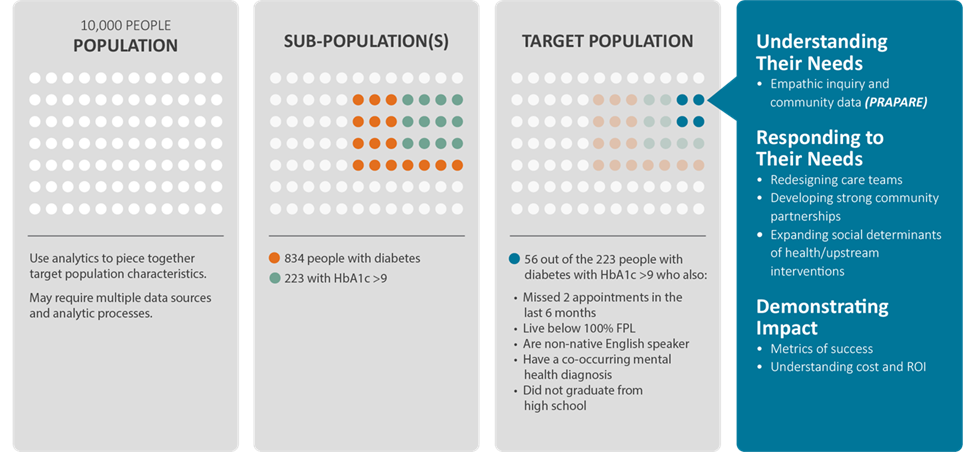

The Oregon Primary Care Association has been encouraging its member FQHCs to identify subpopulations of patients with unmanaged health conditions and use PRAPARE to figure out what nonmedical factors may be at play. This population segmentation work is part of a new Oregon Medicaid alternative payment model that gives clinics per member per month payments and, with them, the flexibility and incentive to address the social determinants of health. In some parts of the state, savings to Medicaid are already being redeployed to fund locally determined health improvement efforts.

Exhibit: Oregon Primary Care Association’s Population Segmentation Approach

© Oregon Primary Care Association 2017

For example, the Rinehart Clinic on Oregon’s far north coast began with 126 hypertensive patients. When interviews revealed most of these patients felt socially isolated, the clinic engaged them in a group wellness class. Many patients also admitted they lacked money to buy healthy food, and so the clinic created a partnership through which it can refer patients to a food bank. (The clinic has not yet tracked results of these efforts.)

Building Clinical–Community Partnerships

A common concern among those involved in the pilot was not being able to address the problems they found during screening. PRAPARE partners and health center staff determined that the most effective way to address this concern was to tell staff that “We won’t know what the needs are unless we ask. And hopefully documenting them will help us figure out which partners we should be working with,” says Jester.

The Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI)—a nonprofit research firm spun out of Dallas’s safety-net hospital, Parkland Health and Hospital System—created a citywide information exchange portal to facilitate such partnerships between health care and social service providers. The Dallas Information Exchange Portal is built to use diagnostic codes and natural language processing (which can, for example, capture clinicians’ notes about “noncompliant patients” or “missed appointments”) to gather information from electronic medical records that may indicate a nonmedical problem, such as lack of appropriate housing, food insecurity, or lack of transportation to medical appointments. With patients’ consent, providers use the portal to share relevant medical and social information with homeless shelters, food banks, and other nonprofits. The portal now includes information for over 200,000 Dallas residents and is used by 55 community partners.

Exchanging information about medical conditions and social risks has created a “no-wrong-door” approach for people looking for help, says Yolande Pengetnze, M.D., medical director at PCCI. For example, staff at a local food pantry—whom PCCI trained in how to support patients’ dietary needs—used the tool to help a woman with diabetes and high blood pressure choose appropriate groceries. When she confided to staff there that she had been having trouble scheduling a medical appointment and had stopped taking one of her medications because she couldn’t afford it, they were able to use the platform to connect her to Parkland staff who could help.

PCCI creates incentives for community partners to use the Information Exchange Portal by including case management tools that help them do their work. And, in a pilot, it made small payments (from $25 up to $200 per patient) to The Bridge, a Dallas homeless shelter, when they used the portal to help patients after hospital discharge by finding them short-term housing or transportation to follow-up appointments. There was a 40 percent relative reduction in emergency department visits among the 15 patients engaged in this way, compared with those not engaged.

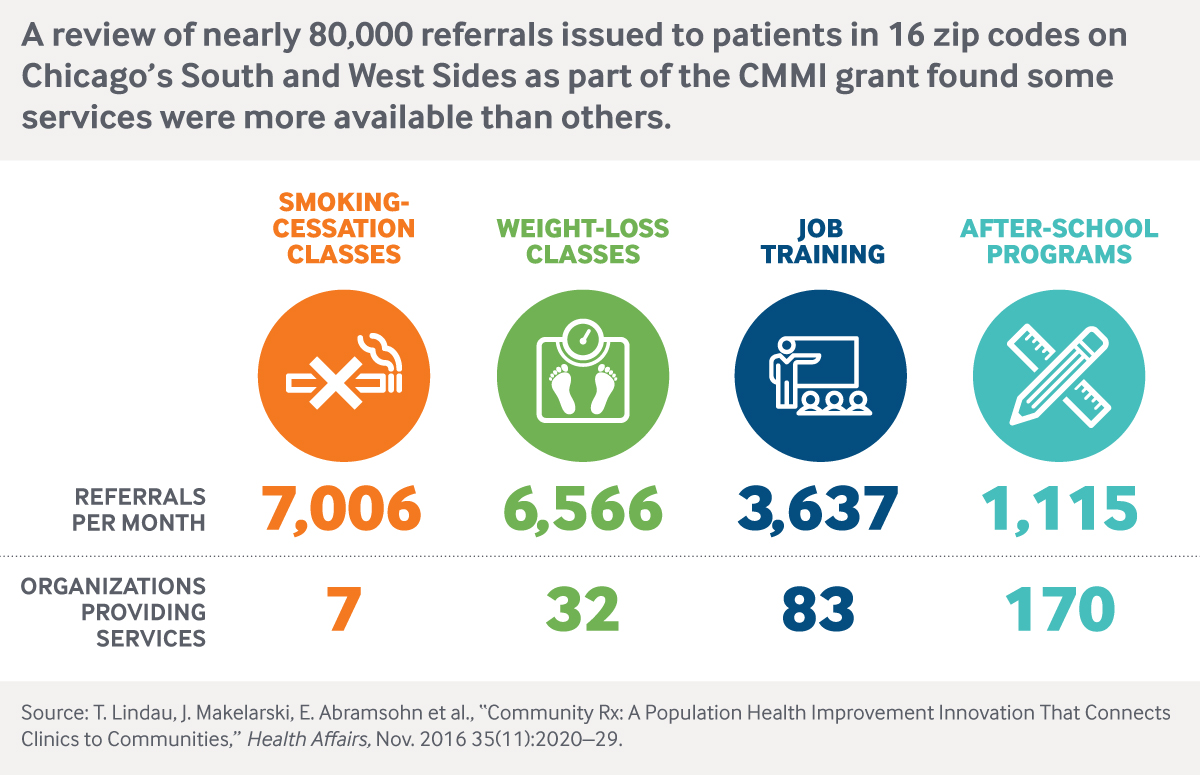

This May, PCCI was one of 31 sites to be awarded a grant from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation for the Accountable Health Communities Model—the first federal effort to test whether addressing people’s social needs impacts health care quality and expenditures. Along with Parkland, four other local health systems will be using the Dallas Information Exchange Portal to partner with 289 community organizations and Texas Medicaid.

Focusing on Patients’ Priorities

Along with these health system–led efforts, health plans are starting to attend to members’ social needs. Five years ago, when Dayton, Ohio–based CareSource—which operates Medicaid managed care plans as well as marketplace plans in five states—began enrolling newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries, their extreme poverty and other social challenges came to the fore. To figure out the best way to offer a hand and make their plans attractive to potential members, the health plan convened focus groups to explore one question: If we were to do one thing in addition to providing coverage that would have a significant impact on your overall health and well-being, what would that be? Overwhelmingly, people reported they wanted help finding good jobs.

In response, CareSource launched a Life Services program in its Dayton market, offering members the support of a coach to help them find training programs, apply for jobs, tap sources of child care and transportation, and take other practical steps. These services are coupled with health coaching when needed. Over two years in nine Ohio counties, coaches worked with 1,200 people, helping 450 secure full-time jobs and another 250 find training and educational opportunities. CareSource tracked a decrease in emergency department and hospital use among those receiving such help, as well as an increase in medication compliance. Based on these results, the health plan expanded the program to its Indiana and Georgia markets.

CareSource also received approval from Ohio and Indiana Medicaid agencies to add questions about members’ social and economic status—their educational level, employment, social supports, and other issues—in their health risk assessments. “A member might not be a smoker, might not have diabetes. But think of the 22-year-old mom with no GED, inconsistent housing, who doesn’t know what her next steps are,” says Karin VanZant, executive director of Life Services. “If we just had the usual health assessment, we’d put her in the healthy maternal category and stop outreach.” By intentionally asking about nonmedical issues, CareSource has a chance to “help that mom get her GED, find employment, and get on the path to sustainability,” she says.

Challenges and Early Lessons

As these examples make clear, there’s a great deal of experimentation as health care professionals partner with nonprofits to meet patients’ needs beyond medical care.

One prominent challenge in this work is that many circumstances mediate health: factors like income, education, housing, and nutrition that are highly correlated with health are also correlated with each other, making it difficult to discern which has the greatest influence and is most amenable to change.9 In addition, relevant risk factors may vary by condition: food insecurity may play a significant role in diabetes control, whereas exposure to violence may lead to behavioral as well as physical health problems. “To study it in a classic way is difficult. It would be challenging to do a randomized control trial to sort it out with so much variation in patients,” says Kahn.

Despite the challenges, there are efforts to build the evidence base, such as one led by University of California, San Francisco, researchers known as SIREN (Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network) that compiles and disseminates evidence of the effectiveness of social interventions and evaluation tools.

It’s also clear there are gradations of risk—some people have trouble affording rent, while others have nowhere to sleep most nights. That’s why it’s important to ask patients about the urgency of their need and let them select priorities, says Zach Goldstein, principal of innovation at Health Leads.10

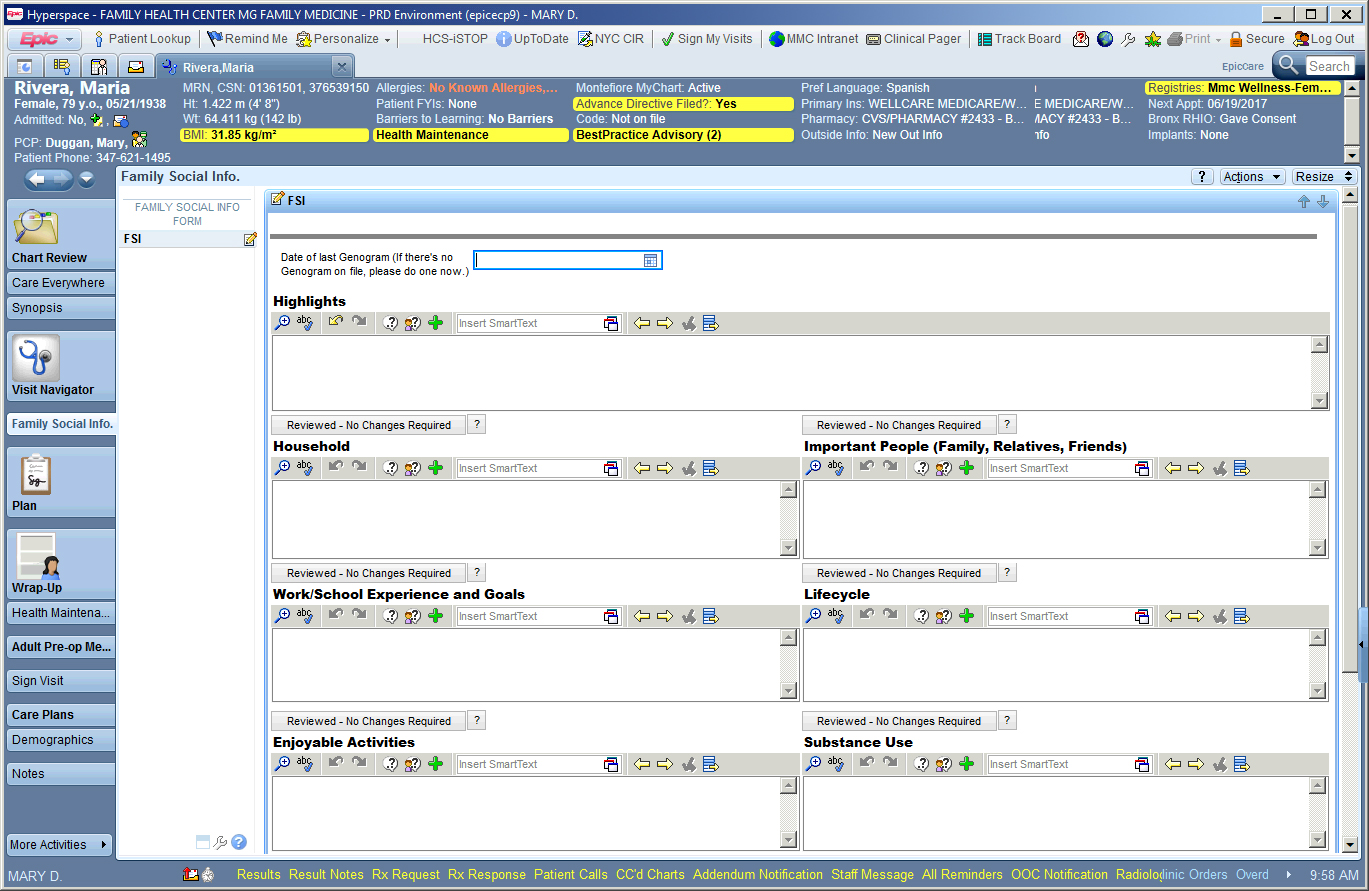

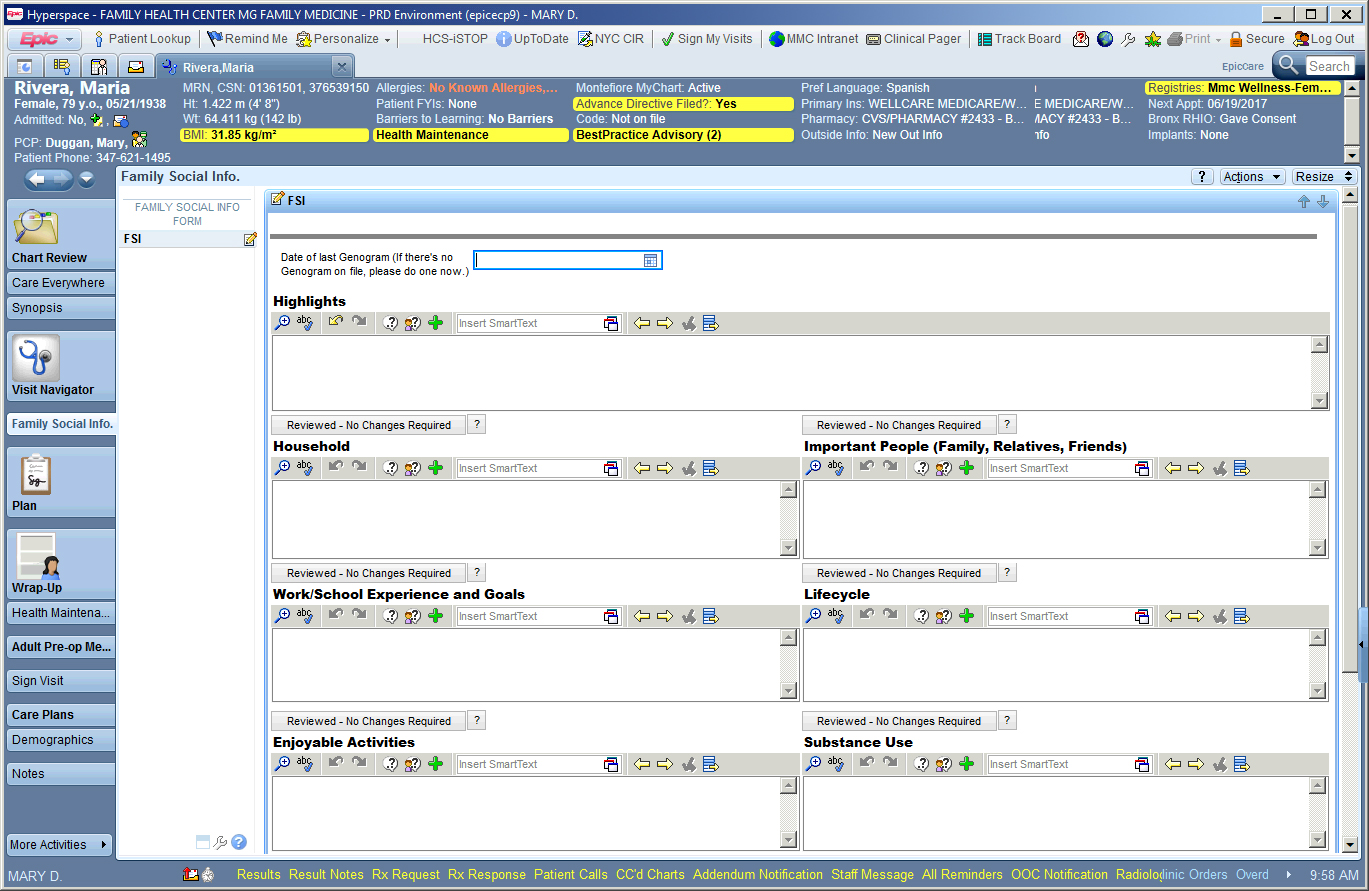

It may also be helpful to ask patients about their social risks in the context of broader conversations about their lives. Family medicine physicians at Bronx-based Montefiore Medical Center routinely ask patients about their goals, support network, activities they enjoy, and other assets that support their well-being.

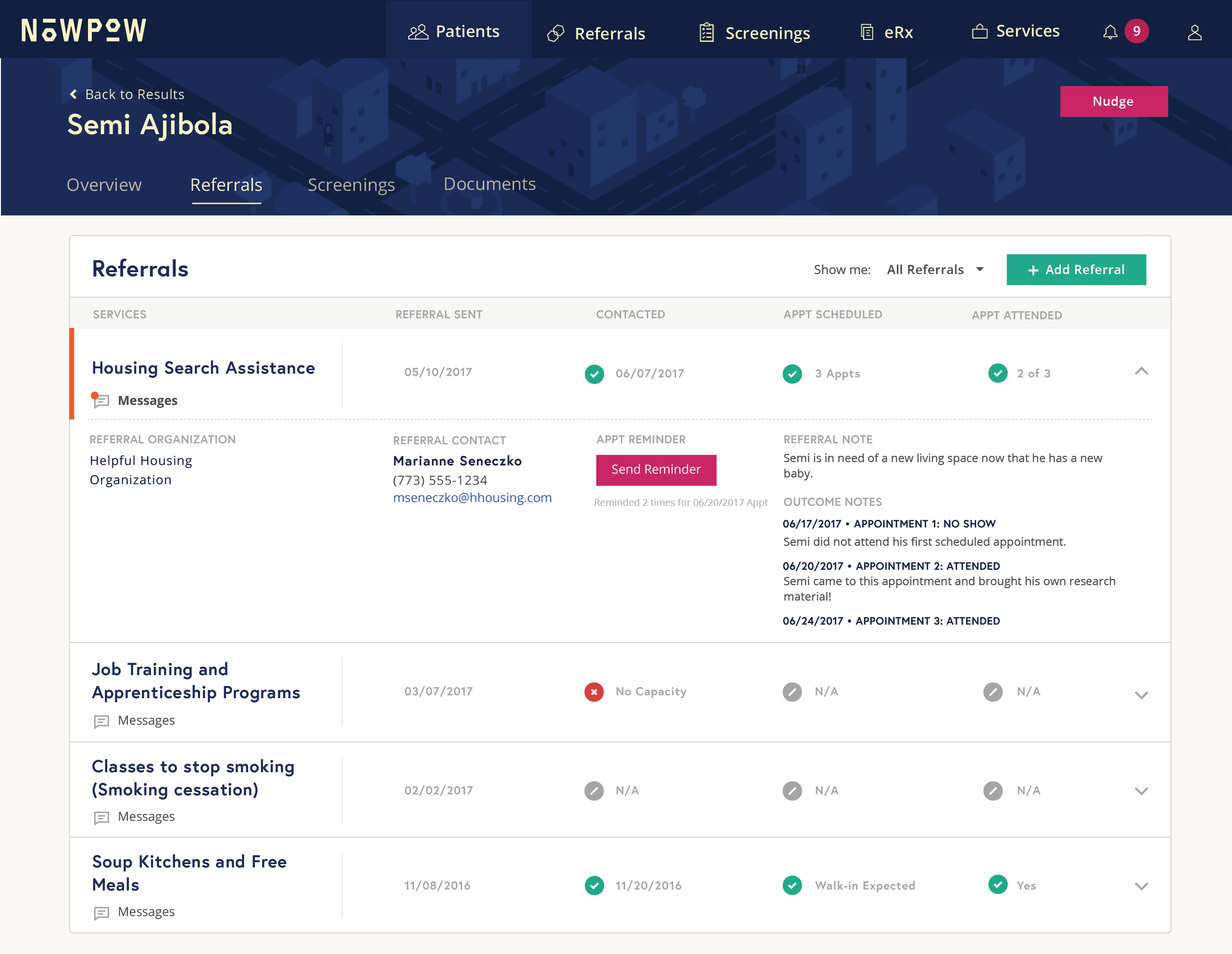

Screenshot of electronic medical record used by Montefiore Family Medicine Clinicians

Because of this complexity, health care leaders say it’s too soon to categorize patients by their social risks or weight their relative risk levels, as has been done for clinical conditions. “We’re very clear that social determinants of health matter,” says Alicia Atalla-Mei, Oregon Primary Care Association’s social determinants of health manager. “But we want to get a better picture of their impact and map out evidence-based interventions to address them before we develop and assign risk scores.”11

It’s also an open question whether it’s necessary to screen all patients for social risks or more efficient to tap other available sources of data to understand patients’ potential needs. For example, some providers are using geographic mapping to identify neighborhoods where there’s a high prevalence of deteriorated housing, gun violence, or other circumstances.12 “At Cincinnati Children’s we’re trying to map risk,” says Kahn. “Here’s a neighborhood with some of the highest readmission rates in the county, where 80 percent of people don’t own a car, and there’s no pharmacy within two miles. What happens when you discharge a patient there?” One goal of such work, Kahn says, would be to convince a pharmacy to partner with the hospital to address the problem of “pharmacy deserts.”

Vendors such as CentraForce Health have developed tools that leverage this kind of mapping data as well as other data sources outside of health care (e.g., consumer surveys describing shopping habits of individual patients and populations, their media usage, transportation, and other critical social factors such as education level and access to healthy food) that are being used by health systems to generate actionable insights about their patients’ lives and potential risks.

Making the Business Case

Documenting the impact of social needs interventions on health care use and costs may create the rationale for greater investment, whether from payers like Medicaid, which in places like Cincinnati have begun to invest in housing to promote better health, or from safety-net hospitals like Parkland that are channeling funds to community partners that help them reduce acute care use.

CareSource pays for its Life Services program through its foundation because Medicaid funds cannot be used to pay for workforce development, but that may be changing, according to VanZant.13 “We’re having conversations with legislators to say: If we want to pay for value, might there be an incentive for the number of people we transition off Medicaid to employer-sponsored insurance? Rather than focusing just on the sickest 10 percent of patients, might we shift a portion of funds to help the healthiest 50 percent gain independence?” she says.

With widespread awareness that health care is an important part of advancing health in America, “hospitals understand that is necessary to address patients’ social risk factors,” says Jay Bhatt, D.O., chief medical officer of the American Hospital Association’s Health Research and Educational Trust. “The challenge, of course, is what happens after a positive screen. Hospitals and other health care providers need to be able to connect patients with appropriate services, but frameworks and examples, resources, frontline clinician and leadership buy-in, and effective community partnerships all need to be in place to do so.”

Notes

1 Among other findings, one of five said they failed to fill prescriptions for lack of money; and one of six admitted they diluted infant formula to ensure limited supplies reached month’s end.

2 A. F. Beck, B. Huang, R. Chundur et al., “Housing Code Violation Density Associated with Emergency Department and Hospital Use by Children with Asthma,” Health Affairs, Nov. 2014 33(11):1993–2002.

3 See A. F. Beck, J. M. Simmons, H. S. Sauers et al., “Connecting At-Risk Inpatient Asthmatics to a Community-Based Program to Reduce Home Environmental Risks: Care System Redesign Using Quality Improvement Methods,” Hospital Pediatrics, Oct. 2013 3(4):326–34 and M. D. Klein, A. F. Beck, A. W. Henize et al., “Doctors and Lawyers Collaborating to HeLP Children—Outcomes from a Successful Partnership Between Professions,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 2013 24(3):1063–73.

4 See, for example, Leveraging the Social Determinants of Health: What Works?, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Foundation, June 2015, and Addressing Patients’ Social Needs: An Emerging Business Case for Provider Investment, Manatt Health Solutions, May 2014.

5 See, for example, L. Gottlieb, D. Hessler, D. Long et al., “A Randomized Trial on Screening for Social Determinants of Health: The iScreen Study,” Pediatrics, 2014 134(6):e1611-8.

6 City of Hope has integrated all supportive services under one department, including: pain and palliative care, psychology, psychiatry, social work, education, and navigation.

7 National Association of Community Health Centers, Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, Oregon Primary Care Association, Institute for Alternative Futures, Accelerating Strategies to Address the Social Determinants of Health: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (Bethesda, MD: NACHC; 2016). Available at http://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/toolkit/. Health centers already collect some relevant information as part of the Uniform Data System. Health centers already collect some relevant information as part of the Uniform Data System. The PRAPARE tool facilitates the process by providing a template that embeds questions in electronic health records; a companion toolkit outlines practical steps to address identified needs. The National Academy of Medicine has also created a standardized tool to screen patients for health-related social needs. See https://nam.edu/standardized-screening-for-health-related-social-needs-in-clinical-settings-the-accountable-health-communities-screening-tool/.

8 National Association of Community Health Centers, Association of Asian Pacific Community Health Organizations, Oregon Primary Care Association, Institute for Alternative Futures, Accelerating Strategies to Address the Social Determinants of Health: Protocol for Responding to and Assessing Patients’ Assets, Risks, and Experiences (Bethesda, MD: NACHC; 2016). Available at http://www.nachc.org/research-and-data/prapare/toolkit/. Sample size = 2,694 patients; r = 0.61.

9 V. R. Fuchs, “Social Determinants of Health: Caveats and Nuances,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Jan. 3, 2017 317(1):25–6.

10 For example, a recent study found that patients who screened positive for food insecurity did not always want help from their providers with that issue. See C. J. Bottino, E. T. Rhodes, C. Kreatsoulas et al., “Food Insecurity Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Can Offering Referrals Help Identify Families in Need?” Academic Pediatrics, http://www.academicpedsjnl.net/article/S1876-2859(16)30468-5/fulltext.

11 The National Quality Forum has developed recommendations on how to adjust for socioeconomic factors, as well as race and ethnicity, in performance measurement. See http://www.qualityforum.org/risk_adjustment_ses.aspx.

12 A. F. Beck, M. T. Sandel, P. H. Ryan, and R. S. Kahn, “Mapping Neighborhood Health Geomarkers to Clinical Care Decisions to Promote Equity in Child Health,” Health Affairs, June 2017 36(6):999–1005.

13 CareSource was able to negotiate from Ohio Medicaid a $500 per-member support fund, which cannot be paid directly to members but can be used to pay for services, e.g., training, that cannot be found for free in the community. CareSource says it has rarely had to use these funds because patients themselves have identified their own social supports.