BACKGROUND

Health system leaders worldwide are searching for innovative care delivery models that lower costs, improve quality, and increase access to services. India’s Narayana Health is one of the best-known examples of a health system that has achieved these goals.

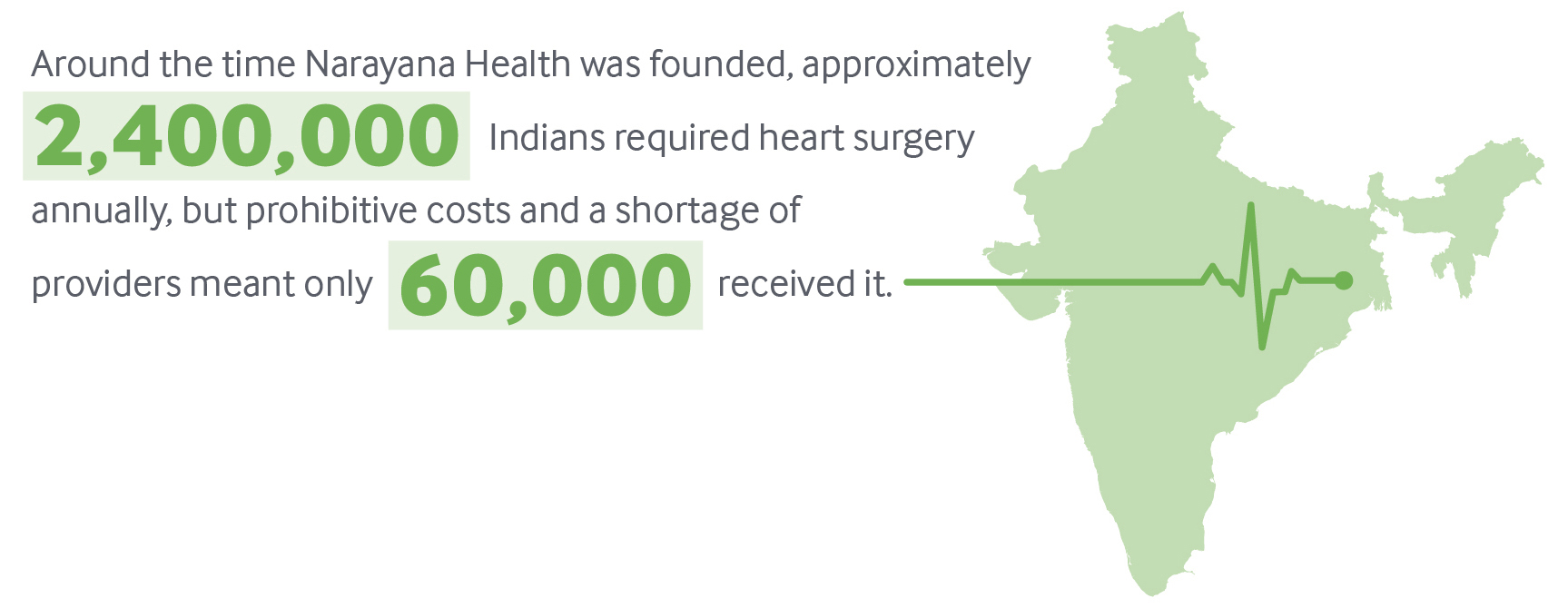

U.K.-trained cardiac surgeon Devi Prasad Shetty, M.D., who served as Mother Teresa’s personal physician after operating on her following her heart attack, founded Narayana Health in 2001 in Bangalore. Its mission: to provide high-quality, affordable cardiac care to everyone, regardless of ability to pay. Changes to Indians’ lifestyle and diet in recent decades have led to an unprecedented increase in heart disease.1 Around the time Narayana Health was founded, approximately 2.4 million Indians required heart surgery annually, but prohibitive costs and a shortage of providers meant only 60,000 received it.2

- India’s Narayana Health: A Model of Efficient, High-Tech Care

This gap inspired Shetty to create what is today one of India’s largest multispecialty hospital chains, comprising 31 tertiary hospitals across 19 cities. By combining innovative technology and a highly efficient delivery system, Narayana Health is able to optimize productivity and minimize costs. This has enabled it to both increase treatment capacity and expand the number of specialty services offered. In early 2016, the company’s share price rose more than 35 percent in its initial public offering.

This case study describes the Narayana Health model and the challenges the health system has faced in opening a new hospital in the Caribbean island of Grand Cayman. It also offers lessons for U.S. health care payers and providers on ways to dramatically reduce costs while maintaining high-quality tertiary care.

KEY PROGRAM FEATURES

- leveraging economies of scale

- using assembly line concepts for surgery

- reducing the average length of stay

- reengineering the design, materials, and use of medical equipment to reduce the cost of ownership.

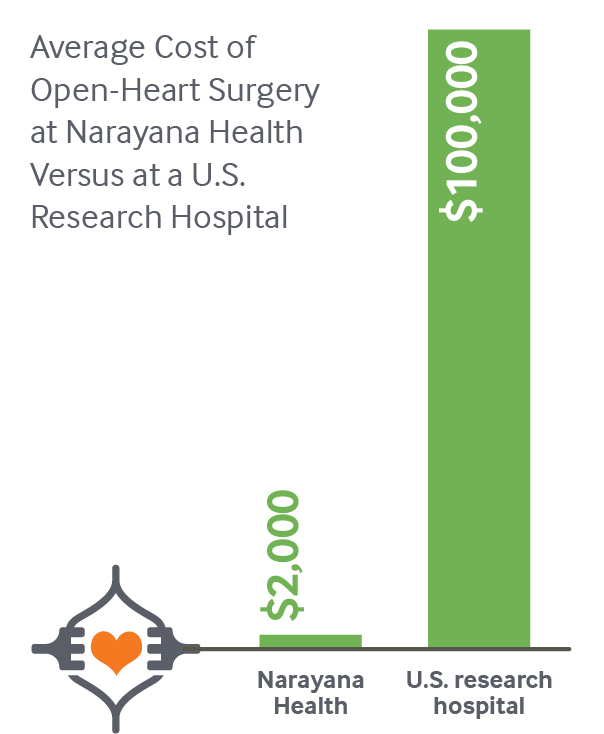

Because of these innovations, the average cost of open-heart surgery, as reported by Narayana Health, is less than $2,000. The same procedure at a U.S. research hospital typically costs more than $100,000.4

A Tight Focus on Efficiency

Narayana Health has achieved savings through smart use of equipment and telemedicine as well as efficient staffing procedures. The health system has built reliable and low-cost supply chains in India over the past decade and leverages economies of scale to further drive down prices. Utilizing a pay-per-use model with suppliers for some diagnostic equipment, it minimizes capital costs.5 Strict sterilization procedures, permitted by the Joint Commission International, enable reuse of some devices, such as guide wires and certain cardiology catheters that are typically disposed of after a single use. Centralized purchasing allows the system to take advantage of economies of scale. Bar coding of stock enables precise inventory counts at any time, minimizing storage costs and preventing unnecessary spending.

In addition to offering services at its own facilities, Narayana Health has one of the world’s largest telemedicine networks, connecting 800 centers globally. The system has treated more than 53,000 patients through telemedicine programs, increasing Narayana’s reach without requiring investment in physical infrastructure. Mobile outreach vans, meanwhile, increase access to diagnostic and consultation services in semiurban and rural areas of India.

A production-line approach to surgery, combined with task-shifting among staff, create an extremely efficient operating theater, resulting in many more procedures completed per day than is typical in the U.S. and elsewhere. Each surgeon performs 400 to 600 procedures annually, compared with 100 to 200 in the U.S.6 All staff members work at the top of their scope of practice: surgeons perform only the tasks they are uniquely qualified to do, while other clinicians perform tasks such as preoperative preparation, patient education, and charting. This enables many surgeries to be performed in a row, with surgeons completing one procedure and quickly beginning the next on a fully prepped patient. This high volume drives lower costs and better-quality outcomes, with surgeons quickly gaining experience and mastery.

Narayana Health’s well-known brand, social mission, and strong leadership — in addition to competitive compensation and incentive packages — attract and retain highly qualified cardiac surgeons and other tertiary care specialists. The system has approximately 16,000 employees, with 11,000 clinicians spread across the company, and 4,000 people are subcontracted for housekeeping and security.

Smart Use of Data to Reduce Costs, Monitor Performance

Use of information technology and data promote efficiency and standardization throughout Narayana Health. A centralized cloud environment connects all the hospitals, helping to streamline administrative tasks and enable performance monitoring.

The finance team generates profit-and-loss statements for executives every day, allowing them to identify and address capital flow issues as they arise. Financial data are reviewed monthly with unit heads and the CEO.

Key performance indicators for individuals and departments are monitored daily, and a real-time patient-complaint process provides a simple and powerful tool to identify and quickly correct performance issues.

Providing Affordable Care to All

Narayana Health hospitals serve anyone who needs care, regardless of their ability to pay. Each year, more than half of patients receive free or subsidized inpatient care, with an average discount of 15 percent. This is accomplished through philanthropy and a cross-subsidy model, in which higher-income patients pay more for nonclinical amenities, such as private recovery rooms. Since the total charges are still far below the cost of comparable services at other private hospitals, Narayana Health is still an attractive option for such consumers. The health system’s business model is sustainable because of its ability to attract so many patients who can pay full price.

SPREAD TO THE CARIBBEAN

In 2014, Health City Cayman Islands (HCCI), a 101-bed tertiary care hospital that follows the Narayana model, opened in the Caribbean island of Grand Cayman, which is part of the United Kingdom’s Cayman Islands territory. The venture is a partnership between Narayana Health and Ascension Health, the largest nonprofit and largest faith-based health system in the U.S. (See Appendix for details of HCCI’s business and staffing models.) Local factors have affected the implementation and success of the Narayana model in the Caribbean, in both positive and negative ways.

Facilitators of Success

The choice of Grand Cayman was driven by a convergence of factors, including the enthusiasm of local business leaders, the Caymanian government’s need to diversify its economy in the wake of the recent global recession, and Narayana Health’s desire to establish a presence in the region (see box). The island’s well-developed tourism industry, strong infrastructure, low crime rate, and geographic proximity to multiple new markets made it an attractive location.

Key Partners in Health City Cayman IslandsCaymanian businessmen Harry Chandi and Gene Thompson were critical in the genesis of HCCI. Chandi, a Cayman resident of Indian origin, became friends with Narayana Health founder Devi Prasad Shetty, M.D., after he treated Chandi’s father in India. Thompson was Chandi’s business partner and a third-generation Caymanian director of Thompson Development Ltd., a major development company. The Cayman government had approached Thompson about developing avenues for economic diversification. Chandi and Thompson, inspired by Shetty’s vision, were vital in brokering relationships between Narayana Health and the Cayman government and developing the project’s master plan. “Ignorance is empowerment,” said Thompson. “We knew no boundaries, limits, barriers; we only saw opportunities.” At the same time, Ascension Health, the largest faith-based and largest not-for-profit health system in the United States, was drawn to Narayana Health’s mission-driven approach. A subsidiary of Ascension, TriMedx, had been collaborating with Narayana to service equipment beyond its usual lifespan, resulting in reduced capital expenses and operating costs. The executive leadership team at Ascension saw the investment in HCCI as a way to provide affordable health care while affording the opportunity to test innovative quality- and cost-improvement strategies that could apply to the United States. |

The Caymanian government’s willingness to make sweeping changes to the regulatory and policy environments to accommodate HCCI was critical. The government changed nine laws and 13 regulations in two and one-half years, including its health practice law, which now recognizes Indian medical qualifications and approves Indian doctors and nurses to practice in the Caymans. Tort reform capped medical malpractice awards at $620,000, thereby reducing insurance costs for the hospital.7 Immigration law was changed to support expedited visa processing for people from countries that require a visa to enter Grand Cayman, and the duty tax was waived for imported medical supplies. The government also preapproved expansion to match the project’s 15-year master plan (see Appendix).

Efficient methods (e.g., building with insulated concrete forms that decrease air conditioning use by 40 percent) led to fast and affordable construction of the HCCI hospital, resulting in completion within budget in 12 months.

Challenges

In its early stage, several factors threatened to hinder the success of the model in Grand Cayman, including differences between the Narayana and local work culture, higher operational costs, and prevalent misconceptions about the hospital that discouraged local patients from seeking services.

HCCI imports most of its clinical staff from India, a practice that may be difficult to continue as it grows. Hospital leaders are working to embed the Narayana Health work culture, including continuous improvement, balancing multiple roles as needed, and task-shifting, among local clinicians. However, the model will also need to adapt to cultural norms in the Cayman Islands.

Higher operational costs and the supply chain logistics of an island also present challenges. Hospital leaders are looking for ways to reduce operational costs through approaches such as use of solar power, and are importing some supplies from India to find lower prices.

HCCI has also had to dispel myths that discouraged local patients from seeking care, including perceptions that low cost means low quality, that the hospital is a medical tourism institution that would not serve locals, that Indian doctors weren’t as good as Western doctors and might not speak English, and that the only services offered were through telemedicine. To help address these misconceptions, HCCI provided care to a few notable Caymanians, who then became advocates for the hospital.

Efficiency in ConstructionHCCI’s construction integrated many concepts from India, including Shetty’s philosophy of incorporating natural light into all areas of the building, especially operating rooms. There was a firm commitment to lean and green hospital design. For example, on-site oxygen manufacturing, use of solar power, and recycling water for nonpotable uses, mitigated environmental concerns, and should lead to long-term cost-savings “The sum total of multiple efficiencies in the construction process had greater impact than one silver bullet of saving,” says Thompson, a Caymanian businessman who helped develop HCCI. The hospital was built at $420,000 per bed, compared with an average of $1 million per bed in the United States. HCCI has just over 100,000 square feet, less than half the size of a typical Western hospital. This small footprint has also led to operational savings. |

Plan for Growth

In the short to medium term, HCCI is marketing its services to Caymanians and other Caribbean residents and Latin Americans covered by government or private insurance, as well as wealthy patients who pay out of pocket. Through a partnership with the Heart to Heart organization, HCCI also provides subsidized cardiac surgery for Haitian children. U.S. residents covered by traditional insurance are not the immediate target of patient growth, though self-insured companies may be willing to partner with HCCI.

To date, HCCI’s clinicians have focused on orthopedic surgery (32%) and cardiology procedures (26%), with 15 percent in cardiac surgery, 13 percent in general surgery, and 14 percent in other specialties. As the volume of patients increases, HCCI is expanding its specialties. New services include medical oncology, spine surgery, bariatric surgery, neurosurgery and neurology, plastic surgery, and urology. A sleep lab, sports medicine, surgical oncology, and a cancer institute with a radiation unit are expected.

The long-term plan also includes expansion to 2,000 hospital beds within 15 years, opening of a medical university, and a 1,500-unit assisted living facility that will serve people needing day-to-day medical supervision as well as healthy retirees wanting medical services nearby. Pharma-tourism — whereby people travel to purchase cheaper medicines — is also seen as a potential growth area.

RESULTS

Narayana Health

The Narayana Health model has been rigorously studied and its impacts on clinical quality and outcomes, access to care, and costs are well documented in the peer-reviewed literature. In 2007, the health system was responsible for 12 percent of all cardiac surgical procedures performed in India, with 25 procedures completed daily, six days per week.8 As noted above, its surgeons quickly develop expertise, resulting in patient outcomes that rival those in the United States. For example, Narayana Health reports a 1.4 percent mortality rate within 30 days of coronary artery bypass graft surgery, compared with 1.9 percent in the U.S.9 It also reports a 1 percent mortality rate for mitral valve replacement, and a door-to-balloon time of less than 90 minutes for 91 percent of cases; both rates exceed international benchmarks (Exhibit 1).10

Narayana Health’s operations in India are profitable. Eighty percent of its total revenue is generated from inpatient visits, 10 percent from outpatient visits, and 10 percent from remote consultations and diagnoses. To identify cost drivers and support efforts to further increase efficiency, the system is working with Stanford University researchers to develop a model to measure the time and cost of each part of the patient encounter, from walking in the door through follow-up. Colleagues at Duke University are working with HCCI to develop a similar model, which will allow managers to target specific ways to drive efficiencies.

Health City Cayman Islands

Although it is too early to analyze HCCI’s treatment outcomes, the hospital’s cost advantage is evident. HCCI’s bundled pricing structure is typically set at 30 percent to 50 percent of U.S. fees for the same procedures. For example, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery typically costs $100,000 or more in the United States, while HCCI charges around $25,000. HCCI is focused on expanding services and reducing costs further, with the ultimate goal of providing CABG surgery for $15,000 and joint replacement surgery for $10,000.

HCCI appears to be well positioned to change the status quo related to the costs and processes of surgery for the Americas and the Caribbean. However, sustainability will depend on the company’s ability to increase patient volume in all clinical areas.

POTENTIAL FOR SPREAD IN THE UNITED STATES

Narayana Health is a proven model of what’s known as “frugal innovation,” providing high-quality outcomes for lower cost and thereby expanding access to critical services. It shows that the combination of several different, focused innovations can lead to dramatic results, without necessarily having to disrupt existing systems. While it is unlikely that the model could be replicated wholesale in the U.S., because of the regulatory changes that would be required, it offers lessons on how to significantly reduce costs.

One aspect of the Narayana Health model that is particularly relevant for the U.S. — which spends more on health care than other high-income countries but has worse outcomes — is its focus on finding efficiencies in every aspect of operations and putting the savings to work to increase access and affordability for patients.11 At Narayana Health hospitals, each receptionist, billing specialist, nurse, lab technician, and physician knows the costs of every material they use and every procedure they recommend. Similar tools to identify cost drivers could be adopted in the U.S., building on existing efforts to promote price transparency. Having more data on the costs of care and out-of-pocket costs to patients could motivate U.S. health care providers to increase efficiency, particularly if reducing costs meant that more people could receive high-quality, affordable care.

There is also opportunity in the U.S. to rely on advanced practice providers, including physician assistants and nurse practitioners, to provide many more aspects of medical and surgical care. Such task-shifting, combined with a “focused factory” approach to patient throughput, could clear bottlenecks in surgery and lead to higher volumes, better outcomes, and cost reductions.12 Some U.S. providers are following similar approaches, including CareMore, which manages a Medicare Advantage plan that uses nurse practitioners and other team members to offer chronic disease management services and deploys physicians to care for sicker patients. Iora Health employs lay health coaches to encourage behavioral changes in patients, freeing up time for clinicians to concentrate on diagnosis and treatment.13

Targeting Multiple MarketsIn the Cayman Islands, employers are required by law to offer health insurance coverage to their employees. Those who do not have employer-sponsored coverage are covered by government plans, resulting in nearly universal insurance coverage and very low out-of-pocket expenditures for patients. HCCI reports that for its Caymanian patients, 95 percent of health spending is through insurance, an anomaly in the Caribbean. HCCI has contracted with insurance providers in the Cayman Islands and is working to attract local residents, including higher-income patients who typically have gone abroad for specialty care because local services have been scarce or unavailable. However, Cayman Island’s population of just 55,000 is not sufficient to drive the efficiencies that are the hallmark of the Narayana Health model. Therefore, the HCCI marketing team is analyzing health care service gaps in the Caribbean market. It is working with insurance companies, self-insured companies (which have greater incentives than do traditional insurers to cut costs), and cruise lines. The main targets for near-term growth are Jamaica, Turks and Caicos, the Bahamas, Trinidad, St. Maarten, and the Dominican Republic. In April 2015, HCCI earned accreditation by the Joint Commission International, making it one of the youngest hospitals to receive the international certification. This has given the hospital significant credibility and should strengthen its ability to attract customers from regional and international markets. HCCI’s medium-term strategy will be to target patients from the United States and Canada, with longer-term prospects from South America and Europe. In Canada, for example, marketing strategies target people for whom the opportunity cost of waiting for surgery outweighs the price of paying out of pocket at HCCI. |

Emerging provider payment mechanisms also may serve as incentives for U.S. health systems to adopt many of the frugal innovations developed by Narayana Health. The spread of bundled payments for episodes of care, as well as accountable care contracts that hold providers financially responsible for the quality and total costs of designated patient groups, shift greater financial risk to providers — thus creating greater urgency to reduce costs while maintaining quality. Large self-insured employers are also driving utilization of high-volume centers of excellence for high-acuity services, such as the collaboration between Lowe’s and the Cleveland Clinic.14 Continued growth in such arrangements could promote the Narayana Health model of high-volume specialization. Finally, the increasing availability of health care price and outcomes data may create incentives for employers to look for more efficient health care providers.

By bringing high-quality, low-cost specialty care within a few hours of travel time from the U.S., HCCI has created an alternative to U.S.-based care that could, over time, force health systems to reduce prices or risk losing market share. Surgical treatment of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and orthopedic conditions (including joint replacements) are top drivers of U.S. health care expenditures, and demand for these services will increase with the aging population.

Unlike other medical tourism destinations such as Thailand and India that require significant travel or out-of-pocket payments from international patients, the HCCI model can be implemented in conjunction with U.S. insurance companies, which are increasingly covering medical tourism. BlueCross’ Companion Global Healthcare program, supported by BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina and BlueChoice HealthPlan of South Carolina, is one such framework already in place.15 Insurers and large employers could cover the entire cost of travel for the patient and a companion to Grand Cayman, surgery at HCCI, and postoperative care at home and still potentially save half the average costs of the procedure in the United States.

While full-scale replication of the Narayana Health model in the U.S. is unlikely, U.S. health care providers can learn and apply lessons from this efficient and results-driven provider.

APPENDIX. HEALTH CITY CAYMAN ISLANDSBusiness ModelNarayana Health’s mission to serve all patients, regardless of their ability to pay, is sustained through the health system’s efforts to drive down operational costs, promote high patient volume, and attract a substantial proportion of full-pay patients by offering high-quality care and lower costs than the competition. The Health City Cayman Islands venture seeks to replicate this success, while adjusting its approach to meet the needs of a different population, payer mix, and operating environment. The cost of building and launching the HCCI hospital was $70 million. Compared with India, the cost of utilities, personnel, and supplies are far higher in Grand Cayman, and many of these costs will remain higher. To help reduce utility costs, HCCI recycles water for reuse and is planning a solar farm. Some operating costs will be reduced over time by economies of scale and development of more efficient supply chains. For example, to capitalize on Narayana Health’s low-cost supply chains, HCCI procures most supplies directly from India. Even though the added time and unpredictable nature of sea transport complicate inventory management, supplies imported from India still cost a fraction of what they would cost in other markets. Medicines are procured from FDA-approved companies in India when possible, and the remainder come from the United States or the United Kingdom. As patient volumes increase, HCCI expects to shift from on-demand orders to bulk orders, lowering costs. True to the Narayana model, HCCI doctors are involved in the acquisition process to ensure they consider costs and avoid unnecessary expenses. The Narayana Health business model is designed for India, where a majority of health expenditures are out of pocket (58% of total health expenditures) and most patients finance their own care.a To serve the Cayman Islands and Latin American markets, where the majority of people are insured, HCCI must adjust its pricing, billing, and marketing strategies to the preferences of insurers. Whereas Narayana Health pricing is transparent, HCCI does not publish prices because it needs to allow for negotiation with insurance companies. HCCI uses bundled, fixed pricing, rather than billing by codes, and typically sets prices at one-third to one-half of average U.S. prices. Eschewing billing codes in favor of bundled pricing for procedures results in significant efficiencies for HCCI (it employs only two billing staff for the entire hospital) and caps risk for insurance companies. The bundled prices include consultations, preoperative and postoperative investigations, admission charges, surgical fees, operating room fees, anesthesia, implant costs, room and food charges, medications and surgical consumables, transportation, and all physician visits up to two weeks after surgery. While bundled pricing would seem to be attractive to U.S. insurers, HCCI has learned that most private U.S. insurance companies still want to receive itemized bills to match U.S. billing codes, though many are piloting bundled payment models. Narayana Health leaders report that about 70 percent of the patients at its Cardiac Hospital pay in cash at the time of service. However, HCCI faces 45-to-50-day waits to receive payment from insurance companies, making cash-flow management more difficult. Staffing ModelLike Narayana Health, HCCI utilizes lean management principles. For example, staffing is planned according to the minimum requirements based on patient volume. HCCI staff also typically wear multiple hats as appropriate for their competencies, skills, and training (e.g., the head of internal medicine also heads the pharmacy). This is partly a function of current patient volume, but also reflects a cultural ethos HCCI sought to replicate by bringing teams from India, most of whom were trained at Narayana. Having the ability to balance multiple tasks is a key criterion in selecting candidates for HCCI. Internal hiring is also prioritized to maintain the strong organizational culture. To date, there are 268 employees at HCCI, with about two-thirds recruited from India. The majority of clinical staff were recruited from Narayana Health in India, in part because there are not enough medical specialists locally. Importing clinicians from Narayana also promotes fidelity to its work culture. HCCI has committed to the Caymanian government to maintain a minimum of 25 percent to 30 percent local employees (currently at 30%). To meet this goal over the long term, HCCI launched a student intern program (with 300 interns expected) and is working with the government to strengthen the school science curricula and increase students’ exposure to the health care professions. In 15 years, HCCI plans for one-third of its staff across all categories, including clinical, to be Caymanian. Policy and Regulatory Changes Made to Enable HCCI’s ModelThe Caymanian government worked with Narayana Health and Ascension to change laws and regulations to enable the adaptation of the Narayana model to the Caymans. Changes were made to the following laws, which were implemented through changes to 13 regulations.

a World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure Database. |