When Maureen was faced with the loss of her income, she found herself unable to pay rent and was evicted from her apartment. She moved into her car with her dog, Trenor, on the streets of Ventura, California. Living with diabetes made it difficult to manage her health and she landed in the hospital. Her situation was complicated by memory loss and the risk of COVID-19. Maureen’s condition stabilized after several days and hospital staff recommended that she receive ongoing care. She needed somewhere to recuperate until she could find a permanent place to live.

To meet Maureen’s needs, the hospital connected her to National Health Foundation (NHF), which offers recuperative care in Los Angeles and Ventura counties. She stayed for close to a month in a home-like facility that provided her with social support and intensive care management, paid for by the hospital. At the end of her stay, she transitioned to a sober living facility and was happily reunited with Trenor.

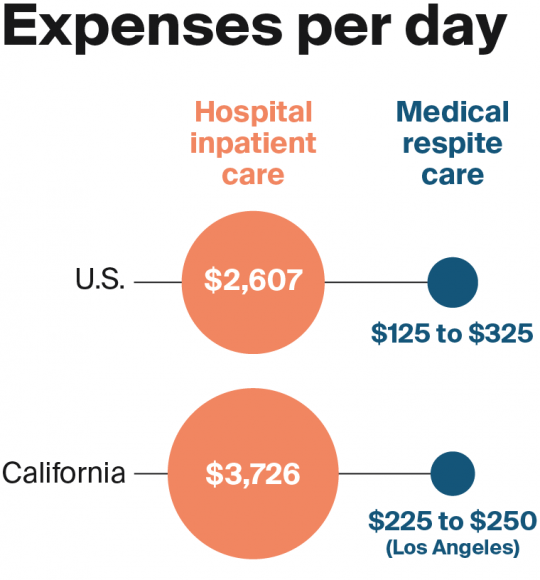

Unfortunately, stories like Maureen’s remain the exception because many areas lack an appropriate place for homeless patients to recuperate after a hospitalization. People experiencing homelessness often live with chronic illnesses that may be complicated by mental health or substance use disorders as well as unmet social needs, yet many receive inadequate health care.1,2 Consequently, many have repeated and prolonged hospital stays,3 make frequent emergency department (ED) visits,4 incur high health care costs,5 and experience poor health outcomes.6

To address this gap in transitional care for homeless patients, community stakeholders across the country have developed more than 100 posthospital medical respite programs since the 1980s, with more under development.7 In addition to promoting improved recovery and reduced costs of care, medical respite programs can play an important role in a continuum of services to prevent homelessness,8 which has taken increased urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic. This case study — the latest in a series describing models of care for high-need, high-cost patients — describes how NHF has developed a sustainable business model and attracted strong community support to help end the homelessness crisis in southern California.9