Abstract

- Issue: Medical debt negatively affects many Americans, especially people of color, women, and low-income families. Federal and state governments have set some standards to protect patients from medical debt.

- Goal: To evaluate the current landscape of medical debt protections at the federal and state levels and identify where they fall short.

- Methods: Analysis of federal and state laws, as well as discussions with state experts in medical debt law and policy. We focus on laws and regulations governing hospitals and debt collectors.

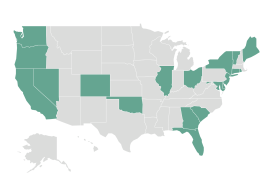

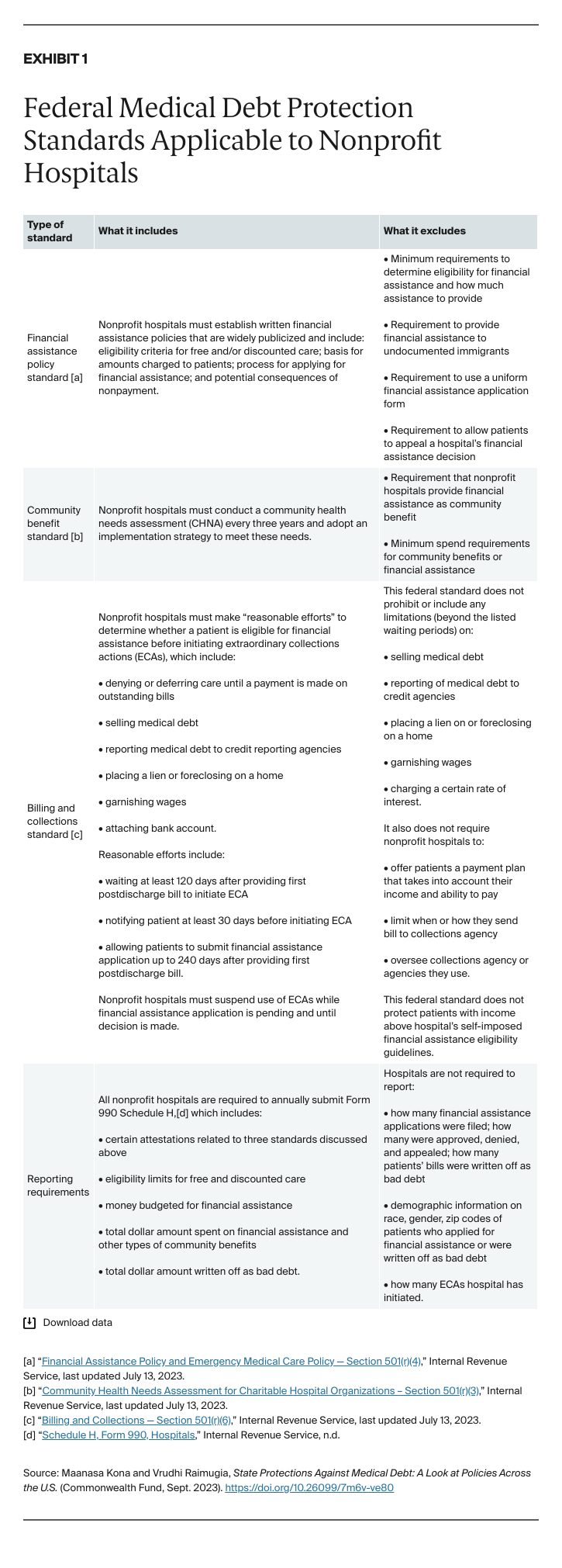

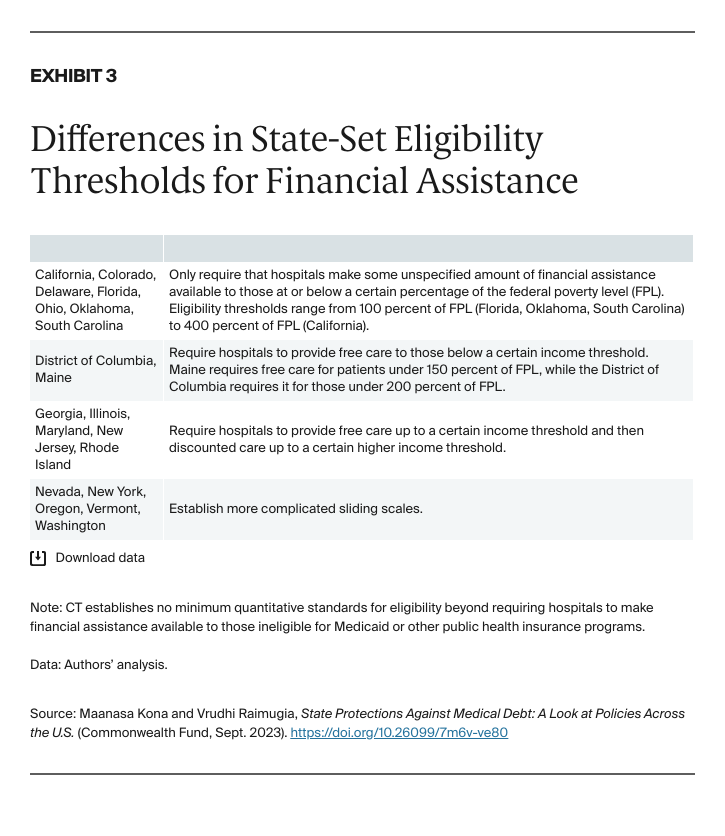

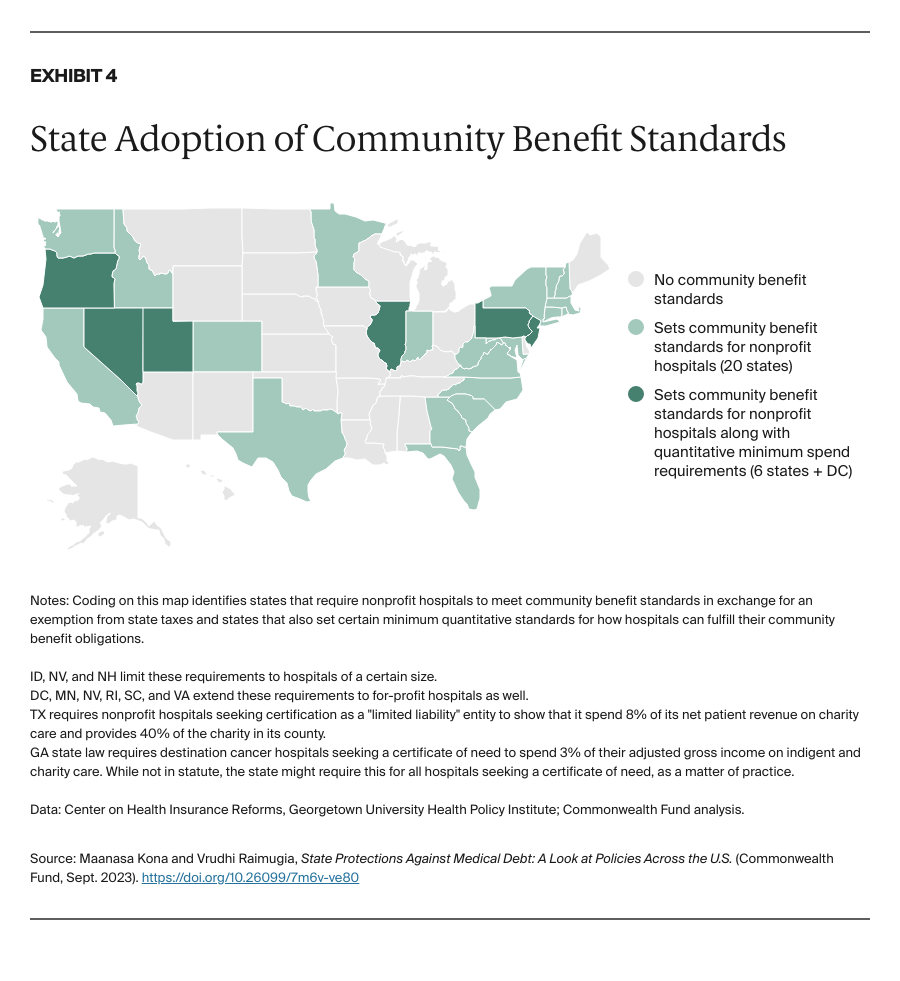

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Federal medical debt protection standards are vague and rarely enforced. Patient protections at the state level help address key gaps in federal protections. Twenty states have their own financial assistance standards, and 27 have community benefit standards. However, the strength of these standards varies widely. Relatively few states regulate billing and collections practices or limit the legal remedies available to creditors. Only five states have reporting requirements that are robust enough to identify noncompliance with state law and trends of discriminatory practices. Future patient protections could improve access to financial assistance, ensure that nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax exemption, and limit aggressive billing and collections practices.

Introduction

Medical debt, or personal debt incurred from unpaid medical bills, is a leading cause of bankruptcy in the United States.1 As many as 40 percent of U.S. adults, or about 100 million people, are currently in debt because of medical or dental bills.2 This debt can take many forms, including:

- past-due payments directly owed to a health care provider

- ongoing payment plans

- money owed to a bank or collections agency that has been assigned or sold the medical debt

- credit card debt from medical bills

- money borrowed from family or friends to pay for medical bills.

This report discusses findings from our review of federal and state laws that regulate hospitals and debt collectors to protect patients from medical debt and its negative consequences. First, we briefly discuss the impact and causes of medical debt. Then, we present federal medical debt protections and discuss gaps in standards as well as enforcement. Then, we provide an overview of what states are doing to:

- strengthen requirements for financial assistance and community benefits

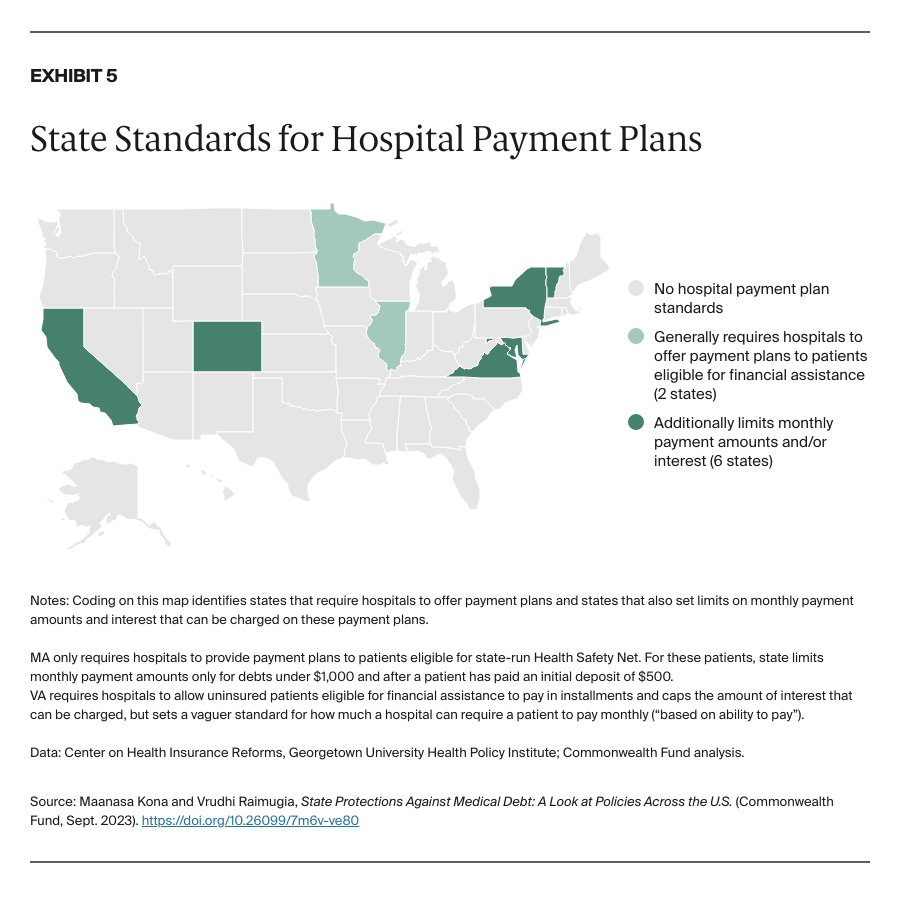

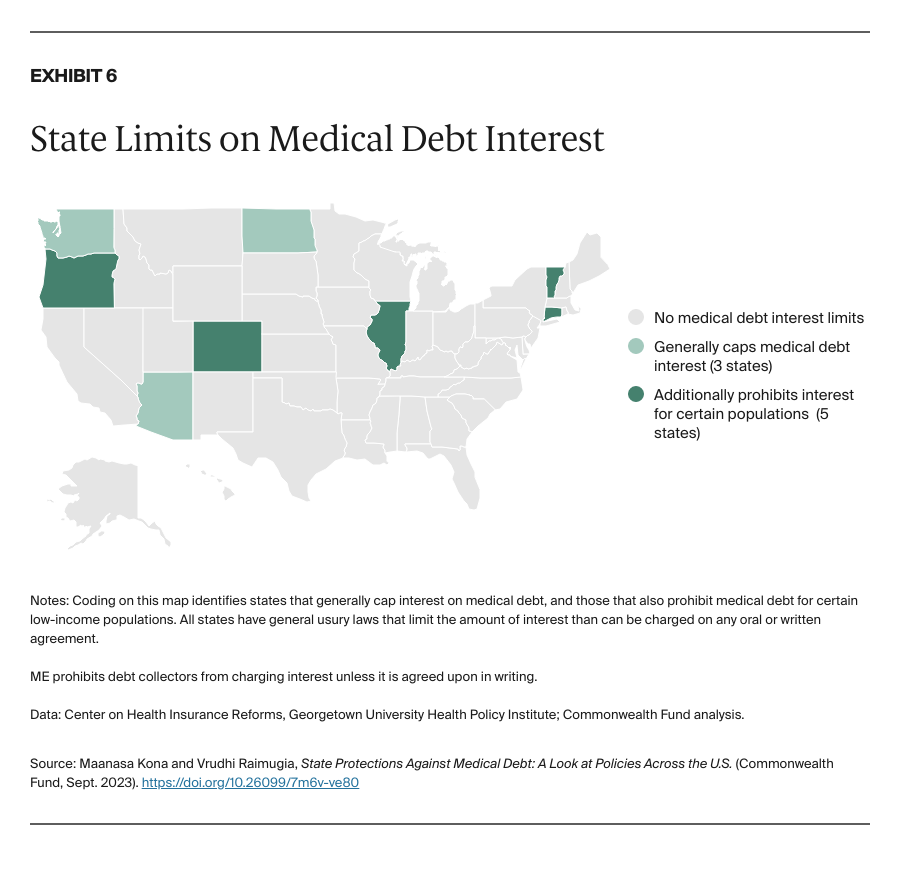

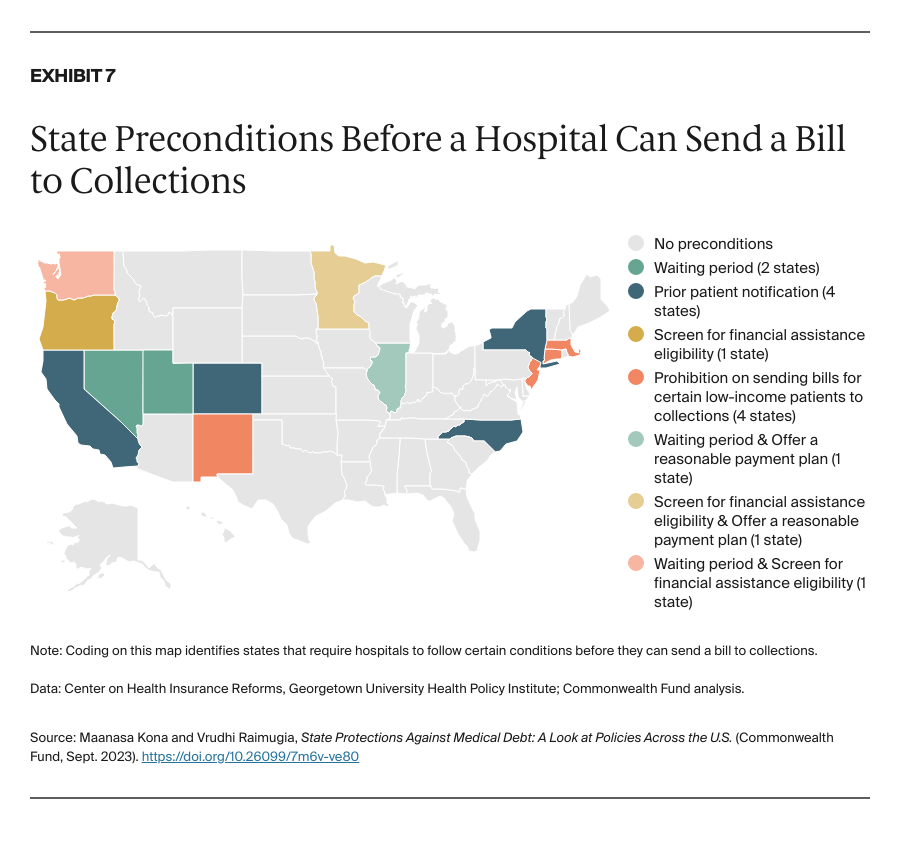

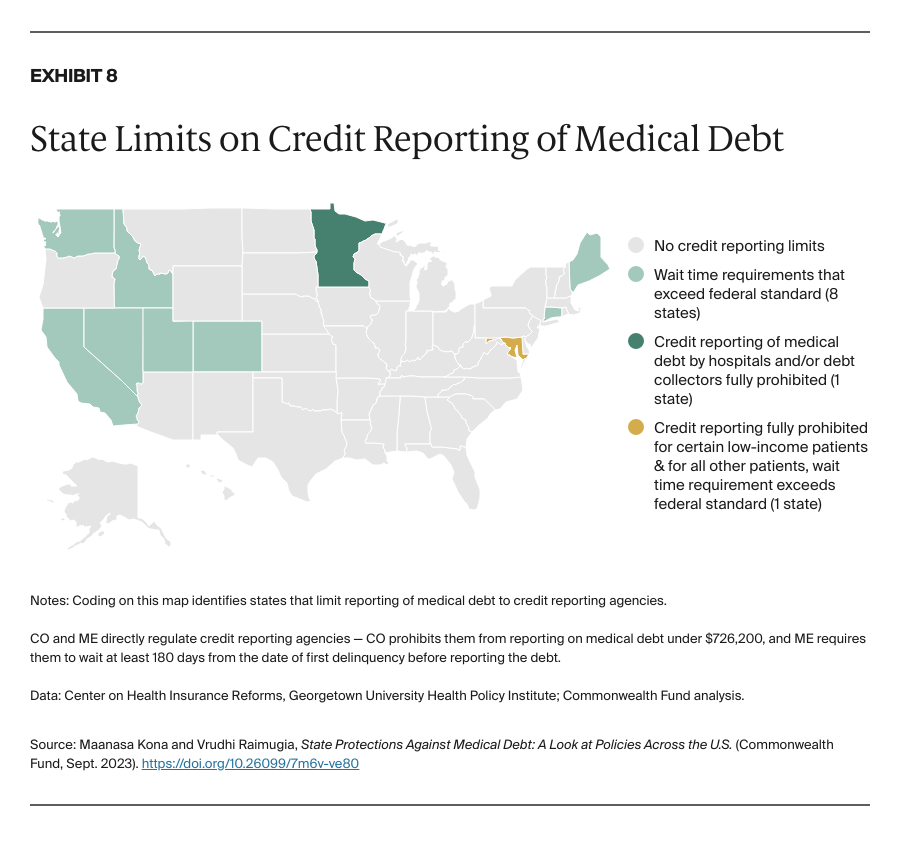

- regulate hospitals’ and debt collectors’ billing and collections activities

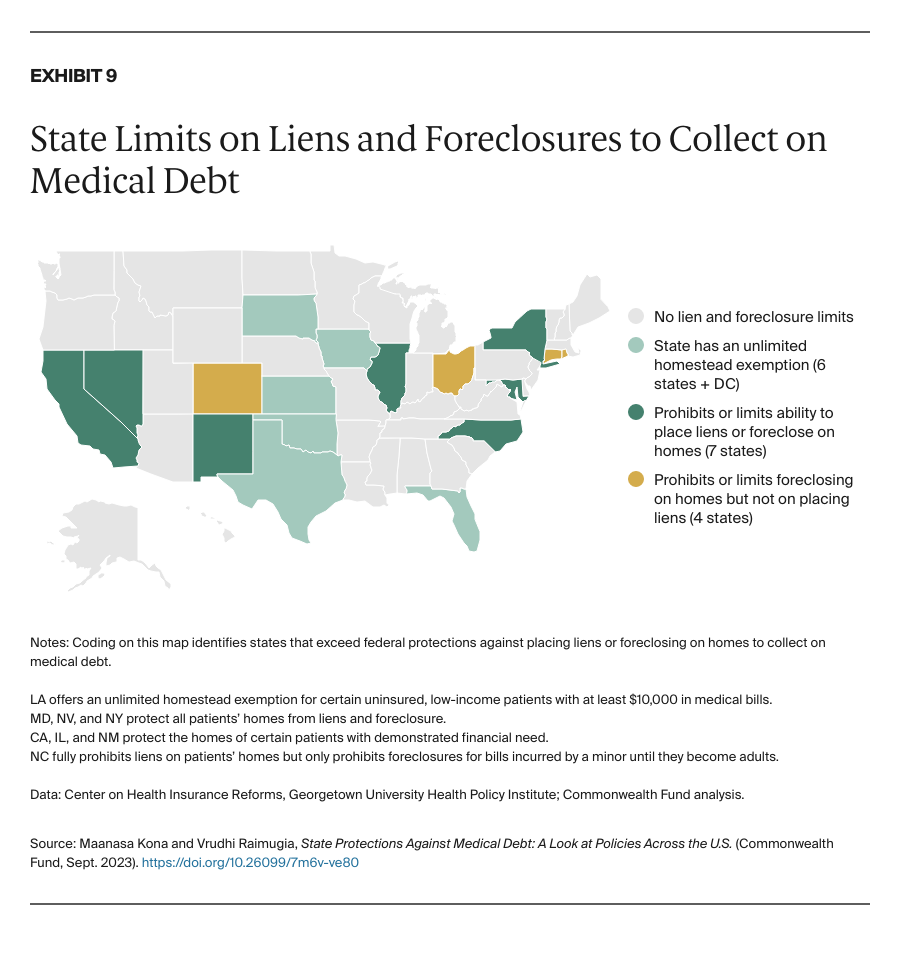

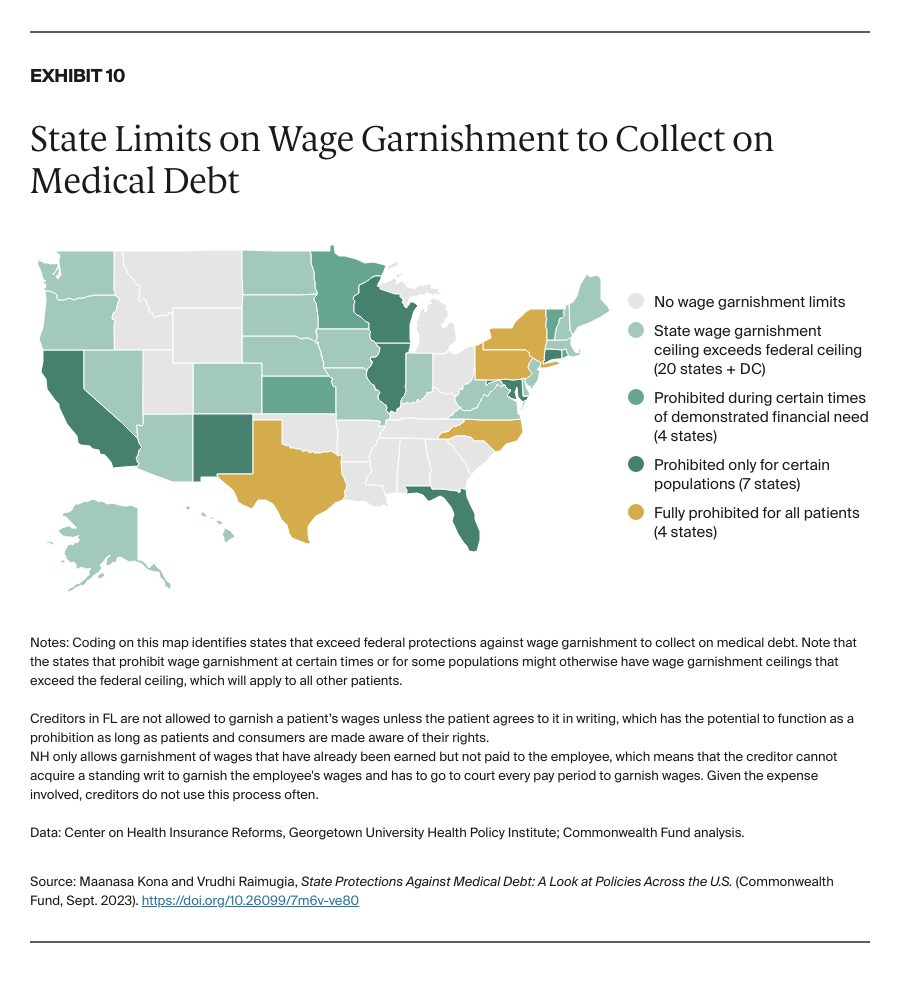

- limit home liens, foreclosures, and wage garnishment

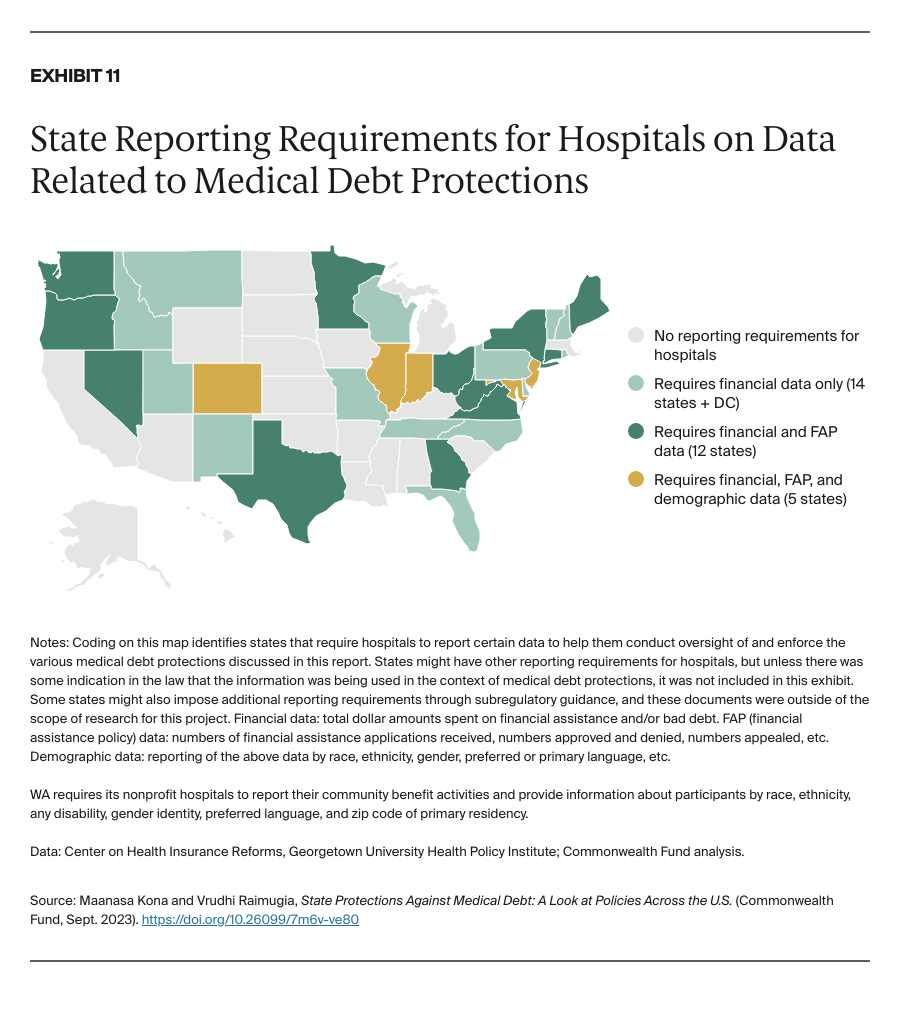

- develop reporting systems to ensure all hospitals are adhering to standards and not disproportionately targeting people of color and low-income communities.

(See the appendix for an overview of medical debt protections in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.)