Abstract

- Issue: To encourage greater use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, states took action to enhance private insurance coverage of telemedicine. As temporary orders and voluntary insurer efforts end, policymakers are considering how best to regulate telemedicine post-pandemic.

- Goal: To better understand the changing regulatory approach to telemedicine in response to COVID-19.

- Methods: A review of state actions to expand individual and group health insurance coverage of telemedicine between March 2020 and March 15, 2021, and a scan of statutes existing prior to March 2020 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Structured interviews with insurance regulators in 10 states that increased access to telemedicine during the pandemic.

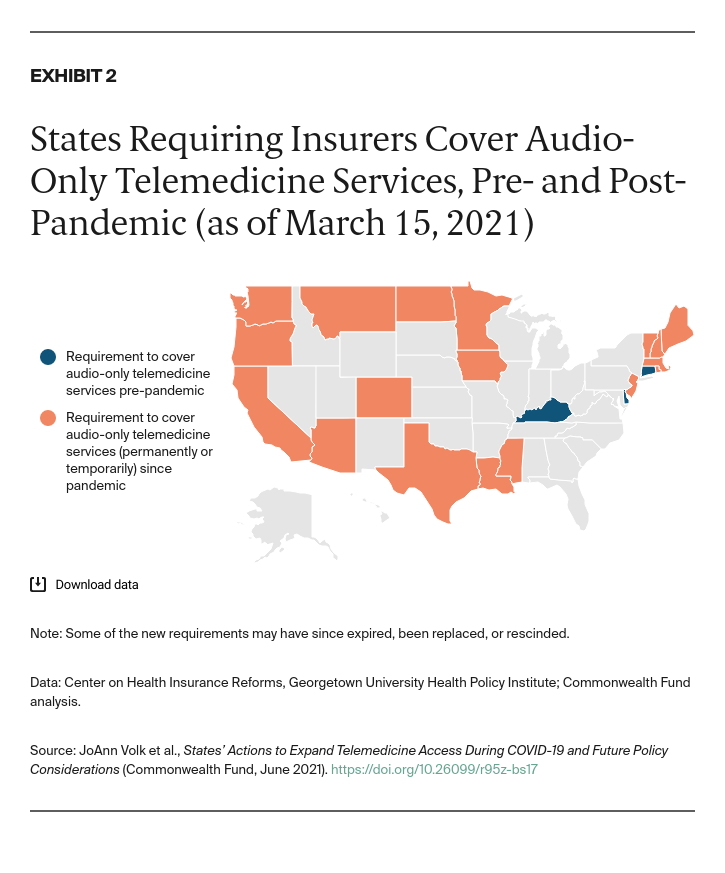

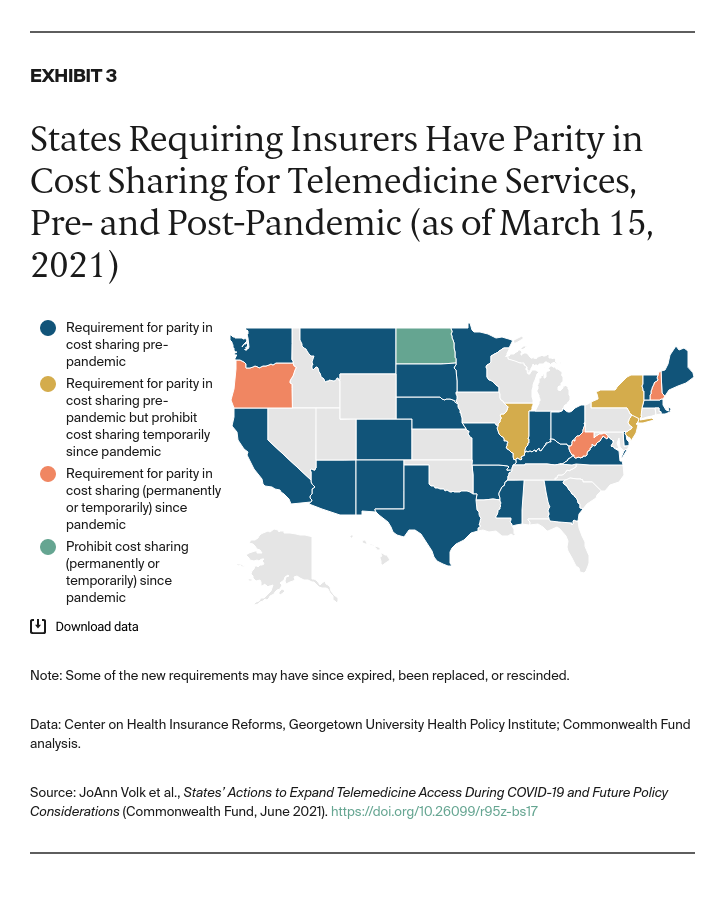

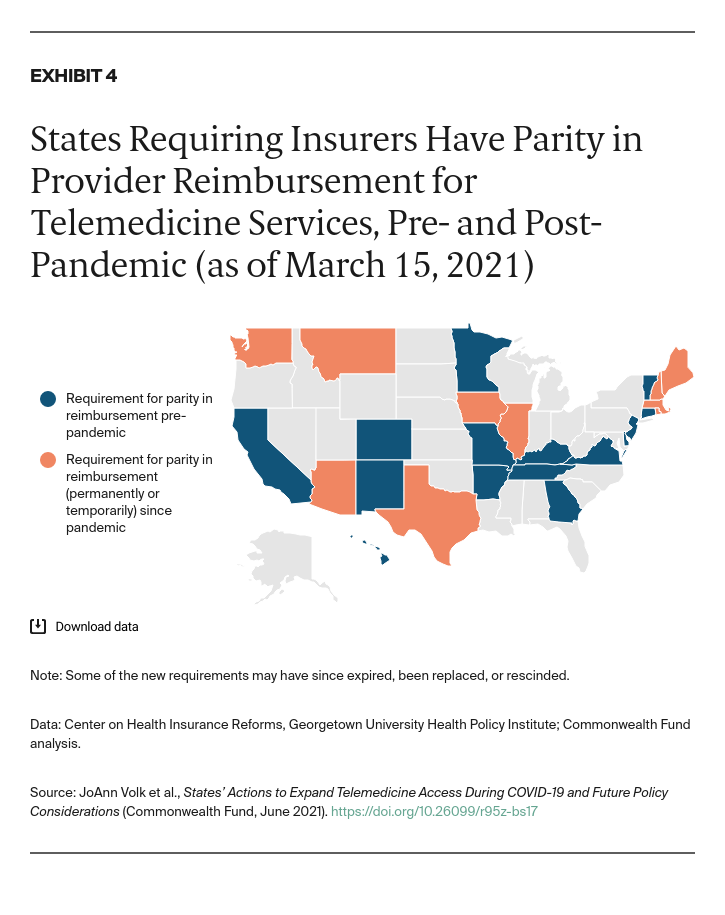

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Twenty-two states changed laws or policies during the pandemic to require more robust insurance coverage of telemedicine. States focused on three key areas: requiring coverage of audio-only services, waiving cost sharing or requiring cost sharing no higher than identical in-person services, and requiring reimbursement parity between telemedicine and in-person services. Data on how longer-term expansion of telemedicine affects access, cost, and quality of care may help shape future policies.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent need for remote access to health care to reduce the risk of community spread and protect patients. Although telemedicine has long been used to deliver health care services, take-up has historically been limited.1 A 2018 survey of physicians found just 18 percent had used telemedicine to deliver care, and less than 10 percent of U.S. residents had experience with telemedicine.2 By one estimate, less than 1 percent of medical services and treatments were provided through telemedicine in January 2020.3

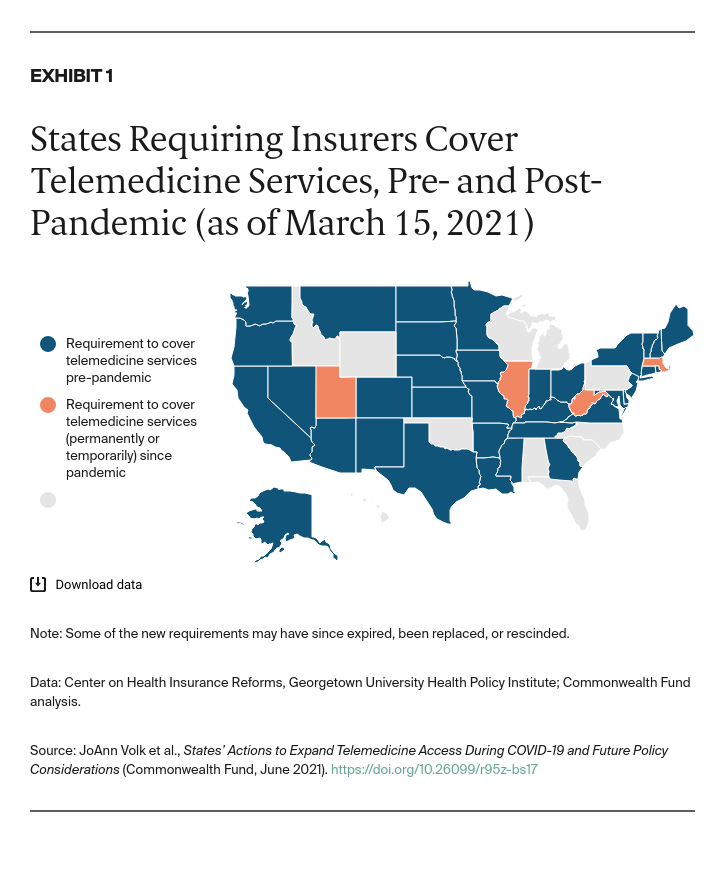

Before the pandemic, most states (36) required state-regulated individual and group health insurance to cover telemedicine visits. Half of states (25) required insurers to limit cost sharing, while just 15 required insurers to reimburse providers for a telemedicine visit on par with the reimbursement for an in-person visit. Only three states required coverage of audio-only telemedicine visits (Appendix A).

To encourage greater use of telemedicine among providers and patients during the pandemic, federal regulators temporarily relaxed restrictions for Medicare-paid visits in March 2020.4 Guidance raised Medicare payment for telemedicine visits to the same level as in-person visits, waived or reduced cost sharing for patients, and allowed audio-only visits, among other changes.5 Federal officials also encouraged states and insurers to provide similar flexibility under private insurance (such as by waiving certain federal privacy and security standards).6

States did just that, and some insurers voluntarily took steps to encourage greater use of telemedicine.7 Since these changes, telemedicine use has greatly expanded from a tiny proportion of office visits pre-pandemic to a high of 16 percent of visits at large practices (more than 100 clinicians) by mid-April 2020.8 Evidence suggests virtual visits for behavioral health increased substantially, in part to accommodate greater demand for such services during the crisis.9

We reviewed state actions — including new statutes, emergency orders, and subregulatory guidance — related to state-regulated individual and group health insurance coverage of telemedicine from the start of the pandemic in March 2020 to March 15, 2021. We also conducted a scan of statutes existing prior to March 2020 in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. In addition, we interviewed insurance regulators in 10 states that increased access to telemedicine during the pandemic.10

Findings

States Moved Quickly to Enhance Telemedicine Coverage

Twenty-two states changed laws or policies during the pandemic to require more robust insurance coverage of telemedicine. They used legislation, executive orders, and other agency actions, such as bulletins, notices, and executive orders from the department of insurance or a similar agency (Appendix B).

Most of these states pursued changes via administrative action. Use of executive authority allowed states to move relatively quickly during the crisis, though it has meant that the new telemedicine coverage requirements are temporary. For example, seven governors included specific telemedicine coverage requirements in executive orders, which are binding during the public health emergency but expire thereafter.

Some states used bulletins, notices, or executive orders from the department of insurance or a similar agency to enhance coverage. Administrative action also moved through various other vehicles (such as bulletins, notices, and executive orders from the department of insurance or similar agency) in states where sufficient statutory authority already existed or where an executive order created new authority without detailing specific requirements.

Eight states passed new legislation. Although the legislative process takes more time, it is necessary for permanent changes.11

States Chose Key Policy Changes to Expand Telemedicine Coverage

Four states that did not previously require coverage of telemedicine services changed their policies during the pandemic, bringing the total number of states that currently require coverage to 40 (Exhibit 1). In addition to securing this broad coverage obligation, states took other steps to enhance coverage and ensure access to health services while in-person care was limited during the pandemic. Telemedicine provides such access when medically appropriate.