Considering Future Policy Actions

With more than 200 COVID-19-related regulatory changes still in effect on a temporary basis, it is likely that the Biden administration and Congress will continue efforts to modify and extend at least some additional changes.

Because it normally takes at least six months to propose, finalize, and implement new Medicare rules, CMS and Congress may now begin to consider which additional provisions should be made permanent. They also may choose to modify these policy actions or add companion policies to mitigate unintended consequences for beneficiaries or Medicare program spending. Given that the effects of all COVID-19-related regulatory changes are not yet clear, CMS could explore these impacts and provide findings to policymakers and other stakeholders in a transparent manner.

With more than 200 COVID-19-related regulatory changes still in effect on a temporary basis, it is likely that the Biden administration and Congress will continue efforts to modify and extend at least some additional changes.

Research on Effects of Changes Needed

As previously mentioned, policymakers and health care stakeholders still know too little about the actual effects of these policy changes. Yet some of these changes are likely having a significant impact on how care is provided to Medicare beneficiaries.

Many of the changes, such as waiving the three-day hospital stay requirement for skilled nursing facility (SNF) services and expanding the use of telehealth, are already being studied on a smaller scale, through CMS Innovation Center demonstrations and Medicare Advantage (MA) plans’ use of certain Medicare requirement waivers and supplemental benefits.

The breadth and scale of these changes — which, because of their national scale, generally affect more providers and beneficiaries than Innovation Center and MA efforts — could provide unique insights into how Medicare’s regulatory structures could be modified to improve beneficiary care. If CMS releases its findings to the public (as it does with Innovation Center payment model demonstrations), the results could inform future legislation and enable stakeholders to make meaningful contributions through the rulemaking process.

CMS has a window of opportunity to treat the current situation as a large-scale demonstration of how policy changes could affect the cost and quality of care. Sufficient Medicare claims data are available to begin to assess effects on cost of care in aggregate and by characteristics such as type of service, geography, and groups of beneficiaries. CMS also could begin to examine some population health quality measures, such as changes in the rates of hospital readmissions and unexpected emergency room visits.

Additional data, such as which providers and beneficiaries made use of the flexibilities as well as trends in service use, also could contribute to policymakers’ decision-making. Ideally, these initial findings will help answer the following questions:

- Why did Medicare providers and beneficiaries respond as they did?

- How can CMS offer an array of access options so that Medicare benefits are flexible enough to account for the various needs and limitations of all beneficiaries? For example, if audio-only telehealth services increased during the emergency, was this because providers or beneficiaries lacked access to audio/video technology? Or for other reasons?

- How did changes in the use of services that were permitted or expanded during the emergency affect quality of patient care? For example, if audio-only telehealth services increased during the emergency, did outcomes for patients who used these services differ from those for patients who used audio-video telehealth or in-person visits?

- Did use of these newly permitted or expanded services increase throughout the country or did different regions or markets make different decisions? If the response differed by region or market, what drove those decisions and how was beneficiary care affected?

- How did providers ensure all their patients had adequate access to care, whether by making use of newly permitted or expanded services or by relying on existing services — regardless of individual abilities and limitations? For example, were people who were unable to use telehealth services able to access in-person visits?

Framework Questions for Future Policy Actions

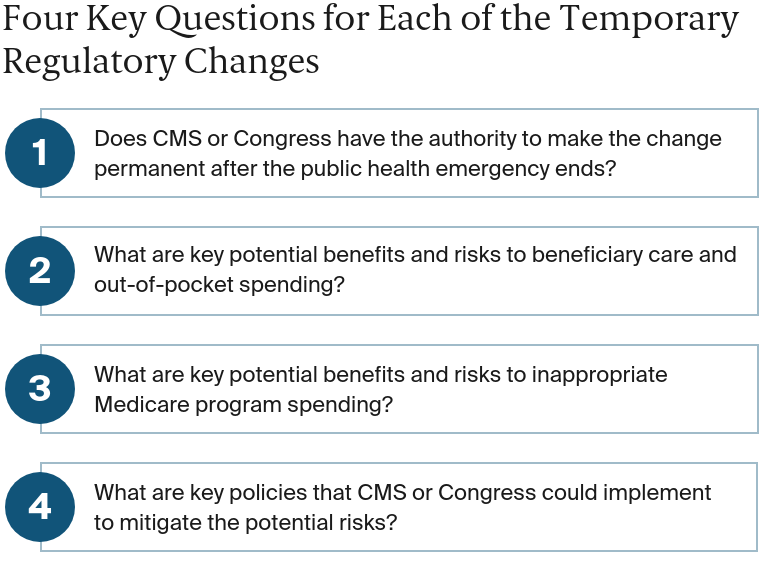

Recognizing that more research is needed to understand the effects of these policy actions, we offer a framework for policymakers to use in considering whether to modify, extend, or make permanent pandemic-related regulatory changes to Medicare. To start, CMS and lawmakers could consider four key questions for each of the temporary regulatory changes.

Examples of How the Four Key Questions Might Be Answered

We focused our analysis on temporary regulatory changes that fall under the themes of alternate sites of care, benefits and care management, and telehealth. Telehealth changes are relatively well known and have received attention from policymakers and stakeholders. The changes that affect alternate sites of care and benefits and care management are less discussed but also may have potentially significant impacts to the Medicare program and beneficiary care.

Does CMS have the authority to make the change permanent after the public health emergency ends?

CMS has the authority to make many temporary Medicare changes permanent (see Appendix). Only a fraction of the total number of temporary COVID-19-related Medicare regulatory changes would require legislation to be extended beyond the end of the public health emergency.

What key potential benefits and risks to beneficiary care and out-of-pocket spending do the changes pose?

To answer this (and the remaining questions), CMS or Congress could undertake a benefit–risk analysis to determine which beneficiary care experiences could be affected by the particular change, or, in some cases, group of changes. For example, CMS could assess whether the change will permanently alter beneficiary rights, such as their ability to receive medical records in a timely manner from hospitals. CMS also could review how changes might affect beneficiaries’ ability to understand their care plan.

CMS could also evaluate how each policy change might affect beneficiaries by making it more challenging for them to access their benefits or by increasing their out-of-pocket obligations. CMS could also determine whether permanent changes to move more care to alternate care settings could lead to poorer-quality outcomes. Detailed data analytics could provide insights into whether actual outcomes are more reflective of potential benefits or potential risks.

What key potential benefits and risks to Medicare spending do the changes pose?

For this question, CMS could evaluate whether or not the changes led to an inappropriate increase or decrease in spending, both at an individual service level and across the total cost of care. Many of the Medicare policy changes, such as increasing flexibility around telehealth and waiving some out-of-pocket costs, could lead to greater overutilization and unnecessary spending. These same changes also could result in less spending across a total episode of care if more services are provided in lower-intensity settings and if beneficiaries receive more timely access to care. Many of the changes also carry a greater risk for fraud and abuse.

What are key policies that CMS or Congress could implement to mitigate the potential risks?

From this benefit–risk analysis, CMS and Congress could identify specific mitigation policies to answer this final question. For example, to manage the risk of increased fraud and abuse, CMS could rely on established policies and procedures employed by its existing programs, including outlier analysis and other strategies to identify providers that have a higher than expected use of services for further review.

To mitigate concerns about patient access and quality, CMS could implement policies that, for example, allow for site visits and the fast-tracking of responses to concerns raised by beneficiaries who receive services at these sites.

To help beneficiaries understand how regulatory changes affect how they access Medicare services, CMS could develop educational materials. For example, it could create information that describes how cost sharing operates for alternate sites and broadly distribute the materials through CMS communication channels and through its partners, such as State Health Insurance Assistance Programs (SHIPs).

Conclusion

In response to the COVID-19 public health emergency, CMS and Congress made an unprecedented number of legislative, regulatory, and subregulatory changes to the Medicare program. More than 200 of these actions are currently in effect and are likely to remain part of the Medicare program through the end of 2021.

Some of these actions could prove to be beneficial after the end of the public health emergency and could become permanent Medicare policies. If CMS were to capitalize on this unique opportunity by undertaking rapid, large-scale evaluations of the effects of the changes, the results could inform policymakers’ decisions about future actions. Such a substantial research effort would provide CMS and the new Congress with data-supported insights into the relative benefits and risks of each COVID-19-related action as they consider which policies should continue in the future.