Abstract

- Issue: As the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted traditional health care patterns and overwhelmed health care systems, hospitals freed up capacity by discharging patients to postacute care settings, including home health agencies.

- Goal: To understand the impact of the pandemic on traditional Medicare beneficiaries’ use of home health and whether these effects vary for Black beneficiaries, Medicare–Medicaid enrollees (dual eligibles), and beneficiaries identified as having high needs.

- Methods: Descriptive and regression analyses using claims data for Medicare beneficiaries without a COVID-19 diagnosis discharged from short-term acute care hospitals between 2017 and 2020.

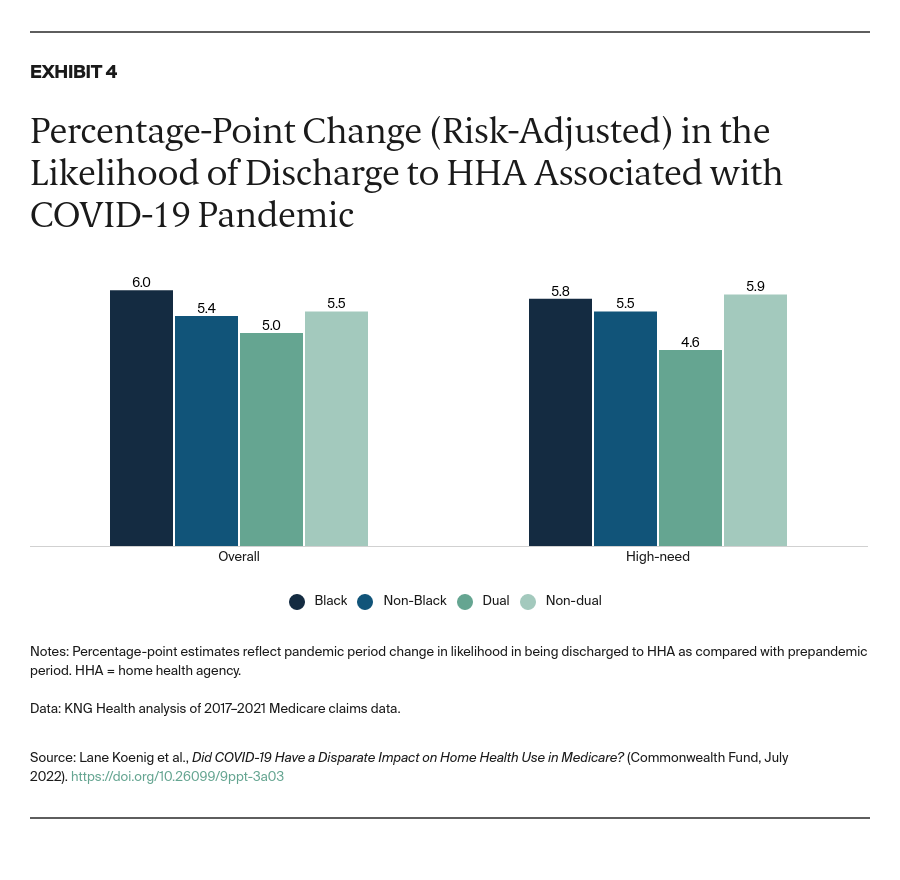

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Rates of patient transfers to home health care increased during the pandemic for all beneficiaries. Black beneficiaries saw a slightly greater increase in the likelihood of being discharged to home health care relative to non-Black beneficiaries, while dual eligibles saw a smaller increase relative to Medicare-only patients. Among high-need patients, we found less substitution of home health care for institutional postacute care, such as skilled nursing facilities, consistent with the greater care needs of this population. Although increased use of home health care may reduce Medicare spending, future policies would benefit from further analysis assessing the impact of greater home health use on outcomes for different types of patients.

Introduction

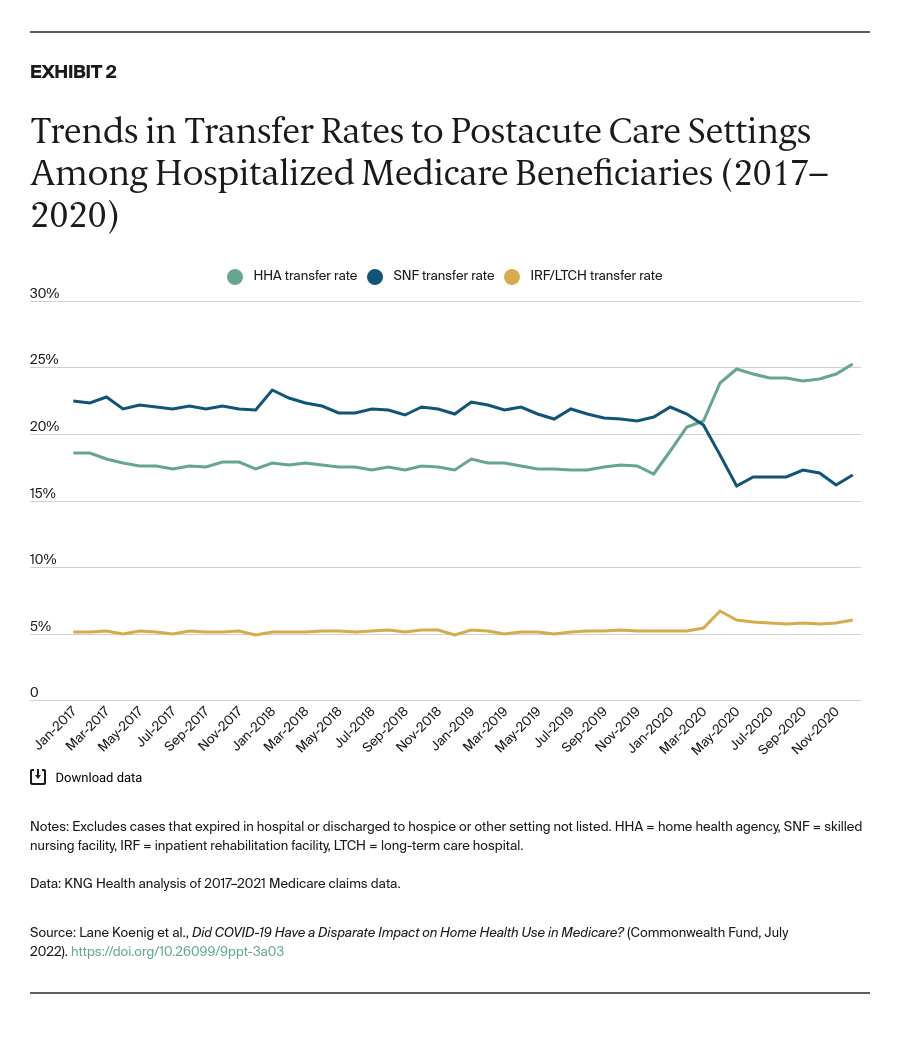

Since March 2020, hospitals have served as the frontline providers for the sickest COVID-19 patients, all while facing capacity constraints and staffing shortages. To free up capacity early in the pandemic, hospitals discharged COVID-19 and other patients to postacute care (PAC) providers, including home health agencies (HHAs), skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities, and long-term-care hospitals.1 To facilitate these transfers, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services waived certain regulatory requirements, including PAC patient eligibility criteria (Appendix Table A1). While SNFs (which are commonly colocated with nursing homes) experienced decreased utilization because of high COVID-19 transmission and mortality rates in nursing homes, the relative use of home health rose. This increase was likely driven by a preference for home-based care and by the waivers, which expanded access to HHA services.2

In this brief, we examine the pandemic’s impact on use of HHAs and other PAC providers following a hospitalization among traditional Medicare beneficiaries (those not enrolled in Medicare Advantage). The pandemic has highlighted significant disparities in access to care and patient outcomes, and we aimed to understand whether COVID-19 had a disparate impact on use of PAC following a hospital stay.3 We focus particular attention on PAC use among Black beneficiaries, Medicare–Medicaid enrollees (dual eligibles), and those with high needs, defined as the disabled, frail, or chronically ill.4

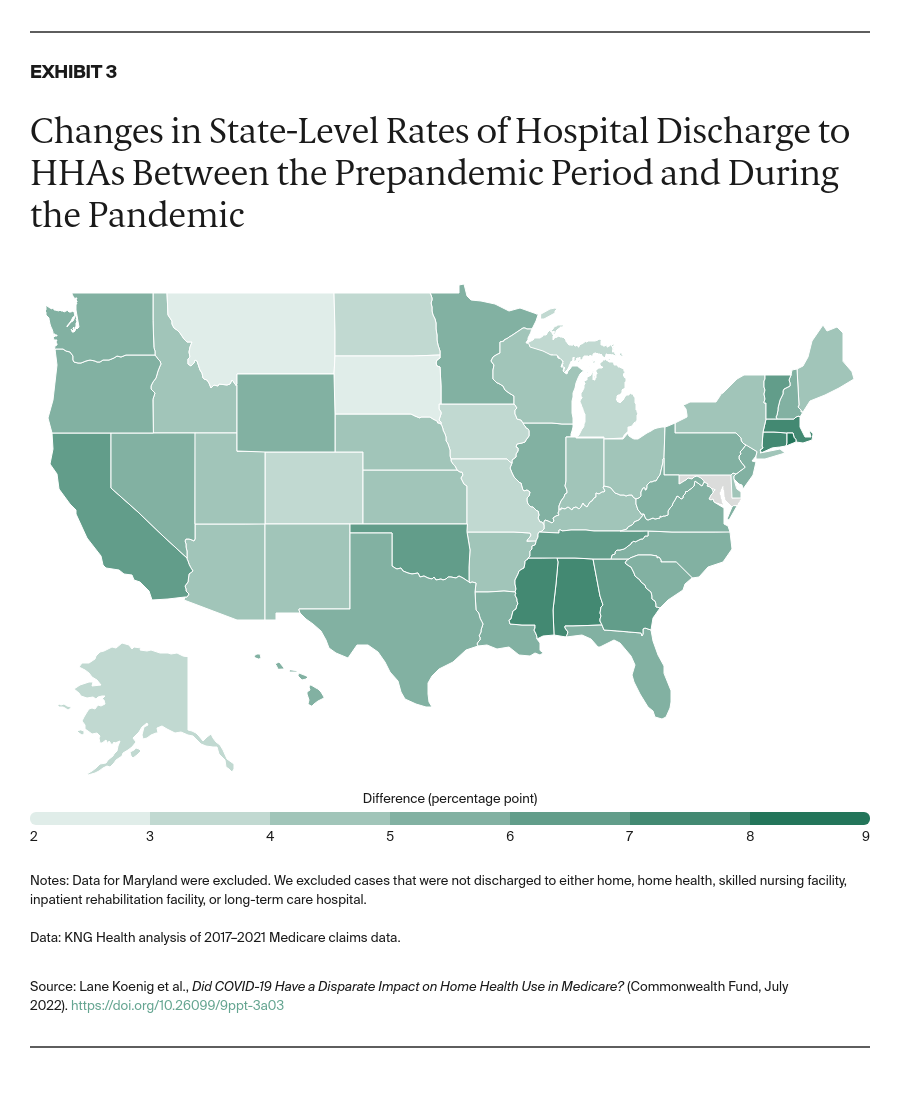

We first examine PAC use prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and then analyze how these patterns changed during the pandemic. Next, we quantify the risk-adjusted impact of COVID-19 on HHA and SNF use as well as on the use of high-quality HHAs. Because the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with payment reform that introduced changes to how Medicare compensates HHAs and SNFs, we attempt to control for the impact of these regulatory changes on PAC use patterns.

Findings

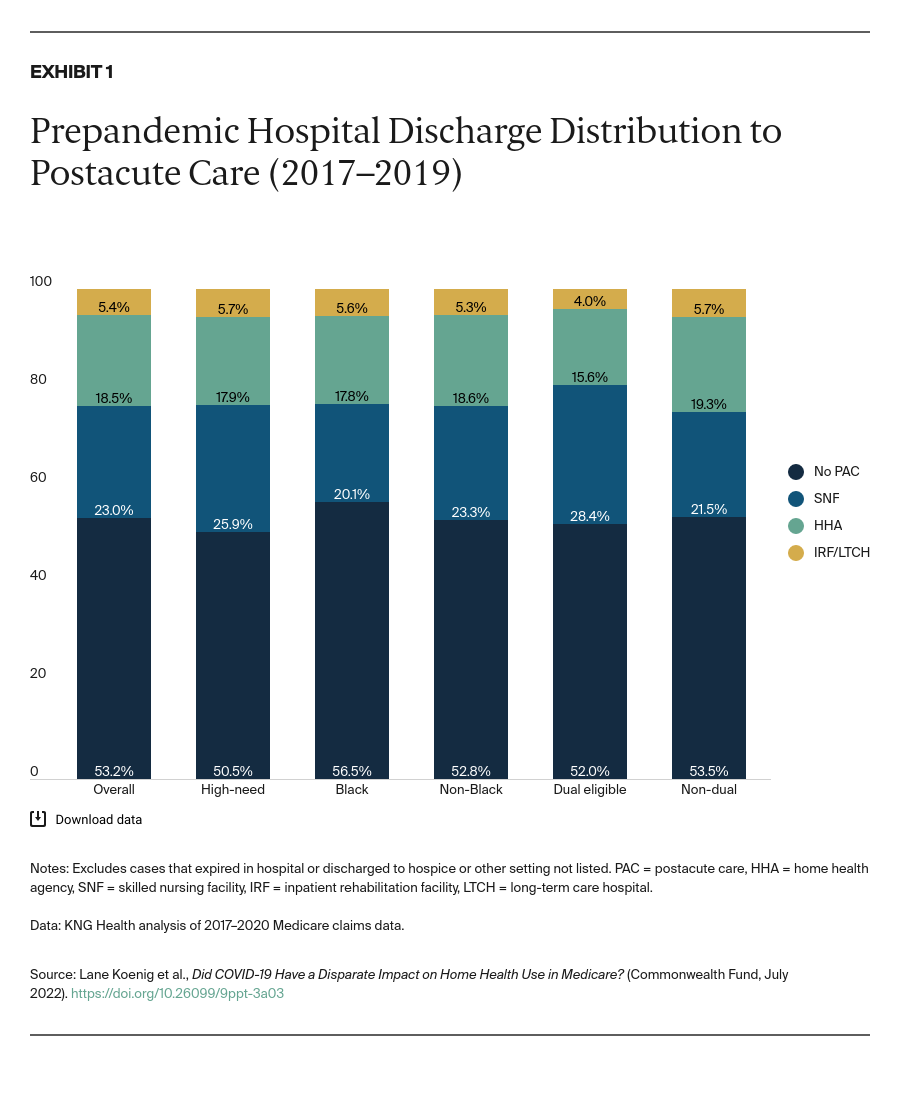

Variations in Prepandemic HHA and SNF Use Among Traditional Medicare Beneficiaries

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 53 percent of hospital discharges received no PAC (Exhibit 1, from 2017 to 2019). The most common setting for postacute care was a SNF, followed by home care through an agency. Black beneficiaries were less likely to be discharged to a SNF or HHA than non-Black beneficiaries and more likely to receive no PAC. Dual eligibles had materially higher rates of SNF use than people not dually eligible and were less likely to go home without any PAC.