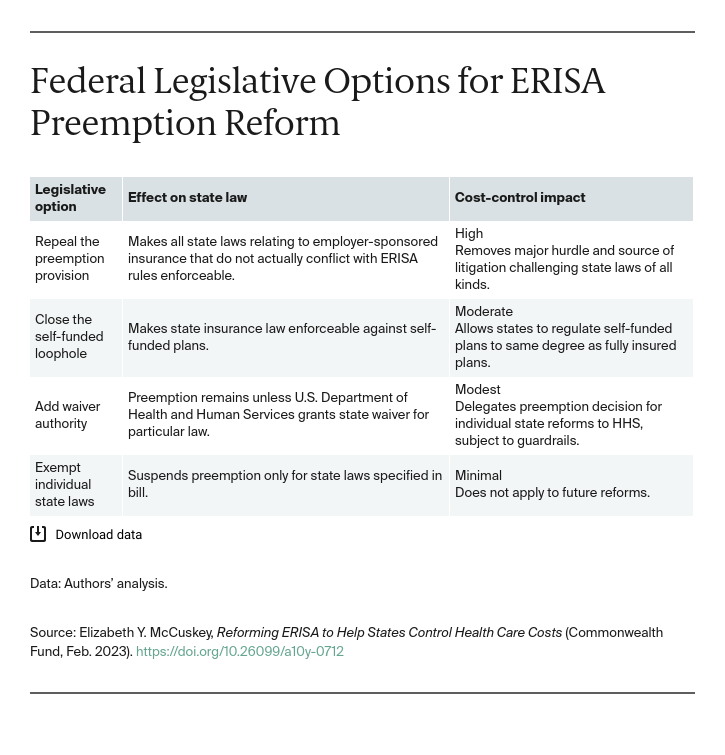

Repealing the preemption provision. This option would not eliminate preemption entirely but would limit the scope of preemption to only those state laws that actually conflict with ERISA’s rules, rather than “any and all State laws” that “relate to” employer-sponsored benefits. Similarly, Congress could enact new federal law that expressly supersedes or replaces ERISA with a different version of preemption.8 Though Congress in 1998 considered repealing the preemption to permit patients to sue plans, that proposal would have retained the broader “relate to” preemption for other insurance-related regulations.9

Closing the self-funded loophole. As a more moderate measure, Congress could close the ERISA preemption loophole for employer self-funded health plans. ERISA allows states to enforce their insurance regulations, despite the federal preemption for employer-sponsored benefits. For health insurance benefits, about 36 percent of employers buy their plans from insurers. These “fully insured” plans must abide by state insurance law. The remaining 64 percent of employers establish “self-funded” plans in which the employer assumes most of the financial risk and relies on third-party contractors to help design and administer the benefits.10

Though ERISA does not differentiate between these types of plans, the Supreme Court in 1990 interpreted ERISA’s language “to exempt self-funded ERISA plans from state laws that ‘regulat[e] insurance.’”11 Congress could change this through a “statutory override.”12 The year after the Supreme Court opinion, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D–Vt.) introduced a bill that would have lifted preemption “with respect to . . . the State’s authority to include self-funded employee welfare benefit plans in a health insurance reform effort.”13 It did not pass.

Adding waiver authority. Congress could give the administering agencies the power to suspend ERISA preemption for states on demand, creating a statutory waiver process. This modest change has been a popular feature in legislative proposals. During the past 30 years, Democratic legislators have proposed several versions of federal legislation to help states pursue comprehensive reforms and test models of universal coverage. These state-based reform bills often consolidate federal funding from existing programs and permit states to use these funds for universal care plans without the usual strictures of federal law. Typically, states must apply to a federal agency (usually some combination of the Departments of Health and Human Services and Labor, as well as the Internal Revenue Service), submit a plan for reform, and seek the Secretaries’ approval.

Recognizing that ERISA preemption prevents states from reaching some aspects of employer-sponsored coverage, the state-based reform bills have often (but not always) included a provision for waiving ERISA preemption.14 In the decade leading up to the Affordable Care Act, for example, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) and Rep. John F. Tierney (D–Mass.) introduced numerous versions of the “States’ Right to Innovate in Health Care Act.” That legislation would have created a process for states to apply to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) for federal “demonstration grants” to implement plans for a statewide “cost-effective delivery system of universal, comprehensive health care with simplified administration.” It also proposed to give HHS the authority to waive ERISA preemption for an approved state plan.15 It did not pass.

Republican proposals that failed during the same era did not touch ERISA preemption and tended to focus on ways to offer health insurance across state lines, subject to fewer federal and state requirements.16

Exempting individual state laws. As the most minimal change, Congress could suspend ERISA preemption only for specific state laws, creating an exemption. Hawaii is the only state that has a federally enacted exemption, which Congress passed in 1983 to save the state’s employer mandate from ERISA preemption.17 Bills introduced in the 1990s proposed exemptions for reforms in Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, and Washington but failed to pass.

Opportunities for ERISA Preemption Reform in the ACA Era

Since the ACA’s passage, efforts to address the ERISA preemption have again gained some momentum. Options include using State Innovation Waivers, passing the State-Based Universal Health Care Act, and enacting an ERISA preemption waiver.

State Innovation Waivers. The ACA enacted a federal employer mandate and established uniform standards for health insurance, but many of the ACA’s requirements do not apply to ERISA plans.18 The ACA afforded states some flexibility to seek waivers of the ACA’s provisions to pursue new reforms under the Section 1332 State Innovation Waiver administered by HHS.19 The federal employer mandate is among the waivable provisions in the ACA’s State Innovation Waiver. But the ACA expressly disavowed any effect on ERISA preemption and did not include ERISA preemption among the waivable provisions.20 So, for example, a state could apply for a waiver of the ACA’s employer mandate and enact a state payroll tax on employers that did not offer coverage. But this play-or-pay provision, under certain circumstances in some jurisdictions, has been found to trigger ERISA preemption.21 Thus, the ACA gave states a stronger set of federal rules to build upon and some new flexibility, but it did not afford them any relief from ERISA preemption.22

When the ACA’s State Innovation Waiver became active in 2016, states mostly used it for reinsurance programs to shore up the individual market, rather than as a catalyst for more comprehensive state reforms.23 Under the Trump administration, however, HHS encouraged states to use the waiver program to undermine the ACA itself.24 The administration granted waivers that litigants argue contravene the “guardrail” requirements in the statute.25 The Biden administration reversed this controversial approach.26 This experience with the ACA waiver illustrates how much delegating the preemption decision to a federal agency invites uncertainty and political calculation into the determination.

State-Based Universal Health Care Act. Democratic representatives have recently proposed bills for an expanded ACA waiver program that would support state experimentation with universal coverage designs and would include the authority to waive ERISA preemption for these experiments. First introduced in 2015, the State-Based Universal Health Care Act (SBUHCA)27 “builds upon the ACA’s State Innovation Waiver” by giving HHS the ability to waive “numerous barriers that limit states’ ability to design true single-payer systems.”28 Most importantly, the waiver expansion in SBUHCA makes it easier for states to pool funds from existing federal programs (like Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program) and authorizes HHS to waive ERISA preemption.29

SBUHCA’s Waiver for State Universal Health Care is designed for states’ comprehensive reforms and not for more discrete “innovations” covered by the existing ACA waiver. As prerequisite to granting a waiver, SBUHCA requires the state demonstrate that its plan will provide coverage to all residents and its coverage will be “at least as comprehensive” and “affordable” as coverage under existing federal programs.30 The “all residents” coverage requirement in SBUHCA is more demanding on states than the ACA’s State Innovation Waiver criteria of covering a number of residents “comparable” to the number with coverage under the ACA.31 Thus far, after two more attempts, SBUHCA has received backing solely from Democratic lawmakers representing 16 states.32

ERISA preemption waiver. State legislators, meanwhile, have garnered some bipartisan support for ERISA preemption reform. In 2019, the National Council of Insurance Legislators (NCOIL), a bipartisan organization of state lawmakers serving on insurance committees, passed a resolution asking members of Congress to enact an all-purpose ERISA preemption waiver.33 Expressing their frustration that ERISA preemption threatens state reforms as modest as all-payer claims databases, NCOIL urged Congress to amend ERISA to allow the Secretaries of Labor and HHS to waive ERISA preemption for particular health reforms.34

Adding waiver authority directly to the ERISA statute would enable states to pursue a wider range of health reforms — including discrete cost-control efforts that are not part of comprehensive reform packages or otherwise within the ambit of ACA provisions. Permitting a waiver of ERISA’s preemption provision also would allow states to add to existing federal protections while preserving ERISA and the ACA. In this way, it aligns with the Biden administration’s plans to build on the ACA.35

An ERISA preemption waiver is, by definition, budget-neutral for the federal government because ERISA does not provide any federal funding that could pass through to the states. But a statutory waiver program — as opposed to a law altering the preemption itself — would make the availability of waivers depend somewhat on administrative discretion. So, for example, under an ERISA waiver provision, a state could seek a waiver of ERISA preemption for an all-payer claims database that included collection of self-funded plans’ data, a practice currently preempted by ERISA’s loophole for self-funded plans. A state also could apply to waive preemption for a play-or-pay provision to tax employers who do not offer coverage. Although that provision should withstand an ERISA preemption challenge, having a federal preemption waiver would save the costs of litigation.

Though modest in its potential impact, a statutory waiver provision may be more politically palatable because it does not automatically affect all employers, and it offers stakeholders an opportunity to weigh in on the potential impacts of proposed waivers.

Conclusion

Calls to relieve state health reforms from ERISA preemption have been around for more than 45 years. Even the most modest changes have failed to pass thus far. With the current divided federal government, an ERISA preemption waiver presents an opportunity for federal legislators to ease the way for states to pursue urgently needed cost-control efforts while larger reforms likely stall in Congress.