The article is part of a partnership between the Commonwealth Fund and the Bassett Research Institute in Cooperstown, N.Y., to explore innovative approaches to the health care challenges facing rural communities across the United States.

Introduction

In 2016, just months after taking charge of Dayton General Hospital, a 25-bed critical access hospital in the southeastern corner of Washington State, Shane A. McGuire came upon a nurse who was tossing referrals from outlying hospitals into a trash can. “It’s just someone wanting to unload their patients on us,” he recalls her saying.

As CEO, McGuire was intrigued. The hospital — part of the Columbia County Health System (Columbia), which also operates two rural health clinics and a nursing home in a county with roughly 4,700 people — had an average daily census of just 1.7 patients and the staff to care for far more.

McGuire learned the hospital received one to two requests like this each day from discharge planners at hospitals across the state, all wanting to know if Dayton General could take on patients who needed skilled nursing care but were hard to place. Some were homeless, many had mental health or substance use issues, and nearly all were covered by Medicaid, one of the lowest payers in the state. Without a place to go, these patients often remain in hospitals, filling beds that are needed during COVID surges, heat waves, and other emergencies.

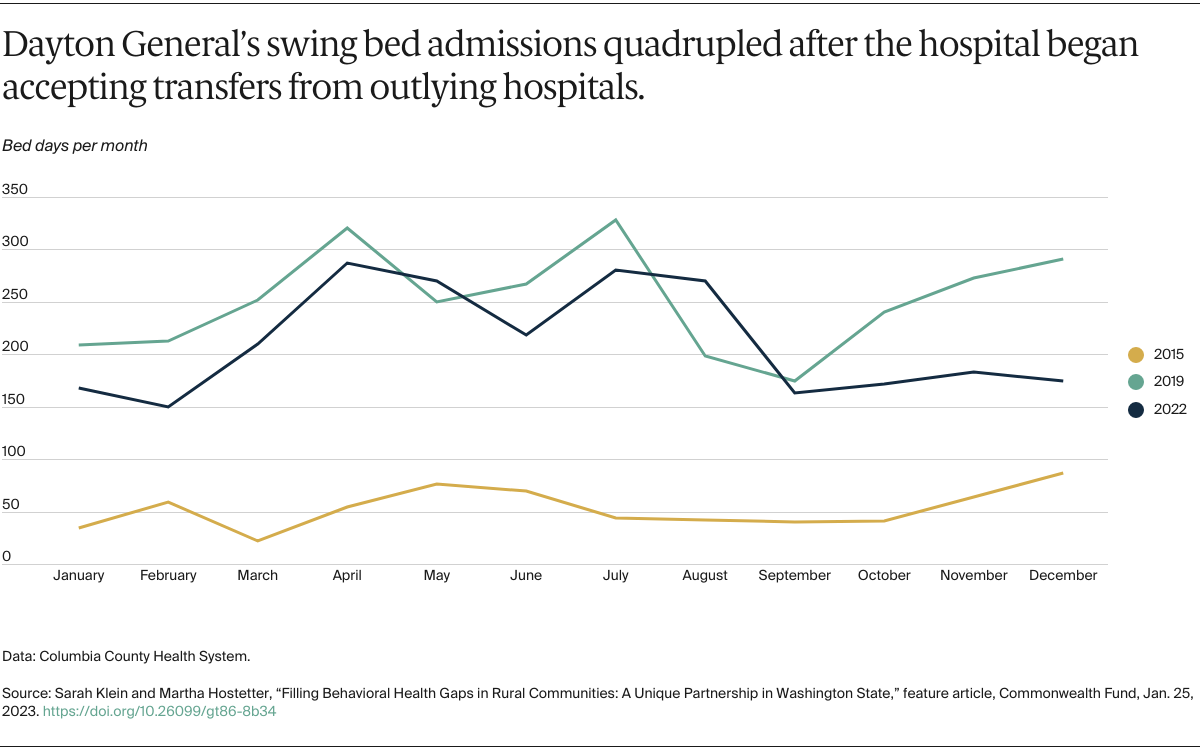

Like other critical access hospitals, Dayton General was in a position to help because it can dedicate some of its beds as “swing beds” for people needing rehabilitation. In rural communities, swing beds are often used for patients recovering from surgeries or those who require infused antibiotics to treat infections. Across the United States, the capacity of critical access hospitals often goes untapped. The median average daily census for a critical access hospital was 2.2 patients in 2020, according to data from the Flex Monitoring Team, a consortium of rural health research centers. The census for swing beds was even lower that year at 1.5 patients per day.

As McGuire and his staff began thinking through what it would take to honor these requests, he was also hearing about a pressing need for mental health services in his local community. Columbia’s rural health clinics had recently begun screening for depression as part of a patient-centered medical home program. A full third of patients were screening positive for clinical depression and “we weren’t doing anything about it,” McGuire says.

Part of the problem was that there were no psychiatrists in the county and the issues clinicians were seeing were not easy to address, even for the clinics’ newly hired social worker. “We were getting in a room with people who had experienced just horrific childhood events, some had posttraumatic stress disorder, and there was nowhere to refer them,” McGuire says. This workforce shortage is pervasive in rural counties: nearly two-thirds lack psychiatrists and nearly half lack psychologists.

Leveraging Rural Hospitals’ Strengths to Help Patients with Complex Needs

To build a continuum of behavioral health services, McGuire partnered with the University of Washington’s Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions Center (AIMS Center) in Seattle in 2017. The AIMS Center promotes the integration of physical and behavioral health services through its Collaborative Care model, which enables specialists to offer guidance to primary care and hospital-based providers as they manage behavioral health conditions. Two of its psychiatrists agreed to provide consultations to providers in Columbia’s rural health clinics, as well as its hospital and nursing home, and offer telehealth visits with patients as needed.

With this support in place, McGuire and his staff began making the rounds of vendor fairs at hospitals across the state. Their pitch — that Dayton General could provide acute care or skilled nursing services to patients at high risk of readmission — resonated with discharge planners who saw patients, particularly those with substance use issues, cycle in and out of hospitals and emergency departments. “They are tired of the revolving door. They want to see some intervention for these folks as well,” McGuire says.

As hospitals across the state took them up on the offer, Dayton General’s average daily census increased to 14 patients. Of those using its swing beds, nearly 60 percent have substance use disorders, including problems with methamphetamine, alcohol, and opioids. Many come from outside the community, putting distance between them and the environment or relationships that contributed to their substance use. “If you’re from Aberdeen, more than 350 miles away, the person who supplies you with drugs is not going to run to Dayton,” McGuire says.