The article is part of a partnership between the Commonwealth Fund and the Bassett Research Institute in Cooperstown, N.Y., to explore innovative approaches to the health care challenges facing rural communities across the United States.

Introduction

Medical emergencies are often rooted in missed opportunities: car trouble leads to a missed appointment; new symptoms aren’t noticed; or a patient leaves a clinic without fully understanding their doctor’s instructions.

These kinds of problems happen everywhere. But the odds are higher in rural communities — where patients tend to be older and sicker than their urban and suburban counterparts, and may be more geographically isolated — so there may be fewer people around to notice if they develop a problem. Rural residents must also travel longer distances to reach hospitals and clinics.

In some rural communities, community paramedicine programs are being used to extend the reach of health care providers. They send paramedics and other staff to peoples’ homes with the goal of stabilizing their health and avoiding the need for 911 calls down the line. Instead of responding to emergencies, community paramedics might visit people after an emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization to make sure they understand their treatment regimen or to assess safety risks in their homes. Some programs train paramedics to offer disease management tips or link people with social supports. “It's a real change in focus for paramedics,” says Gary Wingrove, president of The Paramedic Foundation. “Typically, they are thinking about how to take care of a patient's emergency in the next 30 minutes. As a community paramedic, they're thinking about the next 30 days and they’re working very closely with primary care and specialist physicians and others to develop care plans.”

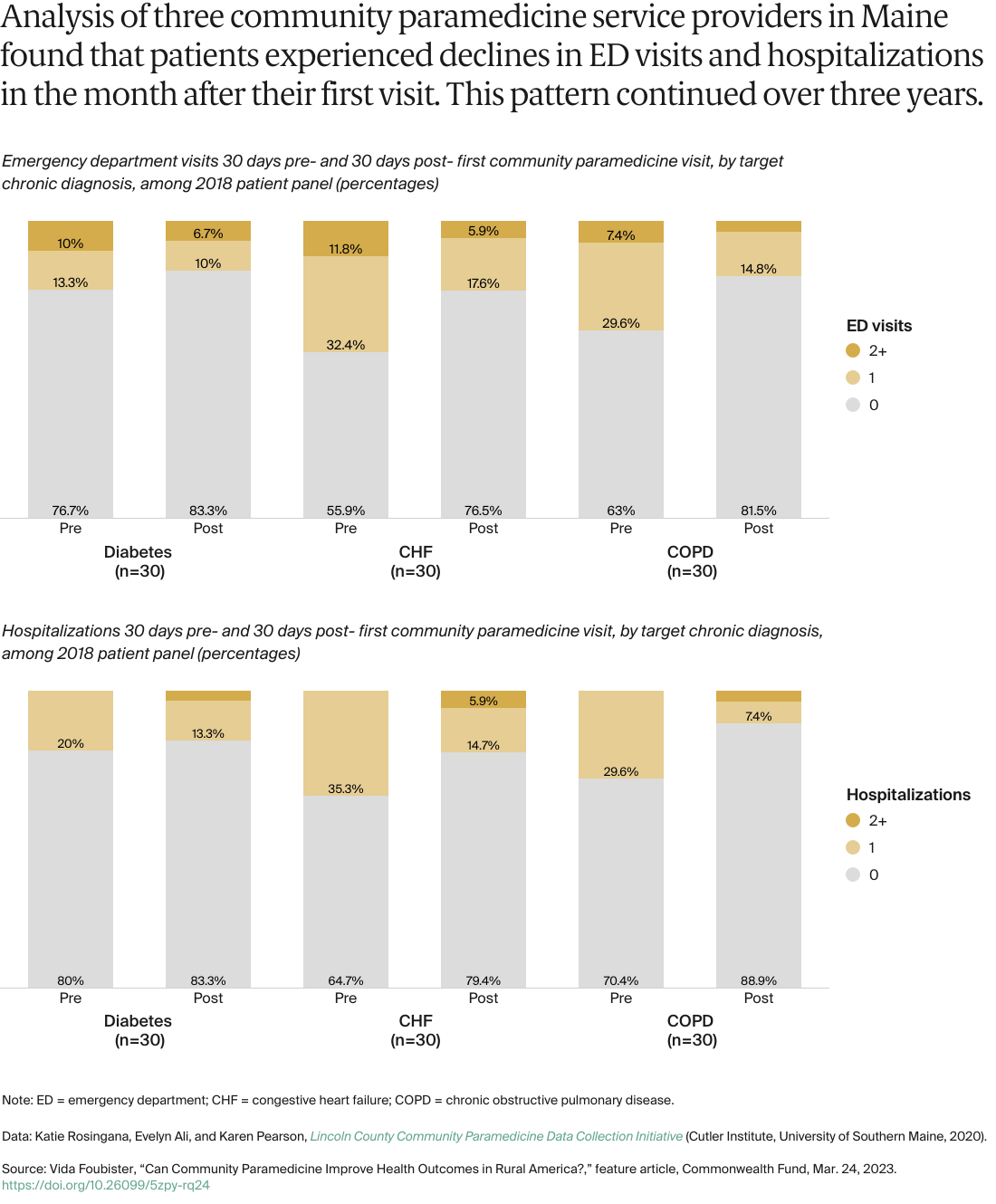

Community paramedicine programs date to the 1990s and have grown in number over the past decade. A 2017 survey found there are at least 129 programs in the United States, more than 40 percent of them serving rural areas. In this feature, we profile three community paramedicine programs that serve rural communities. The programs are supported by grants or subsidized by large health systems. They won’t solve workforce challenges in rural communities or the fragile financing of rural health care systems, but they are beginning to demonstrate success in helping people manage their conditions and avoid ED and hospital use. Advocates hope they may attract the interest of payers and providers engaged in value-based contracts that hold providers accountable for the quality and total costs of care.

Helping People Manage Chronic Conditions

In 2019, Rozalina G. McCoy, M.D., M.S., medical director of Mayo Clinic Ambulance’s Community Paramedic Service, had a question. She knew that many people with diabetes call 911 when their blood sugar drops to an unsafe level (hypoglycemia), and about half wind up being taken to the hospital. But what happens to the other half? McCoy partnered with paramedics to find out. “We found that people who are not transported have a nearly twofold higher rate of having a recurrent hypoglycemic event within 30 days,” she says. “They call the ambulance, paramedics come and reverse the hypoglycemia with oral or intravenous glucose, but then they leave because the patient is better and doesn’t want to go into the ED. But then nothing happens to their treatment regimen. So they keep having the same problem, even though it can be prevented.”

To disrupt this cycle, McCoy and her colleagues applied for a grant to create a community paramedicine program for patients with diabetes. Mayo Clinic is known for its destination medical center in Rochester, Minn., but the health system also serves rural communities in southern Minnesota, western Wisconsin, and northern Iowa. Back in 2016, one of Mayo’s critical access hospitals in northwestern Wisconsin had begun testing whether home visits from paramedics could benefit patients who were high utilizers of emergency and acute services in its home county. The paramedics followed physicians’ orders to perform tests, review medications, and provide other services. Over a six-month period, the program was associated with a 59 percent reduction in ED visits, and it received positive ratings from clinicians.

Armed with these promising results, McCoy and her team launched a trial in 2020 to test whether support from community paramedics could improve outcomes for rural patients with diabetes who have high blood glucose levels and visit the ED or hospital for any reason. Then, in 2021, they started another trial, this time focused on patients who become hypoglycemic and call 911 or seek medical care for it in the ED or hospital.

In both studies, Mayo Clinic community paramedics visit patients at their homes to identify the reasons for their low and high blood sugars. With support from McCoy, the paramedics then partner with the patient, their care partners, and their clinical teams to optimize patients’ insulin doses, reconcile their medications, promote good nutrition and physical activity, and improve adherence to glucose monitoring and medication. They also help people find food banks or other community assistance programs as well as programs that can reduce the costs of their diabetes medications and supplies.

Over time, Mayo Clinic’s community paramedicine service has grown to support patients with heart failure, cancer, and a range of other chronic conditions, as well as those needing wound care. Community paramedics have been trained to use ultrasound to identify and diagnose patients with pneumonia or heart failure and can perform urgent lab tests at the point of care. “EMS clinicians have an incredibly wide skill set,” says McCoy. “They learn quickly and adapt to new situations and clinical needs.” Mayo Clinic’s community paramedics need at least two years’ experience as a paramedic and must complete specialized training to become proficient in the services offered. Most will also hold academic positions in the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine. “It’s not just more work and more responsibility for the community paramedics compared to being a paramedic,” says McCoy. “This role affords them more autonomy, respect, and ability to contribute to the health care system and to the health of our patients.”

McCoy says the costs of community paramedicine are modest: they include the salaries of community paramedics and the cost of supervision, vehicles, and gas. Thus far, services have been available to patients who need them at no cost and without going through insurance, in part because of limited reimbursement for community paramedic services by different insurance plans. However, as the community paramedic model grows and evolves, McCoy is hopeful that insurance plans will recognize the immense value they bring to patient care and begin reimbursing these services.