Pursuing More Favorable Contracts with Payers

With a lower volume of patients, rural hospitals can be at a disadvantage when negotiating with vendors and payers. The Louisiana Independent Hospital Network Coalition formed a group purchasing organization to secure better rates for members, negotiating the purchase of food services, laundry, radiology equipment, and other services and supplies.

Several of the rural partnerships have tried to negotiate better deals within the constraints of federal and state antitrust laws that bar independent hospitals from comparing information about what they’re paid by insurers and other forms of collaboration that could be construed as efforts to hinder competition.

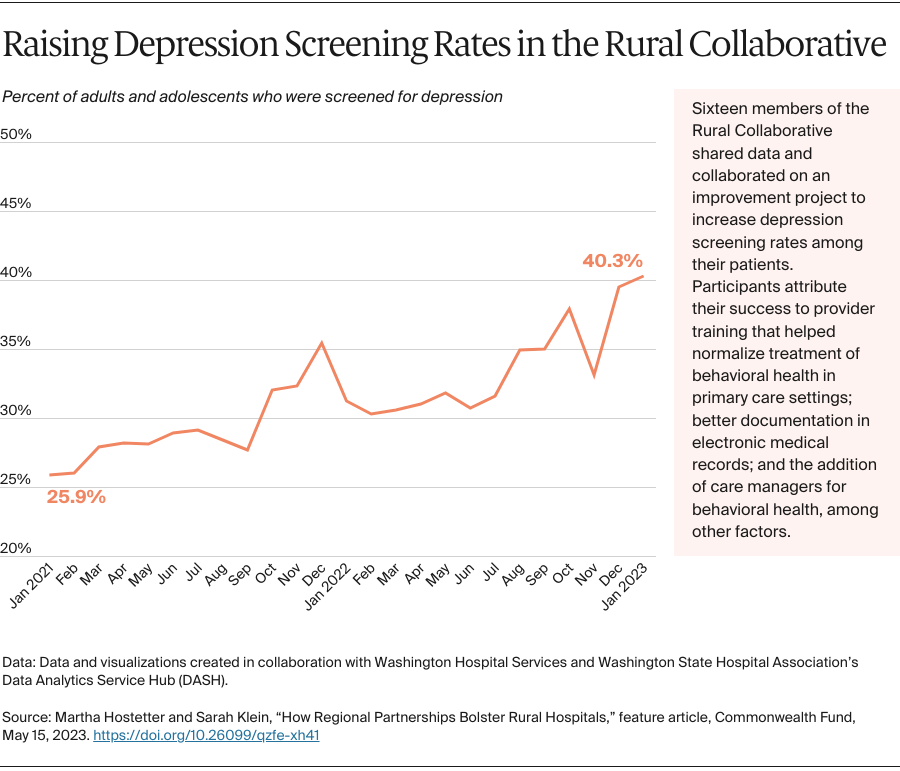

Hospitals in some states have more flexibility than others. Washington State’s public hospital districts, created in 1945 to expand access to care in rural areas, allow members of the Rural Collaborative to work together in certain ways, including by forming agreements to better serve patients. “It’s phenomenally helpful,” Prystowsky says. Her members can also jointly contract with health plans, helping them negotiate better terms and stay on top of changes. “It takes a lot of time and skill for each hospital to carefully read payer contracts,” she says. “We’re able to centralize that work. When a payer changes a policy, we let all our members know right away and can swiftly advocate for appropriate changes.”

The Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative took another approach. In 1996, it obtained a “business review letter” from the U.S. Department of Justice that allows members to work together on health insurance contracts. This means that staff of the cooperative can, for example, review and help negotiate language in managed care contracts on behalf of its 44 members and offer consultation on how members are reimbursed for services such as swing beds, used for patients needing rehabilitation. “We can do things that add substantial value for our members, short of sharing hospital-specific reimbursement or organizing a boycott,” says Tim Size, CEO.

Participating in Value-Based Payment Arrangements

The collaboratives can make it easier for rural hospitals to participate in accountable care organizations (ACOs) or other value-based arrangements that enable providers to share in the savings that result from improving care for a defined set of patients. Such arrangements can be fraught for rural providers, given their low volume: a handful of catastrophic cases can not only negate any savings, but incur losses for the ACO. By banding together with other hospitals, rural hospitals gain sufficient patient volume to minimize that risk. Joining together also gives rural providers access to performance benchmarks and guidance on ways to improve.

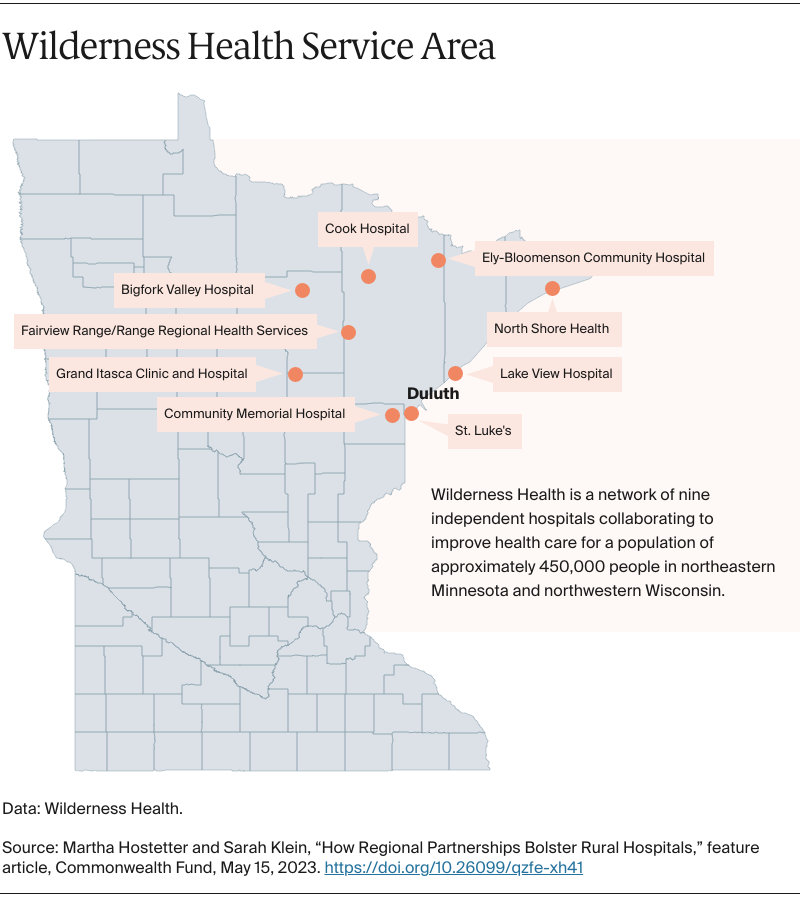

In Minnesota, Wilderness Health formed an ACO in 2015 with the state’s Medicaid agency, which gave hospitals access to data to see “gaps in care and who’s using the emergency department for primary care,” says executive director Cassandra Beardsley. “We used that information to build our care coordination approaches,” she says.

The initial contract called for member hospitals to receive shared savings or incur losses based on their ability to meet quality benchmarks and control costs. Although the ACO achieved savings in its third year, generating revenue that supplemented fee-for-service payments, members asked the state to replace the shared savings and losses approach with a per member per month amount that would be added to fee-for-service payments. “Without that, it’s hard to make sure you’ve got resources for care coordination,” says Beardsley. The per member per month fees, totaling more than $1.8 million over the past four years, are adjusted based on patients’ health and social risks. Wilderness Health has used the funds to hire a care navigator that works with member hospitals, and individual hospitals have hired care coordinators, clinical pharmacists, occupational therapists, and other staff to help patients manage their chronic conditions.

In 2015, 20 members of the Illinois Critical Access Hospital Network formed an ACO, the Illinois Rural Community Care Organization, to join the Medicare Shared Savings Program. In 2017, the ACO signed a contract with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois to manage commercially insured patients, earning $4.4 million in shared savings in 2019 and 2020.

In 2021, 18 hospitals in the Illinois ACO launched a venture with the managed care company Centene to coordinate care for Medicare Advantage patients. Centene brings financing and data analytics to the partnership, while the local hospitals work to create “stickiness,” that is, to build long-term relationships with patients so they stay in their communities for care. “Patients must go to an urban center of excellence for some of the things they need,” says Trina Casner, CEO of Illinois’ Pana Community Hospital and chair of the board of the ACO. “But we are working on finding the right support to help them stay local, which is not only beneficial to them, but also to the local providers.”

Promoting Community Development

Ultimately, rural hospitals are only as strong as their communities. When hospitals close, it’s often after years of rising unemployment rates, declining per capita incomes, and depressed housing markets in the surrounding counties. And their closures often worsen economic conditions as jobs leave the community.

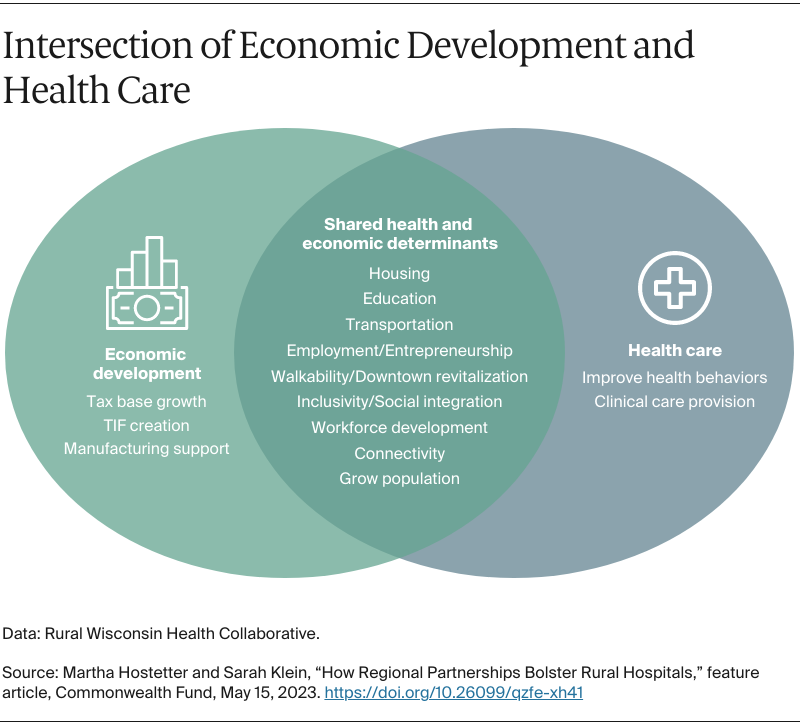

The Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative recently launched an economic development program to offer technical assistance to members about ways to invest their community benefit dollars and other resources to promote affordable access to housing, childcare, broadband, and other infrastructure. “Ten years ago, we needed jobs in rural Wisconsin,” says Marie Barry, the cooperative’s director of community economic development. “Today, we have jobs but we don’t have people. We don’t have places for them to live. We don’t have people to watch their children while they go to work.”

Members have had some success in building affordable internet access, something one of four rural residents lacked as of 2021. Several federal programs offer grants to help rural communities develop broadband, but these communities may not have capacity to apply for them. “One of our small rural counties just hired its first county administrator,” says Barry. “Prior to that they’d had a county board with part-time members who then had to go back to being farmers or bankers or nurses. People from other areas of the country aren’t always aware of this lack of administrative capacity in rural communities.”

To help, one of the Wisconsin cooperative’s member hospitals dispatched its chief information officer to join a countywide task force that secured $4 million in funds for broadband. In other parts of the state, hospitals joined with schools and county governments to fund an angel account that pays for low-income residents to have Starlink broadband, which relies on low-orbit satellites to provide access in communities that lack internet towers or fiber optic cables.

Coop members are also working to increase access to affordable housing in their communities, using community benefit dollars and mechanisms like land trusts to finance new developments. The CEO of Door County Medical Center became interested in this issue after learning some of his own staff couldn’t find housing: one of his X-ray technicians was living in a storage shed, and a nurse was living in the back room of a yoga studio. Among other efforts, Door County Medical Center helped commission a market study to identify the housing gaps in the area. The CEO has also voiced support for a new, multifamily housing development and connected developers to local investors.

You can’t really have an economic development plan without your local hospital.

Jessica Canning

Executive director, Louisiana Independent Hospital Network Coalition

Lessons

Regional health care partnerships aren’t a panacea to the many problems facing rural providers. For example, while they’ve often been able to share staff, they’ve had little success in helping hospitals recruit new staff — a problem likely to get worse with the looming retirement of baby-boomer clinicians. Still, by joining together, members have been able to secure grant dollars, pilot local solutions, and dip their toes into value-based payment arrangements. Their experiences point to policy changes that could strengthen rural providers.

Medicaid expansion and other supportive state policies. While rural hospitals in many southern states have closed, Louisiana has seen only two hospitals close since 2005. The state’s decision to expand Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act has likely helped, reducing the burden of providing uncompensated care to uninsured patients. Louisiana’s Rural Hospital Preservation Act has also increased Medicaid rates. Leaders have prioritized rural health care, according to Canning: “Our state government is focused on not letting rural hospitals close.”

Giving rural hospitals flexibility to work together. If more states created protections like those in Washington State, more rural hospitals could work together to negotiate better contracts with payers. The protections would need to be set up in ways to prevent hospitals from engaging in anticompetitive behavior.

Policies to encourage hospitals’ investments in rural communities. Critical access hospitals have a financial disincentive for investing in certain types of programs that benefit their communities, like Meals on Wheels programs or childcare, because this requires allocating some of their overhead costs to these programs even when they do not need much administrative support. “Doing so can lead to a loss of reimbursement for hospitals since hospitals are paid by Medicare and Medicaid based on their costs of providing clinical care,” says Barry of the Rural Wisconsin Health Cooperative. “This can deter hospitals from taking part in nonclinical programs that benefit their communities.”

Value-based payment arrangements that make sense for rural providers. Research suggests that rural hospitals’ participation in ACOs that involve shared savings from fee-for-service payments has not increased their operating margins. Others have pointed out that small rural hospitals with low patient volume are unlikely to reap gains from these contracts because there are few opportunities to generate savings. “It’s like trying to squeeze blood from a turnip,” says Lauren Hughes, M.D., M.P.H., M.Sc., associate professor of family medicine and state policy director of the Farley Health Policy Center at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Hughes notes that rural providers would benefit from population-based payments that provide them with predictable revenue streams and flexibility to care for their patients.

Harold Miller of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform argues that rural providers need “standby capacity payments,” that is, monthly fees per patient to sustain emergency care and other essential services regardless of how many services patients receive. Such payments could also enable rural providers to shift away from inpatient care and planned procedures, where demand is low, to offer chronic care management, home-based care, and other services that could benefit their sicker and older patients.

“Providing care in rural America is different than providing care in urban America,” says Casner of Illinois’ rural ACO. “We're the bread-and-butter stuff that most people will need at some point in their lifetime.”