This case study is the fourth in a series profiling how primary care clinics — federally qualified health centers, independent clinics, and clinics that are part of large health systems — are meeting the needs of low-income patients who often lack the resources to stay healthy. The series profiles clinics that exhibit some or all of the following attributes:

- Medical home capabilities as a foundation

- Multidisciplinary teams with community health workers

- Integration of primary health care with public health, social services, and behavioral health

- Using data to manage and improve patient care and clinic performance

- Geographic empanelment, looking at health needs across a region and using risk stratification to target interventions

- Proactive patient and family engagement to address physical, social, and cultural barriers to care

- Leveraging of digital tools to improve health.

This case study profiles two clinics: Thomas Chittenden Health Center in Vermont has a multidisciplinary care team that works to address patients’ physical health, behavioral health, and social needs. Nurse practitioners at Wright & Associates Family Healthcare in New Hampshire seek to develop trusting relationships with patients while providing low-cost, comprehensive primary care.

Introduction

In 1927, the Harvard Medical School professor Francis Peabody, M.D., reminded the graduating class to make time to listen to patients’ stories and offer the bedridden sips of water or adjust their sheets. These small gestures, he explained, help earn patients’ trust, and trusting relationships are key to healing. His advice — “the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient” — is part of the medical school’s curricula today.1

Many of the medical students who choose to go into primary care today do so because they want to develop these sorts of personal relationships with patients. But pressure to meet productivity targets and administrative burdens often prevent them from doing so. Half of primary care clinicians say they are burned out, compared with a third of physicians in fields such as orthopedics, psychiatry, or general surgery, and fewer medical students choose to go into the field each year.2

This case study offers examples of primary care clinicians who have remained independent out of a desire to deliver care the way they want to, including spending ample time with their patients. The practices are not owned or managed by health systems, nor are they part of safety-net clinics. Many independent primary care clinicians opt to open practices in poor communities, where they find gaps in the market and feel a sense of mission to serve.

We’re focusing on independent primary care clinicians, including physicians, nurse practitioners, and their care teams, because they are often absent from debates about how to reform U.S. health care. We’re also focusing on primary care because there is widespread agreement that improving population health and reducing health care spending requires that we get much better at helping people stay well and identifying and treating problems as early as possible.

This case study explores how two independent primary care practices, one in New Hampshire and one in Vermont, are leveraging their independence to tailor services to patients who struggle to afford care, have chronic physical or behavioral health conditions, and/or need help finding social supports. We also explore the struggles these practices face in sustaining their small businesses while attempting to benefit from new value-based payment models.

The two practices offer different illustrations of independent primary care. The one in Vermont is quite large and has benefitted from state policies supporting multidisciplinary team care. By contrast, the practice in New Hampshire has less state support; it has kept costs low by fielding teams of nurse practitioners and medical assistants, who work together to meet patients’ needs.

Thomas Chittenden Health Center

Thomas Chittenden Health Center — the largest, single-site independent primary care practice in Vermont — recently celebrated its 50th anniversary. With five physicians, three nurse practitioners, and four physician assistants, it provides 35,000 visits a year to some 18,000 people. About half are covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or both and most of the rest are covered by private insurance. The clinic offers visits seven days a week and clinicians take calls to answer questions after hours. During the first few months of the coronavirus pandemic, two of the practice’s clinicians offered in-person visits and the rest offered virtual visits.

Located in the small town of Williston, a short drive from Vermont’s largest city of Burlington, the practice serves multiple generations of families that include University of Vermont professors, farmers, artists, and people struggling to get by. “We have a fair number of patients who have three generations in one home, who live paycheck to paycheck if they have a paycheck,” says Joe Haddock, M.D., medical director.

Progressive State Policies and Capitation Payments Support Extra Services

In recent years, supportive state health reforms and capitated contracts have enabled Chittenden to expand its care team and services.

Since 2018, the clinic has received capitated payments to provide care for about 30 percent of patients (including those covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and private marketplace coverage) through an all-payer pilot led by OneCare Vermont, an accountable care organization (ACO) involving nearly all the state’s hospitals and most of its medical practices. In 2019, the rate was set at $33.50 per member per month, plus a $3.25 per member per month care management fee. The additional funds from capitated payments — representing a 10 percent increase in revenue — as well as the more predictable revenue stream have enabled Chittenden to give primary care clinicians their first raise in a decade. Enhanced, stable funding also has allowed the practice to hire more staff and offer additional services, including nutritional counseling and psychiatry to all patients, regardless of whether their insurance covers those services.

Joe Haddock, M.D., medical director of Thomas Chittenden Health Center, has deep roots in the Williston community. In addition to his medical practice, he runs a sheep farm and plays guitar at his patients’ and neighbors’ funerals.

Capitated payments have helped sustain the practice during the pandemic, according to Haddock. “This program may be seen in a more favorable light by other practices after all this,” he says. Still, with 70 percent of the practice’s revenue tied to fee-for-service reimbursement, the practice is facing shortfalls as patient volume fell by about 9 percent during the first five months of 2020 and has not fully recovered. Chittenden has received federal support from the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), as well as CARES Act funding, to purchase protective equipment and pay for new cleaning and screening procedures. “So far, we have had no layoffs or significant reduction in hours,” Haddock says. “But the upcoming months may be more difficult, after using all the PPP funds.”

The practice also has benefitted since 2013 from Vermont’s Blueprint for Health, a statewide effort to improve health and reduce costs by fielding nurses, counselors, social workers, community health workers, and others to complement the work of primary care clinicians. At Chittenden, these staff members help patients manage their chronic conditions, find treatment for addiction and other behavioral health conditions, and connect with social supports. Their salaries are partially or fully paid for through the Blueprint, which is funded through contributions from public and private payers.

For example, Lisa Anderson, a social worker and care coordinator, offers services to patients who are identified as high risk based on their past hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits as well as clinicians’ knowledge of their medical and social circumstances. “Our care coordinator helps people stay out of the hospital by doing things like finding their medicine or helping them find a place to stay so they don’t have to sleep in a car,” says Haddock.

Funding Sources for Thomas Chittenden Health Center’s Care Team Members

Salary subsidized with funds earned through capitation pilot:

- Social worker and care coordinator

- Nutritionist/diabetes educator (part time)

- Psychiatric nurse practitioner

Salary paid through Blueprint for Health:

- Medical social worker

- Nurse care coordinator

Salary paid through capitation pilot and Blueprint for Health:

- Patient panel and referral managers

Thomas Chittenden Health Center has a cozy, welcoming atmosphere, with hardwood furnishings, rocking chairs, and photos of children adorning the walls. “A lot of patients see it as a cocoon,” says Haddock.

In 2018, the clinic hired Nina Gaby, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, to meet demand for behavioral health services; previously, clinicians struggled to find psychiatrists for patients. Having someone in house also helps convince those who may be reluctant to pursue psychiatric care. “They feel like they already know me because Joe Haddock has walked them over and introduced me,” Gaby says. “That really improves compliance.” She has been surprised by the acuity and range of patients’ behavioral health needs. Gaby also has worked with several “independent Vermont men who have never ever talked about any of the things that have gone on in their lives.”

Having Anderson, Gaby, and other team members enables Chittenden to surround vulnerable patients with supportive services. When an 18-year-old patient became pregnant, Haddock knew she and her baby were at risk. She was overweight and had had a troubled childhood. Haddock tapped several colleagues: Mary Anne Kyburz-Ladue, the nutritionist and diabetes educator, offered advice to the young woman when she developed gestational diabetes; Anderson helped her apply for supplemental nutritional benefits and called to check on her every week; Liz Moss, a medical social worker, offered counseling and, eventually, referred her to Gaby, who diagnosed and began treating her for depression.

By the time Haddock and Gaby met the baby — who weighed less than five pounds at birth — the new mother had gained a sense of confidence in her role. “She’s looking at the baby, this little tiny thing, and she said, ‘I never thought I would ever be able to produce something so beautiful,’” Gaby says. “So the bonding has happened. I think in order to bond, people need to feel they are safe.”

Panel Management and Performance Improvement

Thomas Chittenden Health Center has leveraged its electronic health record (EHR) system to flag patients with chronic conditions whose disease is out of control, identify those who need preventive care, and generate automated calls or messages to patients. From 2016 to 2019, the number of hypertensive patients with their blood pressure under control rose from 54 percent to 59 percent and the number of patients with diabetes under control went from 85 percent to 89 percent.

Rick Dooley, a physician assistant, used the system to increase the number of adolescent patients who receive the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Notices are automatically sent to families with teen children who were overdue for annual wellness visits and nurses receive electronic reminders to ask about HPV vaccination status at each adolescent well visit. Dooley also published monthly reports on each prescriber’s HPV vaccination rates and quarterly reports comparing the clinic’s HPV rate to the state average.

Dooley also has leveraged the EHR system to track and reduce potentially unnecessary opioid prescribing. He’s convened clinicians each month to review their prescribing patterns and invited University of Vermont pain management specialists to offer advice on best practices. From 2018 to 2019, this resulted in a 22 percent reduction in opiate morphine milligram equivalent prescribing.

Wright & Associates Family Healthcare

In neighboring New Hampshire, Wright & Associates Family Healthcare was founded by two sisters: Wendy Wright, a nurse practitioner, and Becky Manter, the practice manager. The sisters opened their first clinic in Amherst, N.H., in 2007 and the second in 2011 in Concord, the state capital, where they recognized a need in the market. “There was just one primary care provider in Concord taking new patients,” says Wright. “You would put your name on a list and, as patients left, they would enroll a new patient.”

Wright & Associates’ Concord practice is part of an increasing number of nurse practitioner–led clinics that are filling gaps in access to primary care. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia allow nurse practitioners to care for their own patient panels and work independently of physicians. While the supply of primary care physicians increased only nominally from 2010 to 2016, the number of primary care nurse practitioners doubled. Compared with physicians, nurse practitioners are more likely to practice in rural and low-income areas and to serve Medicaid beneficiaries.3 A recent study found that, compared with patients treated by physicians, patients treated by nurse practitioners incurred fewer hospitalizations, including for conditions that may be treatable in ambulatory care settings.4

Word of the Concord clinic spread, attracting patients from up to an hour away. Today three nurse practitioners serve about 2,500 patients; the small panel size enables nurse practitioners to hold much longer appointments than are typical in primary care. Some patients are homeless or struggle with substance abuse. (The clinic is located next to a soup kitchen and homeless shelter.) Others are recent immigrants who work in the region’s manufacturing plants or young people drawn to the area’s relatively low cost of living. About a third of patients are covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or Tricare (for active and retired members of the military), and most of the remainder by private insurance. Wright and Manter consider many of their privately covered patients to be underinsured because they face very high copayments and deductibles.

During the pandemic, the Concord practice has remained a lifeline to residents as other local primary care practices closed their doors. It has remained open for in-person visits, including curbside COVID-19 testing, as well as virtual visits seven days a week. With patient volumes plummeting 60 percent in the spring, leaders had to furlough three nurse practitioners and four medical assistants across the two sites. By summer, they were able to rehire all but one staff member as volumes rebounded. The practice has been sustained by a $300,000 forgivable loan from the Paycheck Protection Program as well as $7,000 from the CARES Act to purchase protective equipment.

Wright & Associates Family Healthcare’s Concord office is sandwiched between a soup kitchen, homeless shelter, and the public defenders’ office. It’s down the street from the state capitol building.

Lean Staffing, Long Visits

To limit operating costs, the Concord clinic is minimally staffed and shares office space with unaffiliated providers, including a lab testing service. Each of the three nurse practitioners partners with a medical assistant, who queues up tasks before office visits, follows up on tests and referrals, and works with other medical assistants to handle billing and scheduling and field patients’ calls.

Only 10 to 12 appointments are scheduled for each nurse practitioner a day, giving them a full hour to devote to new patients, 45 minutes for well-child visits or visits following surgeries or hospitalizations, and 30 minutes for other follow-up appointments. By contrast, the average primary care visit lasts 20 minutes.5 Wright says the longer visits enable nurse practitioners to offer comprehensive preventive and problem-based treatment; this approach is not only consistent with nurse practitioners’ training in holistic health but also serves patients’ interests, since most have more than one condition or concern. The additional time also enables clinicians to build rapport with patients. “We hear from patients, ‘I’ve never spent so much time with a clinician before. You actually listen to me,’” says Manter. “And that’s the biggest thing.”

Integrating Behavioral Health Services After Struggling to Find Psychiatrists

In 2017, Concord began screening all patients for depression and substance abuse and uncovered a startlingly high degree of need. About 40 percent of patients are diagnosed with some type of behavioral health problem, mostly commonly depression, anxiety, and/or substance use disorder, often related to past instances of sexual abuse or other trauma. Nurse practitioners are typically able to refer patients to counselors, but they struggle to find psychiatric providers for patients requiring medication management. In recent months, staff have seen even more patients struggling with anxiety and depression. “Visits were long and hard before the pandemic; they’re longer and harder now,” says Wright, noting that patients have been returning to the office “mentally and physically exhausted.”

Thanks to a statewide settlement agreement, the clinic now has access to emergency psychiatric services for patients who appear to be suicidal, delusional, or otherwise in crisis. Over the past year, the mobile crisis team came to the clinic five times to perform an immediate evaluation and transfer.

Concord clinicians also have helped people coping with addiction, mainly opioid use disorder, treating some 360 patients since 2011 with antagonist medications that block the effects of opioids. Nurse practitioners do not offer treatment with buprenorphine, an agonist medication commonly used in treating opioid use disorder, because prescribing it requires a waiver process that is too time-consuming and expensive, says Manter. Many patients with opioid use disorder find their way to Concord because the clinic partners with residential drug treatment facilities. Before discharging patients, staff from the facilities bring patients to the clinic for a “warm handoff” to a nurse practitioner. The clinic guarantees they’ll see these patients within seven days of their discharge.

About a third of clinic patients with opioid use disorder recover, but many others end up in prison or stop turning up for treatment for other reasons. “It’s heartbreaking,” Wright says. “In the short time we have them, we try to address some of their primary care needs. Because, unfortunately, when we get them, 50 percent are hepatitis C positive and about 10 percent are HIV positive. So that is the alarming part.”

Wright & Associates Family Healthcare was founded by two sisters, Wendy Wright, N.P. (left), and Becky Manter, practice manager (right).

Leveraging Value-Based Payments to Enhance Care

In 2012, Wright & Associates’ Amherst and Concord practices joined with New Hampshire’s 10 other nurse practitioner–led practices to form the nation’s first nurse practitioner ACO under a contract with Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield.6 (At the time, Medicare only accepted practices led by physicians into its Shared Savings Program for ACOs.) The 11 practices pooled their patients into one risk pool to test whether they could succeed under value-based payment. Under the contract, each of the practices received per member per month fees — from $3 to $7, depending on patients’ acuity, in addition to fee-for-service payments — to coordinate and oversee care for Anthem patients, including those with marketplace coverage and Medicaid managed care beneficiaries. The practices were eligible to share in any savings from better coordinating patients’ care if they met benchmark performance levels on measures of preventive care, chronic care management, and cost control.

Overall, the nurse practitioner practices met quality thresholds over three years of the program and their patients cost $66.85 less per member per month than did physician-managed patients in another Anthem risk pool, mainly because of lower hospitalization rates. Unlike most other private insurers, Anthem pays nurse practitioners on par with physicians, so the lower reimbursements did not account for the nurse practitioner practices’ lower costs.

The data also showed that New Hampshire’s nurse practitioners were caring for very sick patients, including those with multiple chronic conditions (such as cancer, coronary artery disease, diabetes, and kidney disease). “There’s a misperception that nurse practitioners are mostly taking care of younger, healthier patients and handling straightforward things,” says Wright. “This work showed that’s just not true.”

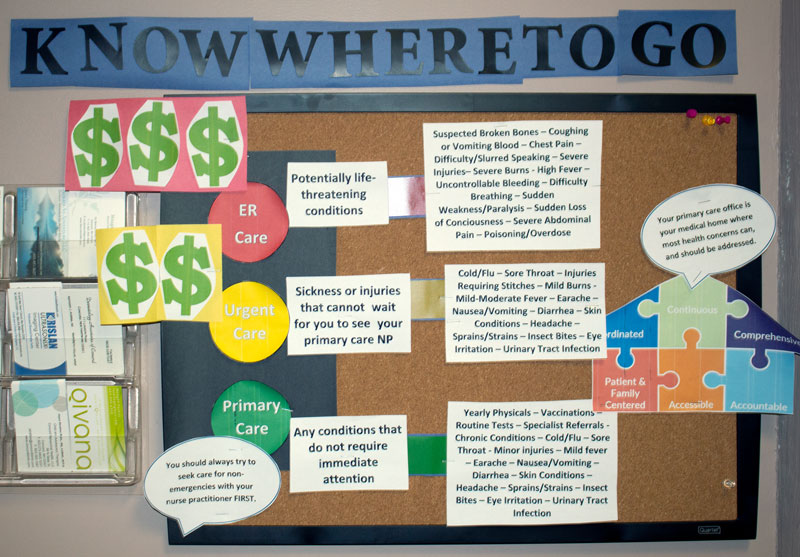

For the past two years, the Concord clinic has had a separate ACO contract with Anthem (rather than pooling patients with other nurse practitioners-led clinics). In 2019, the clinic exceeded the average performance rate among primary care practices statewide on several measures of appropriate preventive care and chronic disease management. Clinic patients also had fewer hospitalizations than the statewide average, though they had higher-than-average rates of avoidable ED visits, which leaders attribute to ingrained behaviors related to the region’s primary care shortages. “Going to the ED is all the patients have known,” says Manter.

To help change behavior, the clinic launched a campaign to educate patients about the circumstances under which they should seek emergency, urgent, or primary care — emphasizing the concept of a primary care medical home that can address most health concerns. Along with posting educational signs in the office and holding regular conversations with patients, the clinic sends letters to patients who’ve visited the ED for a condition that could have been managed in primary care. The letters note that ED visits could wind up costing patients more out of pocket than office visits.

Concord has earned modest shared savings from its participation in ACO contracts — about $35,000 in the first year, $20,000 in the second, and $6,000 in the third — which has enabled leaders to hire another medical assistant.

Concord clinicians partnered with a Doctor of Nursing Practice student to develop a campaign to educate patients about when to seek primary, urgent, or emergency care.

Shared Approaches

Vermont’s Thomas Chittenden Health Center is much larger than Wright & Associates’ Concord clinic and has more supportive state policies to lean on. Still, leaders at both practices face similar challenges, including engaging patients in care, recruiting clinicians, and financially sustaining their practices. Below, we outline some of the strategies they’ve developed to address these challenges and develop care models that benefit the low-income patients they serve.

Building trusting, long-term relationships

People have many reasons for not seeking primary care. Some are practical: They can’t miss work or find childcare, or they’re worried about costs. Others have personal reasons: They don’t trust the health care system, they had a bad experience with a doctor, or they don’t want to be told they should stop smoking or lose weight. Fears surrounding the coronavirus also have hindered many from seeking routine services, such as vaccinations or cancer screenings, or from reaching out when they feel unwell.

One way the independent primary care clinicians profiled here encourage people to pursue care is by forging personal connections, which they say are key to earning a patient’s trust and promoting healing. For instance, when a Wright & Associates’ patient repeatedly turned up at the ED after her husband died — apparently looking for company — a medical assistant helped her get a service dog and scheduled an office visit for her every month until she felt less lonely. At Chittenden, both clinicians and care coordinators visit patients in their homes, particularly when they haven’t turned up for appointments, and seek to build trust in the practice — something Haddock refers to as “institutional bonding.”

Still, it is often hard for these clinicians to engage patients. The Wright & Associates’ Concord practice is open from 7:00 a.m. until 5:30 p.m. on weekdays and Saturdays. But every day, a handful of patients fails to turn up for scheduled appointments, although a new texting system has begun to reduce that number. Staff at Chittenden say it can be hard to convince stoic Vermonters to accept help, particularly for social services like Meals on Wheels when they can no longer cook for themselves. “I play guitar at funerals, and I always play the song ‘Amazing Grace,’” Haddock says. “I tell patients it takes amazing grace to accept help. Most of them, they’ll buy that.”

Attending to affordability concerns

Acknowledging patients’ concerns about the affordability of care and taking steps to minimize their out-of-pocket costs are other engagement strategies. At a time when patients are shouldering more of the costs of care, only a minority of physicians say they’ve broached the subject of treatment affordability with patients.7

Wright & Associates’ Concord practice follows a “no surprises” policy: Staff check people’s insurance before visits and let patients know precisely what services will cost them. The clinic also has secured agreements with a local hospital and lab so their patients can get discounted tests or imaging services. Concord’s leaders say their treatment approach — doing as much as possible in one visit — respects patients’ time and means they don’t have to pay additional copayments for follow-up visits. The clinic also offers patients the option to pay off their services via installment plans.

Both organizations profiled in this case study say that patients requiring medications, lab tests, and other services to manage chronic conditions often face cost barriers because their plans require high deductibles and copayments. Clinicians report that many patients can’t afford prescription drugs, particularly medications needed to manage chronic conditions. Kyburz-Ladue, Chittenden’s nutritionist and diabetes educator, says it’s not unusual for a patient with diabetes to stop taking insulin because of costs. Staff at both clinics help enroll eligible patients in pharmacy assistance programs and look for alternatives to expensive drugs, but costs remain a major barrier. Nationally, one of five adults under age 65 hasn’t filled a prescription because they can’t afford it.8

Helping patients find social supports

New England poverty can be obscured by its charming towns and mountainous landscapes, but clinicians in both Vermont and New Hampshire report that some of their patients are living hand to mouth. “Nurse practitioners who make home visits say the house is in squalor, that it is freezing, that they are living on minimal amounts of food,” Wright says. Thomas Chittenden Health Center has a full-time social worker to connect patients with social supports, and the community is generous with resources like subsidies for fresh food and volunteers who visit older adults. Still, there’s an acute lack of affordable housing. “There are years-long waits for subsidized housing,” says Anderson, a social worker and care coordinator. “I go through Craigslist with people trying to find the cheapest apartments. In the summertime, people who are homeless live in the woods.”

Clinicians at Wright & Associates’ Concord practice also point to a lack of affordable housing, along with a lack of public transportation and services in rural areas. Medical assistants help patients sign up for Medicaid, discounted utility programs, or other benefits. But with fewer supportive programs in New Hampshire than in neighboring states, there are limits to what they can do.

Everything comes back to primary care. A patient who had been started on opioids in the ED was told, ‘Contact your primary care provider to manage your pain.’ We sent a patient to a behavioral specialist, a nurse practitioner who can prescribe, and she said, ‘I no longer prescribe any of those. Go back to your PCP.’ It all comes back to us, and that’s so, so hard.

Growing a pipeline to cope with primary care workforce shortages

Both primary care practices struggle to recruit and retain clinical staff. Unlike some competing academic medical centers, community health centers, or health care organizations in health professional shortage areas, the clinics can’t offer loan repayment or forgiveness programs as recruiting enticements. And leaders say many clinicians aren’t comfortable working as autonomously as is required in independent practice, and they may be lured by higher pay offered elsewhere.

To cope, both practices have tried to build their own pipelines.

Leaders at Wright & Associates’ Concord practice invest significant time in developing staff members’ skills and helping them feel comfortable working independently. For their first six months, newly hired nurse practitioners work at a significantly reduced schedule and Wright reviews and offers feedback on their patients’ charts. In addition, one of the clinic’s medical assistants, who recently earned a nursing degree, will help triage patient calls and has begun offering diabetes management classes. Recently, the clinics received federal grants to support its nurse practitioner mentorship and residency programs.

Chittenden is paying for one of its nurse practitioners to receive a psychiatric certification to help meet demand. But Wright & Associates’ Concord practice has not been able to recruit a psychiatric provider and struggles to find places to refer patients needing psychiatric care. Nationally, more than half of U.S. counties lack a psychiatrist and fewer than half (43%) of practicing psychiatrists accept Medicaid.9

Leveraging delivery and payment reforms

Thomas Chittenden Health Center’s success to date under a capitation pilot suggests it may be able to succeed were such a payment approach extended for all its patients. But capitation could prove harder for smaller independent practices or those that don’t have the external supports that Vermont’s primary care clinicians receive.

By joining with other independent practices, Wright & Associates’ Concord practice has been able to participate in ACO contracts. While modest, the incentive payments have enabled leaders to hire an additional medical assistant to help close gaps in preventive care or chronic disease management. “It completely changed our work,” says Manter.

But Concord has struggled to develop other value-based contracts with Medicare, Medicaid managed care plans, or private payers, which Wright attributes to the fact that the practice is too small to get much notice from payers. Even though nurse practitioners generally earn less than primary care physicians, most payers have not recognized their work or rewarded their cost effectiveness, Wright says. “We’ve tried to negotiate as a group, but we just can’t get a foot in the door.”

While larger health care institutions can spread out their financial risk by cross-subsidizing one service line with another, independent primary care practices do not have that ability. Even though they operate as small businesses, they must juggle different types of payment from different payers, and some payments arrive unpredictably and long after a service is delivered. “We’re making it,” says Wright. “My bills are paid, and I have no debt. But I take a paycheck only 50 percent of the time.”

Starting in 2021, smaller and independent primary care practices in some regions will have the option of joining the new federal Primary Care First program, under which they will receive capitated payments for each patient covered by Medicare as well as $50 fees for office visits. Practices also can earn incentives for achieving performance targets tied initially to reduced hospitalizations. Some practices serving particularly complex patients may earn higher per member per month fees, but one estimate finds that this approach will not represent an increase in revenue for most practices. In addition, unlike the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus multipayer initiative, which also seeks to strengthen primary care, Medicaid and private payers are encouraged but not required to follow this approach.

During the pandemic, public and private payers began offering providers equivalent reimbursement for virtual and office visits. To ensure telehealth is a viable option for primary care practices longer term, these policies will need to be continued, primary care leaders say. “Telehealth needs to remain an option,” says Wright. “Some people are still too scared and won’t come in.” In one recent case, a Wright & Associates’ nurse practitioner used a virtual visit to help a husband perform an abdominal exam on his wife to diagnose appendicitis.

Looking Ahead

Advocates continue to argue that, to improve population health and reduce overall health care spending, much more money must flow into primary care. Some have argued for approaches that take into account and reward the value of trusting relationships. States, including Rhode Island, are explicitly mandating higher spending by Medicaid and private insurers on primary care, but average spending on primary care in the United States is still well below other industrialized nations.10 Such investment also must take into account the social and behavioral health needs of vulnerable patients who, as these profiles demonstrate, often require additional supports that test the capacity of practices to sustain themselves.

While committed to their patients and communities, clinicians at the Vermont and New Hampshire clinics agree that their work was hard to sustain, even before the pandemic: “The worst thing that could happen to primary care is if we didn’t change anything,” Haddock says.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following individuals who generously shared information and insights. Thomas Chittenden Health Center: Lisa Anderson, Rick Dooley, Nina Gaby, Joe Haddock, Mary Anne Kyburz-Ladue, Maggie Mangham, Cheryl McCaffrey, and Liz Moss. Wright and Associates Family Healthcare: Elizabeth Holt, Becky Manter, and Wendy Wright.

Commonwealth Fund case studies examine health care organizations that have achieved high performance in a particular area, have undertaken promising innovations, or exemplify attributes that can foster high performance. It is hoped that other institutions will be able to draw lessons from these cases to inform their own efforts to become high performers. Please note that descriptions of products and services are based on publicly available information or data provided by the featured case study institution(s) and should not be construed as endorsement by the Commonwealth Fund.