What is behavioral health?

Behavioral health refers generally to the promotion of mental well-being and the prevention and treatment of mental health and substance use concerns. An individual’s level of behavioral health can fall anywhere on the spectrum from illness to positive mental well-being, and it can vary over the course of a lifetime.

Behavioral health conditions arise from the interaction between genetic and environmental factors, and clinicians diagnose them based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the handbook used by health care professionals in the United States and much of the world. Examples of common problems include anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia.

Behavioral health conditions are highly prevalent at all ages in the United States. According to the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in the past year:

- 21 percent of U.S. adults had a mental health condition such as depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia.

- 17 percent of youth had a major depressive episode.

- 11 percent of adults and 3 percent of youth had alcohol use disorder.

- 7 percent of adults and 5 percent of youth had an illicit-drug-use disorder.

- Close to 6 percent experienced “serious interference with major life activities,” also referred to as serious mental illness.

Behavioral health is deeply connected to physical health outcomes, as well as to social and economic well-being. People with behavioral health conditions are at greater risk of developing chronic diseases such as heart disease or diabetes and more likely to have unstable employment, insecure housing, or involvement with the criminal justice system.

What does behavioral health care look like in the United States?

Historically, mental health and substance use treatment and services in the U.S. were developed locally, based on type and level of need in a community as well as the availability of resources. Local responses were unconnected to one another as well as separated from the general health care system.

Today there is greater integration, though fragmentation in services and programs remains a problem. Behavioral health care is also more standardized, but some local communities still maintain unique programs.

Core behavioral health services typically include a combination of:

- screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, or SBIRT, for substance use disorders

- psychotherapy

- prescribed medications and devices

- partial or complete inpatient stays or residential treatment

- case management and care coordination services

- outreach and engagement services for people disconnected from care

- skills development and assistance with employment, education, and housing

- peer support groups, one-on-one peer support services, and other social supports

- education, engagement, and services for family members or others important to recovery

- mobile crisis teams and other crisis response services.

The continuum of behavioral health care services involves a wide variety of specialty providers, including psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, counselors, social workers, and marriage and family therapists. As behavioral health becomes better integrated with other health care, primary care providers are also becoming part of the workforce — sometimes out of necessity, when other providers are unavailable.

Other important behavioral health providers are case managers, occupational therapists, peer support specialists, recovery coaches, child development specialists, and community health workers. Behavioral health services can be delivered in clinical settings as well as in schools and other settings. In addition, community-based organizations are a source of nonclinical supports, sometimes provided by individuals who have had behavioral health conditions themselves.

Is access to behavioral health providers a big problem?

Poor access to behavioral health services is a serious obstacle to treatment. In some areas of the U.S., services are simply not available or affordable to the people who need them. People also may be unaware of services that are available. Discrimination is a problem as well.

In 2020, less than half of adults and youth with mental health conditions and less than 10 percent with substance use disorders got treatment over the course of the year. As in other areas of health care, there are striking racial disparities in access to behavioral health care. While access to services has improved steadily for white people over the past decade, there has often been less improvement in access for people of color, further widening racial disparities.

Provider shortages are a major reason that access to treatment is limited, particularly in rural areas. It’s estimated that the U.S. needs an additional 7,400 mental health providers to meet current demand. Substance use treatment is in especially short supply: wait times for certain services can be weeks or months, especially for children on Medicaid. People in urgent need of help with behavioral health issues sometimes spend hours, even days, waiting in the emergency department.

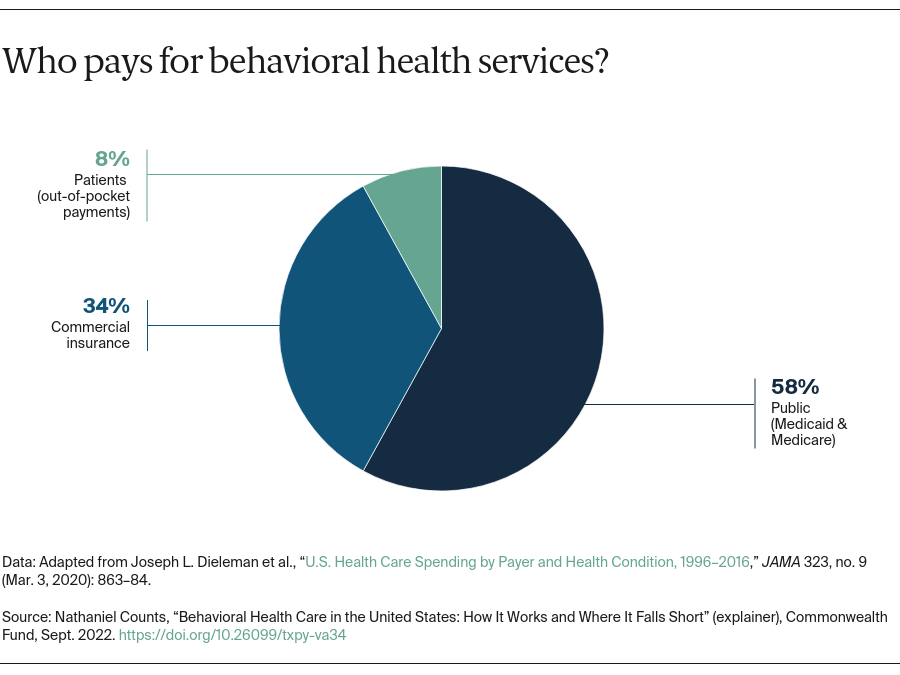

How is behavioral health care paid for?

In 2016, spending in the U.S. on behavioral health care was almost $180 billion. More than half of all mental health spending and nearly three-quarters of substance use treatment funding come from public payers such as Medicare and Medicaid. Behavioral health spending accounted for nearly 6 percent of all health care spending, an amount that includes only direct spending and not the substantial spillover on other health care costs — for example, those associated with comorbidities exacerbated by mental health or substance use problems.