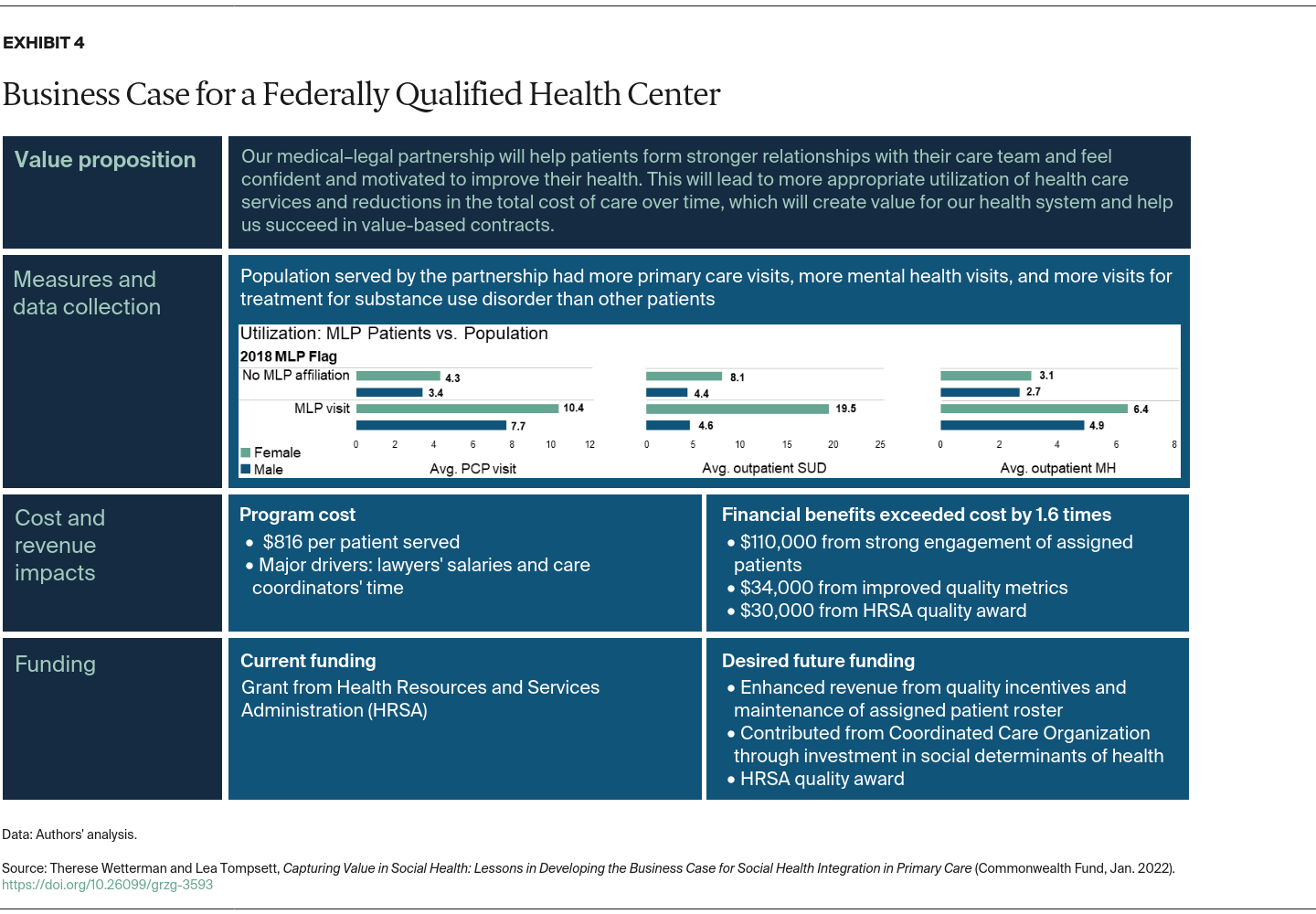

Understanding the costs also led teams to identify opportunities to operate more efficiently by redirecting resources. For example, one team found that attempting to connect patients with housing was extremely time-intensive and had a very low success rate, compared with connecting patients with assistance in paying utility bills, which was straightforward and had an immediate impact on health. Moreover, many patients screened positive for this specific need.

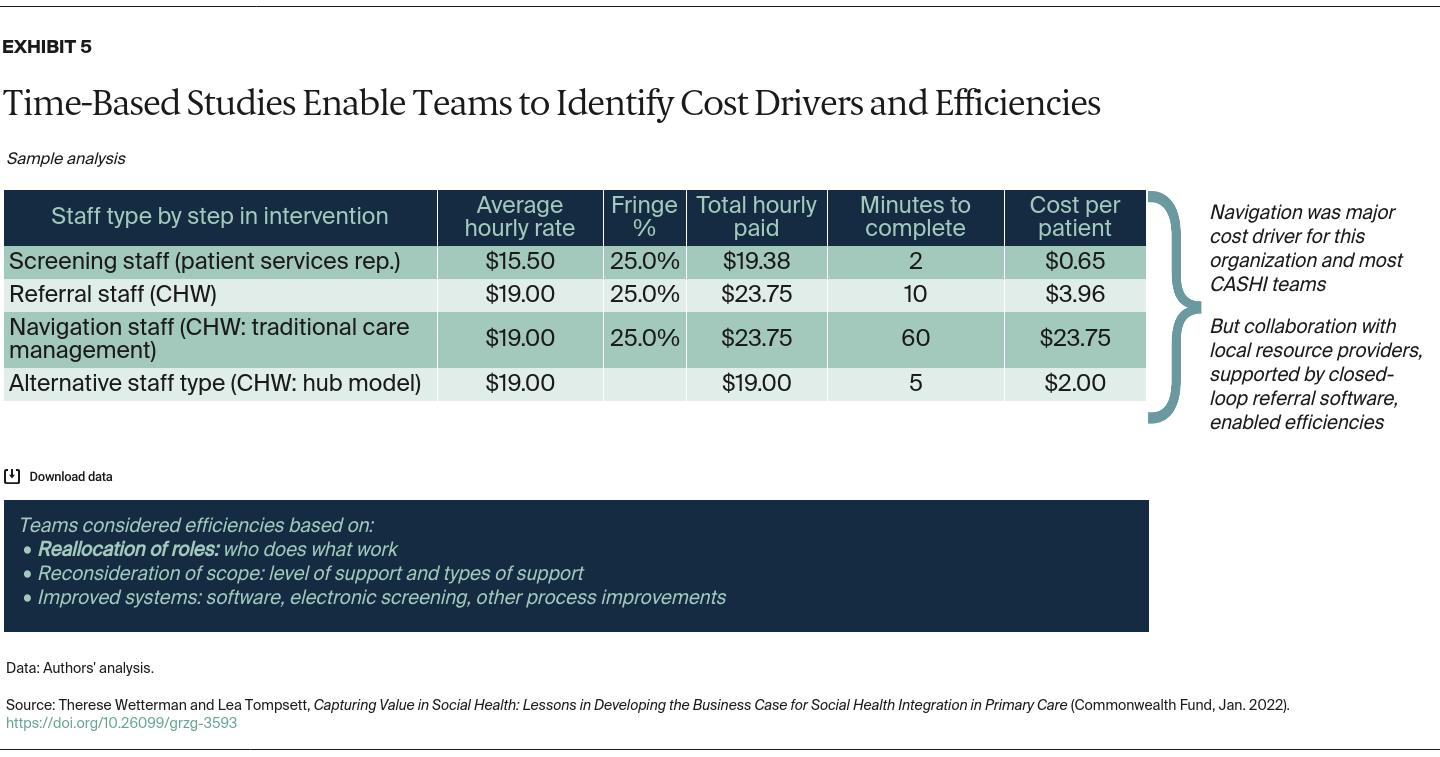

Teams also considered how to redistribute activities across team members, including social workers, community health workers, navigators, and nurses. One team calculated the financial impact of efficiencies gained by having CHWs and navigators focus on patients’ essential resource needs while nurse care managers focus on clinical issues. This analysis supported a request to leaders to hire additional CHWs.

Analyzing the costs of different services enabled teams to make evidence-based cases. Not only could they discuss ways to deploy resources to have the greatest impact, but they also could forecast what it would take to spread their social interventions based on such factors as population size, health needs, and staff required.

Despite these benefits, many teams struggled to access cost data, especially when it came to allocation of fixed costs or overhead. Having more support from finance staff could help teams maximize their investments in social health interventions.

Discussion

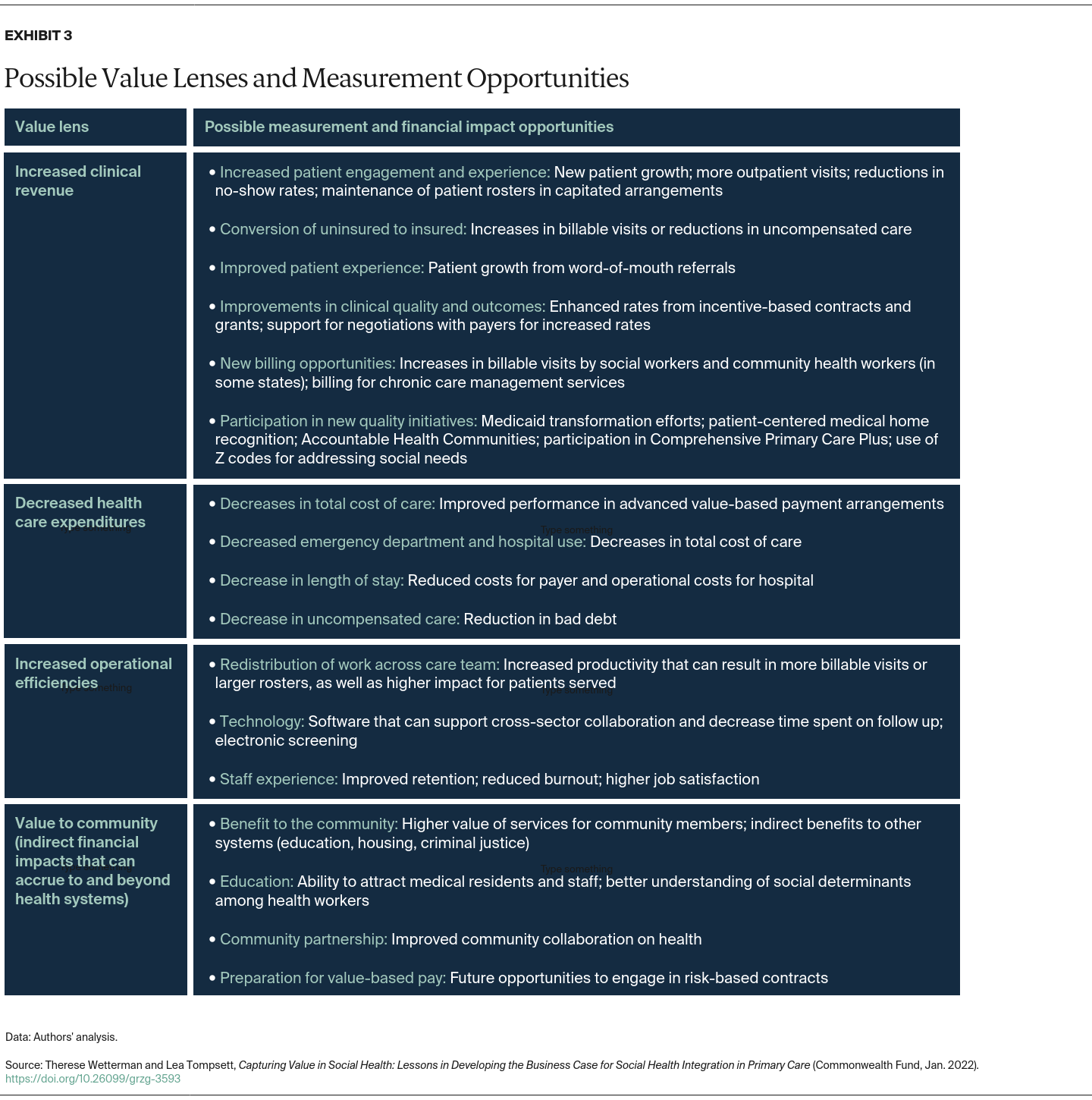

Many of the teams involved in the Collaborative to Advance Social Health Integration were early adopters of social health interventions, and decisions about whether to spread their social health interventions were not entirely dependent on demonstrating a clear ROI. However, identifying pathways and opportunities to sustainably integrate social health with their work and invest resources for the greatest impact was of deep interest to participants.

Through this work, it became clear that securing adequate reimbursement for navigation services to help patients access essential resources is critical. Social health workforces, including CHWs and navigators, are rarely able to bill for their services. This puts them in the position of being cost centers to their institutions instead of revenue generators, even though their work has value to their institutions, patients, and care teams.

To drive community health and equity, we believe the sector will need to move beyond a business case that quantifies the value of health care institutions’ efforts to address essential resource needs to one that quantifies the value of collaboration among health care organizations and their community partners. Applying our framework could shed light on the costs of services provided by each partner and the value they create. This, in turn, could inform the reallocation of resources to drive value at the community level. As one CASHI team found, effective use of closed-loop referral software across multiple community-based service providers yields insights into the amount and type of unmet essential resource needs within a community and the capacity available to address these needs.

Combining these data with rigorous cost and impact data among community partners has the potential to support more effective resource planning at the community level. However, this will require inclusion of community members in business case analyses to identify what it will cost to meet those needs and where targeted funding is most likely to support equitable health outcomes.

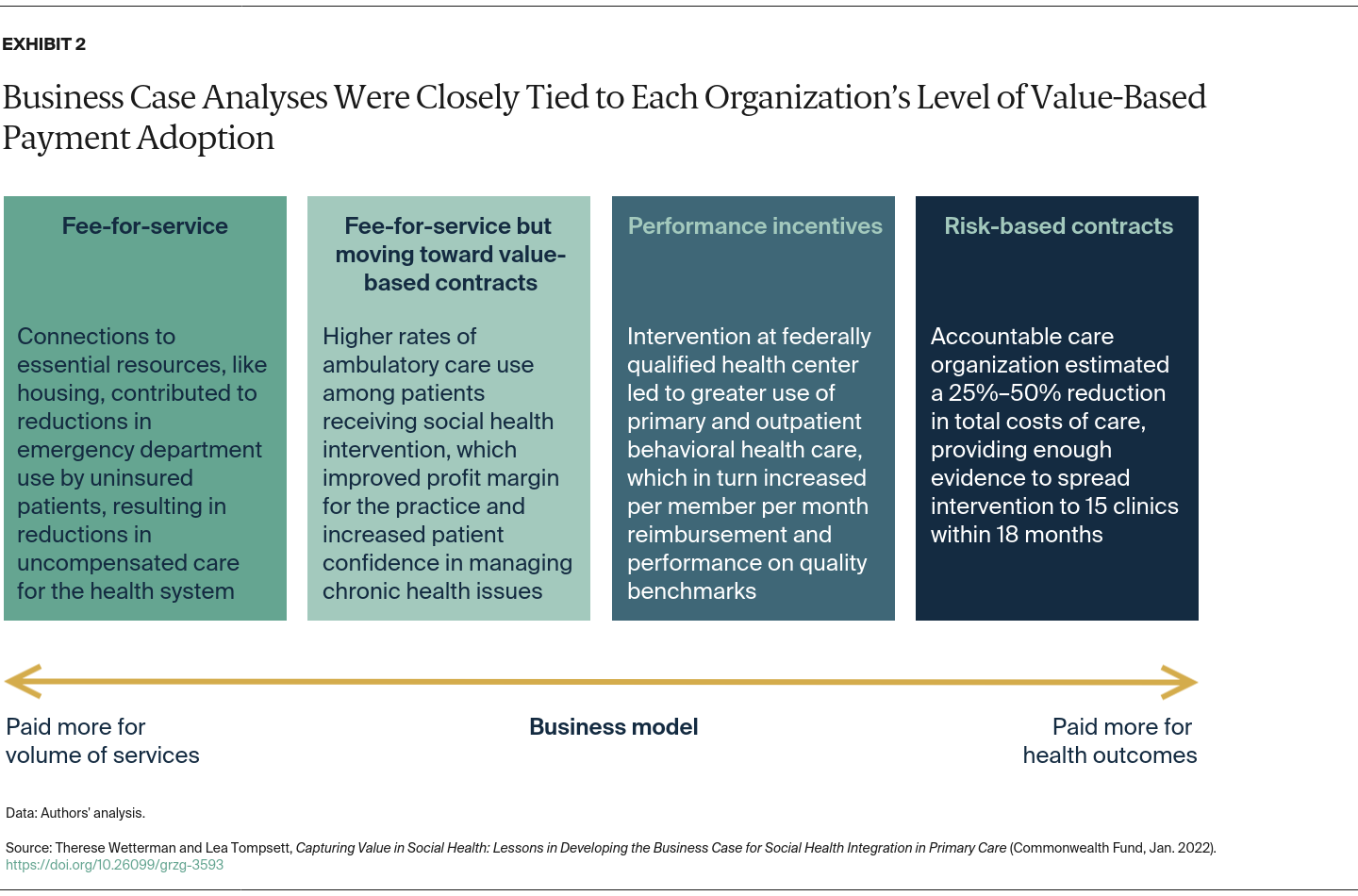

Finally, payment models that promote health care innovation and offer well-aligned incentives to drive health equity are needed.7 None of the CASHI teams were operating under payment contracts with explicit incentives to reduce racial and ethnic health inequities, despite the fact that estimates have placed the value of eliminating them at more than $200 billion.8 As such, efforts to understand the impacts of social health interventions across subpopulations, including patients of different race and ethnicity, were rare. More work needs to be done at the provider level to fine-tune data collection and analysis to identify inequities and understand how health care and other sectors can help eliminate them, including what the most suitable financing models are.