Abstract

- Issue: The Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) health insurance marketplaces provide a critical source of coverage and financial assistance. States operating their own marketplaces cover a significant number of consumers without access to employment-based health insurance or public programs. Federal actions under the Trump administration have undermined the marketplaces, but the new administration has opportunities to implement and advocate for policies that strengthen state-based marketplaces (SBMs) to ensure they continue to serve as a coverage safety net.

- Goal: Identify federal policies to support SBMs and the consumers they serve.

- Methods: Structured interviews with directors and officials from 17 SBMs and analysis of recent federal policies impacting SBMs.

- Key Findings and Conclusions: The Trump administration has hindered SBMs by establishing onerous requirements and creating consumer confusion. Affordability remains a primary barrier to marketplace coverage, and federal initiatives could help reduce premiums and cost sharing. SBMs are an important resource for people who do not have access to affordable insurance through their jobs, but federal policy changes are needed to clear an easier pathway to coverage. In addition, the federal government should reinvest in advertising and outreach for the federally facilitated marketplace.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed and exacerbated gaps in the health insurance landscape. During a time of economic upheaval, millions have lost access to coverage due to unemployment, reduced hours and income, and other challenges.1 The health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have served as a safety net by providing coverage options and financial assistance to the uninsured and those who have lost employment-based health insurance.2

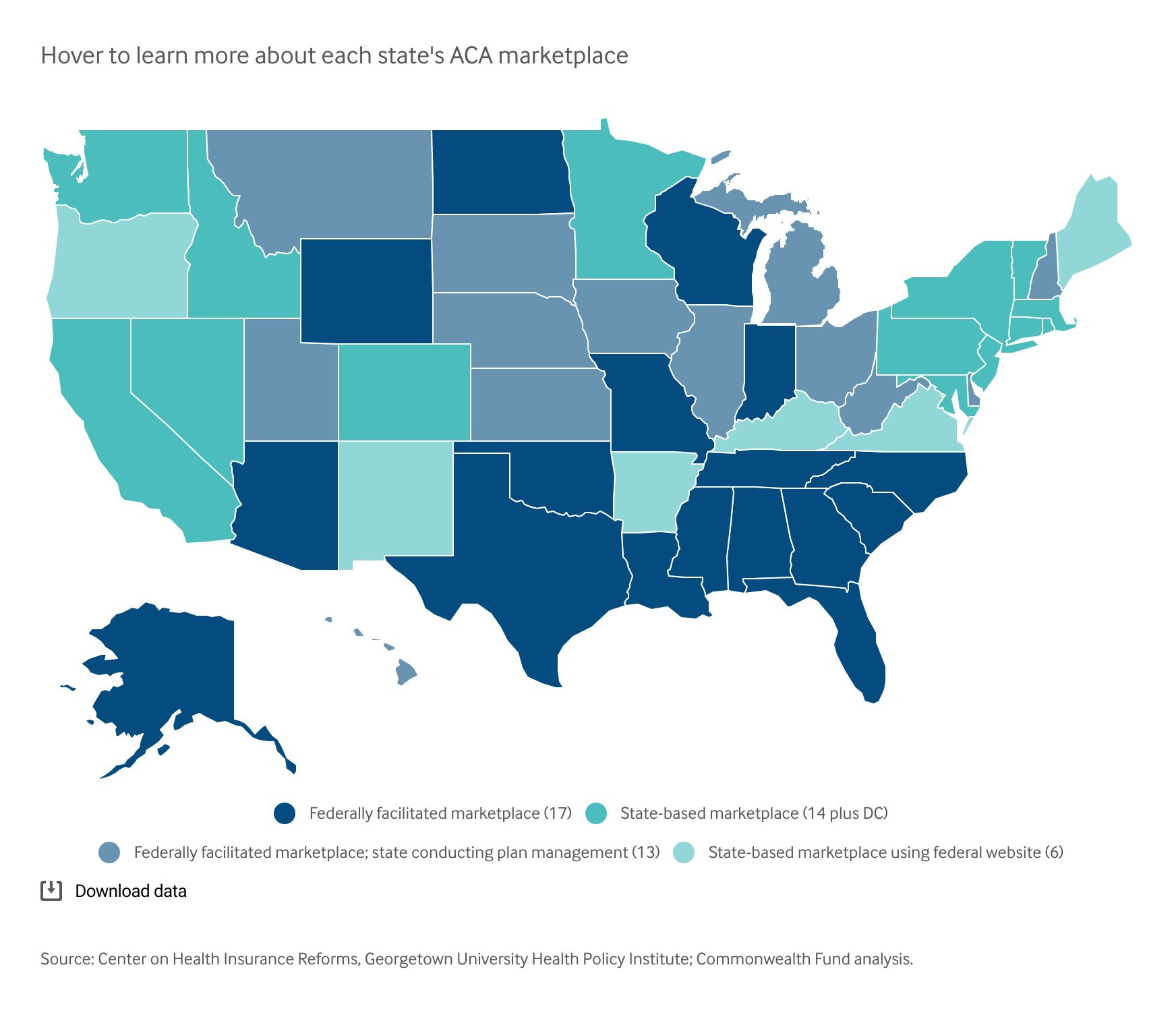

The ACA’s marketplaces are intended to make it easier for people to shop for and enroll in comprehensive coverage.3 Twenty states and the District of Columbia operate state-based marketplaces (SBMs), with six of these states relying on the federal marketplace website, HealthCare.gov, as an online platform for eligibility determinations, plan comparison, and other enrollment procedures. Thirty states use the federally facilitated marketplace.

The Affordable Care Act’s Health Insurance Marketplaces by Type

Nearly 4 million people were enrolled in SBMs in 2020.4 SBMs have a proven track record of investing in enrollment efforts, often achieving greater enrollment outcomes than the federally facilitated marketplace.5 They have also implemented policies that improve access to coverage and care, including opening more special enrollment periods and implementing standardized benefit designs to reduce consumer confusion and increase access to services.6

States operating their own marketplaces have significantly more autonomy than states on the federally facilitated marketplace, but SBMs are still impacted by federal policies. And while premiums, enrollment, and insurer participation in the individual market have stabilized in recent years, the Trump administration’s actions to undermine the ACA coincided with a rise in the uninsured and will likely have lasting impacts on both the insured rate and individual market premiums.7

To assess how federal policy decisions have affected SBMs and the consumers they serve, and how future federal actions could improve their operations and marketplace stability, we conducted structured interviews with directors and officials from 17 SBMs, including three SBMs using HealthCare.gov. This brief explores key themes from those interviews and identifies how federal policymakers can support the SBMs’ role as a source of comprehensive, affordable coverage.8

Key Findings

Federal Actions Have Hindered Marketplaces, Sowing Consumer Confusion and Doubt

Many SBM directors expressed that, since 2017, the federal government’s continuous attempts to obstruct or roll back provisions of the ACA have often impeded SBMs’ efforts to increase and sustain enrollment.9 Some officials lamented the time and resources spent responding to federal actions undermining the ACA. They identified numerous federally imposed obstacles, including the requirement for insurers to issue a separate bill for the portion of premiums covering abortion services (implementation of which has been blocked by the courts) and inconsistencies with how income is counted for purposes of Medicaid and marketplace subsidies.10

Officials described the frequent need to reassure people that the marketplaces remain a coverage option despite federal policies and rhetoric. As one director noted, “how much better off could we all be . . . if I didn’t have to spend money countering confusion and misinformation that is driven by federal rules and policies.”

Two recent federal policies were seen as particularly troublesome: the expansion of non-ACA-compliant insurance plans and the public charge rule.

Expansion of Non-ACA-Compliant Coverage Poses Problems for the Marketplaces

The Trump administration finalized rules expanding the availability of coverage that does not have to comply with the ACA’s individual market consumer protections. This coverage includes short-term, limited duration insurance as well as association health plans. The administration also proposed rules encouraging membership in health care sharing ministries — noninsurance arrangements that are largely unregulated by states or the federal government.11

Marketplace officials described how non-ACA-compliant plans negatively affect marketplace risk pools by siphoning away healthy people, who are attracted by the lower sticker prices and can pass health screenings that weed out people with preexisting conditions. Several directors noted that their states have limited the negative impact of certain products, particularly short-term, limited-duration insurance.12 Still, these officials remain concerned that non-ACA-compliant products are often deceptively marketed as cheaper alternatives to ACA-compliant plans, requiring SBMs to continually communicate the dangers of seeking off-marketplace coverage that can leave enrollees with significant medical bills if they seek care.

SBM officials called for federal action to reduce the presence of noncompliant products by reversing the Trump administration’s efforts to promote these arrangements. One director suggested a federal policy to crack down on companies using deceptive marketing tactics that misrepresent these products as comprehensive coverage.13 State insurance regulators have called for similar federal action.14

The Public Charge Rule Discourages Enrollment in Immigrant Communities

SBM directors also asserted that the Trump administration’s changes to public charge determinations have suppressed enrollment. Under a 2019 regulation — subject to ongoing litigation, as well as review by the Biden administration — the Trump administration added Medicaid to the list of publicly provided benefits considered in evaluating whether immigrants would be considered a “public charge” when seeking approval for permanent residency. This designation can prevent people with certain immigration statuses from becoming U.S. citizens. Under the new policy, the use of Medicaid, with some exceptions, can be considered in a public charge determination.15

While marketplace enrollees are not directly implicated by the new rules, most SBM officials reported that the regulation has had a chilling effect on marketplace enrollment. Directors described confusion over who the rule applies to, and how households that have members with different immigration statuses may forgo coverage entirely to protect a family member. Several officials noted that they have dedicated resources to combatting misinformation but face an uphill battle. As one director put it, “No matter how much money you invest in this, people are still afraid, so they’d rather take the risk of dying than the risk of not getting their citizenship.”

State-Based Marketplaces Eye New Federal Policies to Improve Affordability

SBM directors identified affordability as one of the biggest obstacles to obtaining health insurance, emphasizing high premiums and cost sharing as a key area for federal action.16 Officials noted that reducing cost burdens would help support SBMs in their mission to provide coverage as well as improve market stability by spurring robust enrollment and a broader, healthier risk pool. Directors highlighted two approaches: enhanced federal subsidies and federal reinsurance.

Enhanced Federal Subsidies Would Reduce Cost Barriers

While federal marketplace subsidies (along with some state programs) lower monthly costs and out-of-pocket expenses, SBM officials expressed that many people still struggle to afford the health insurance and care that they need.17