Introduction

Medicare beneficiaries have a strong preference for in-home care over institutions such as hospitals and nursing homes, a preference that has only grown during the COVID-19 pandemic. As well as allowing people who are older or have disabilities to be supported in a familiar and safe environment, in-home services are potentially less costly to Medicare than care delivered in inpatient hospital and other institutional settings.1

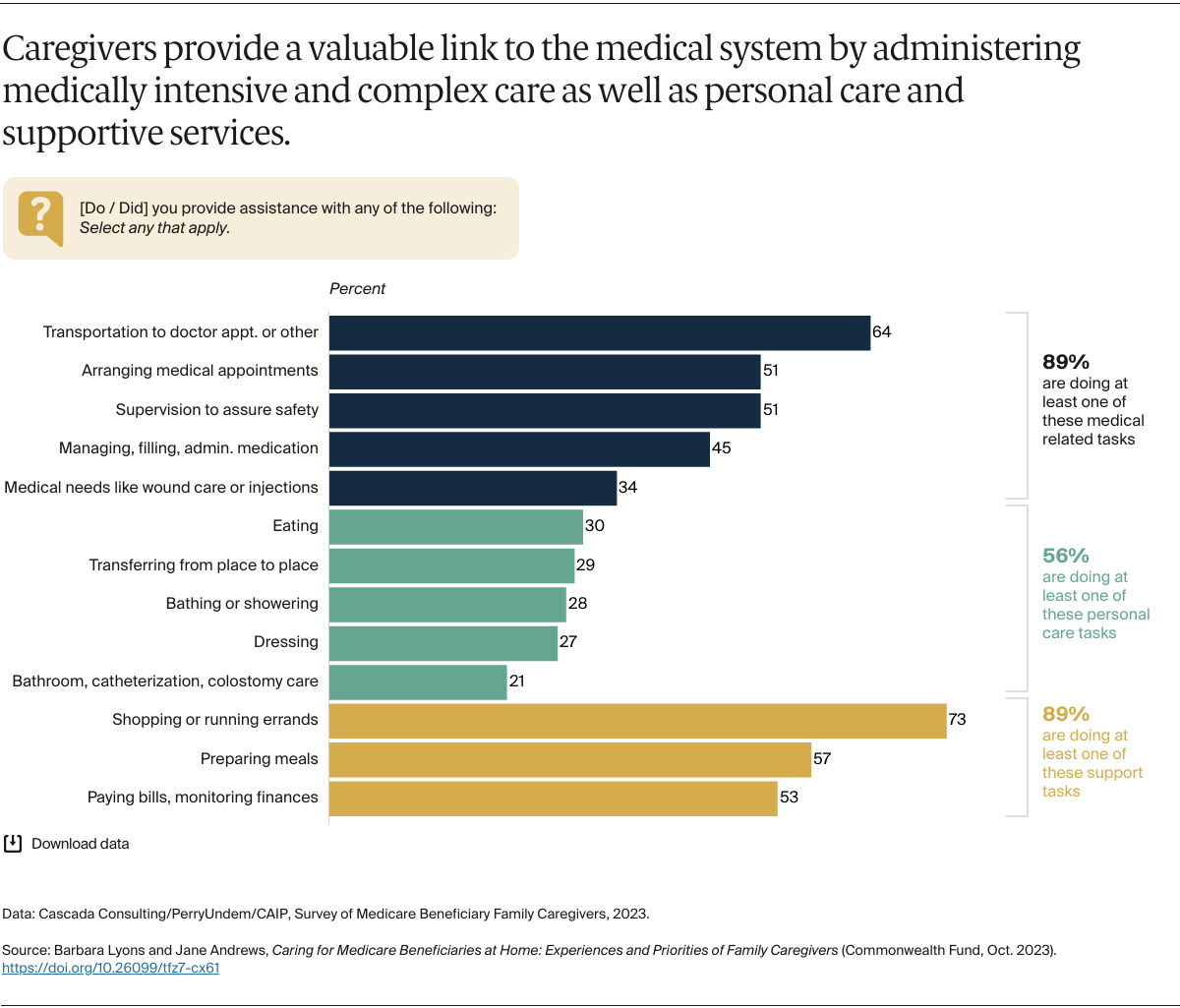

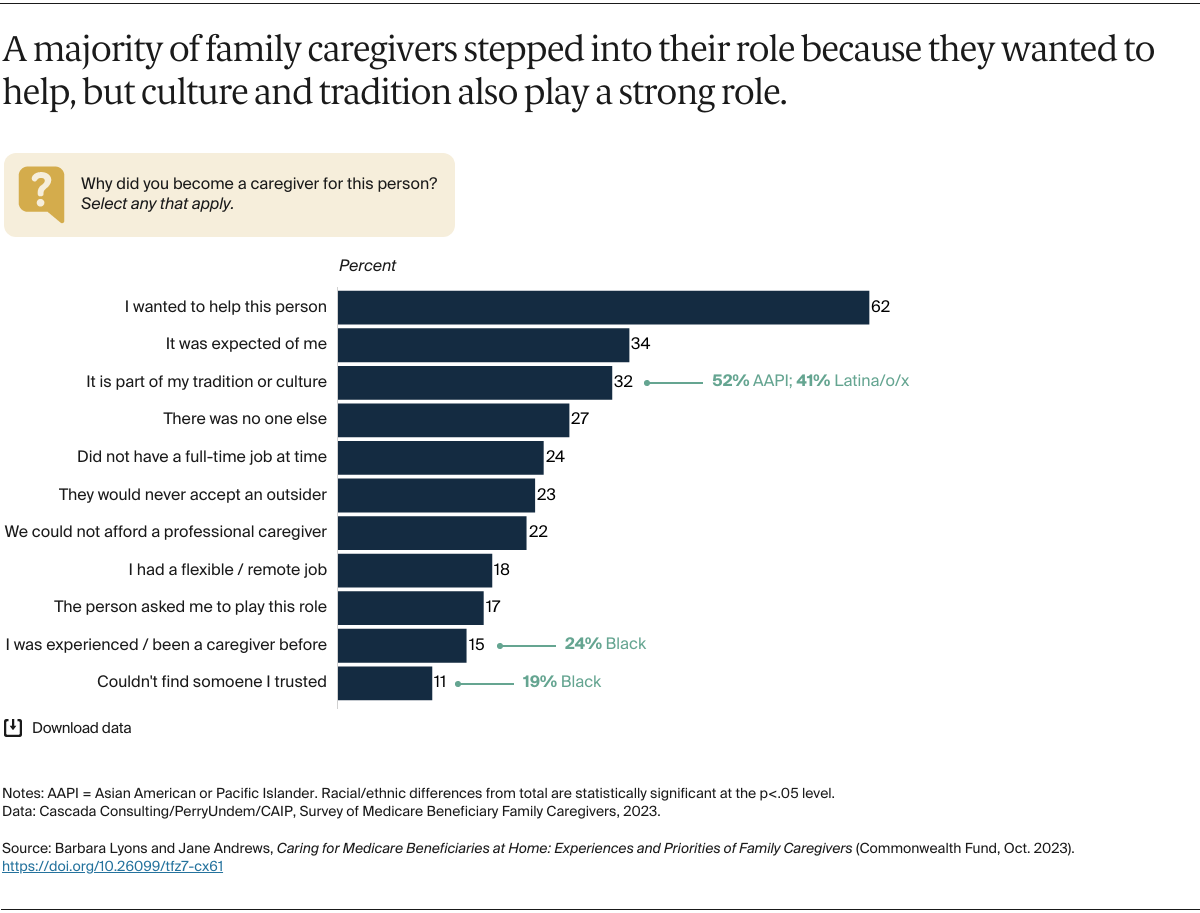

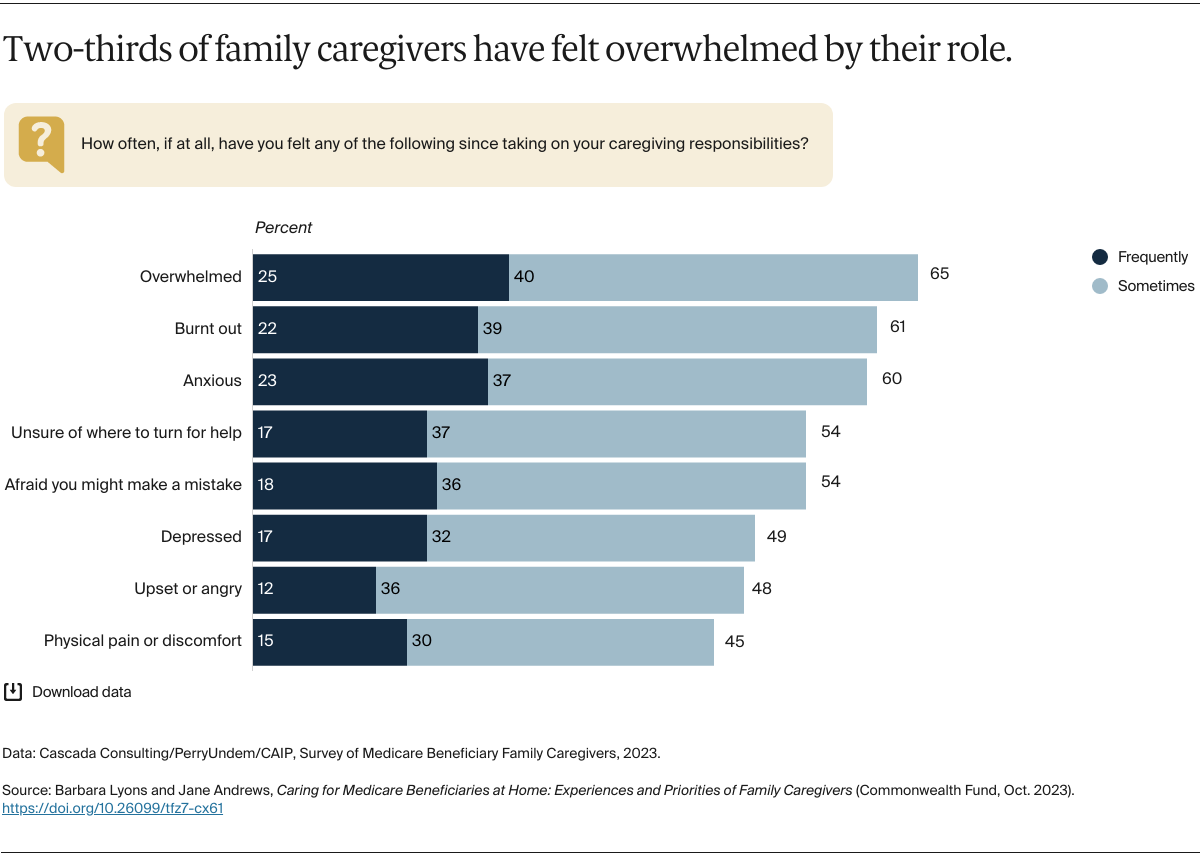

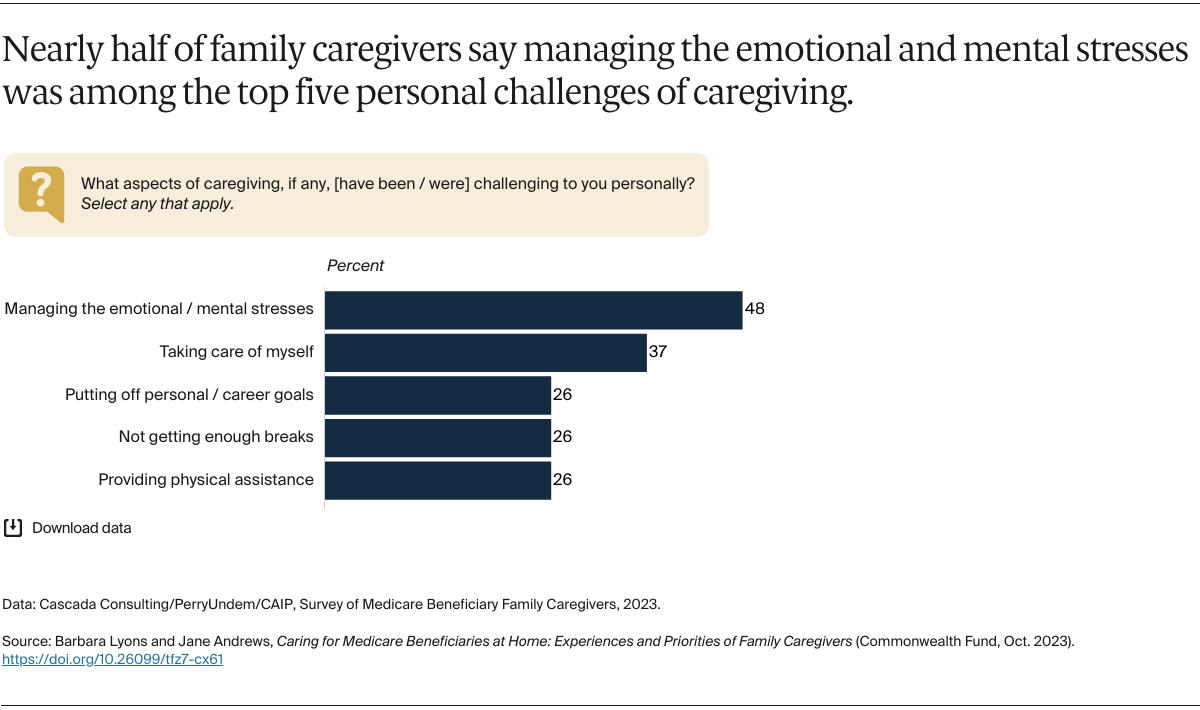

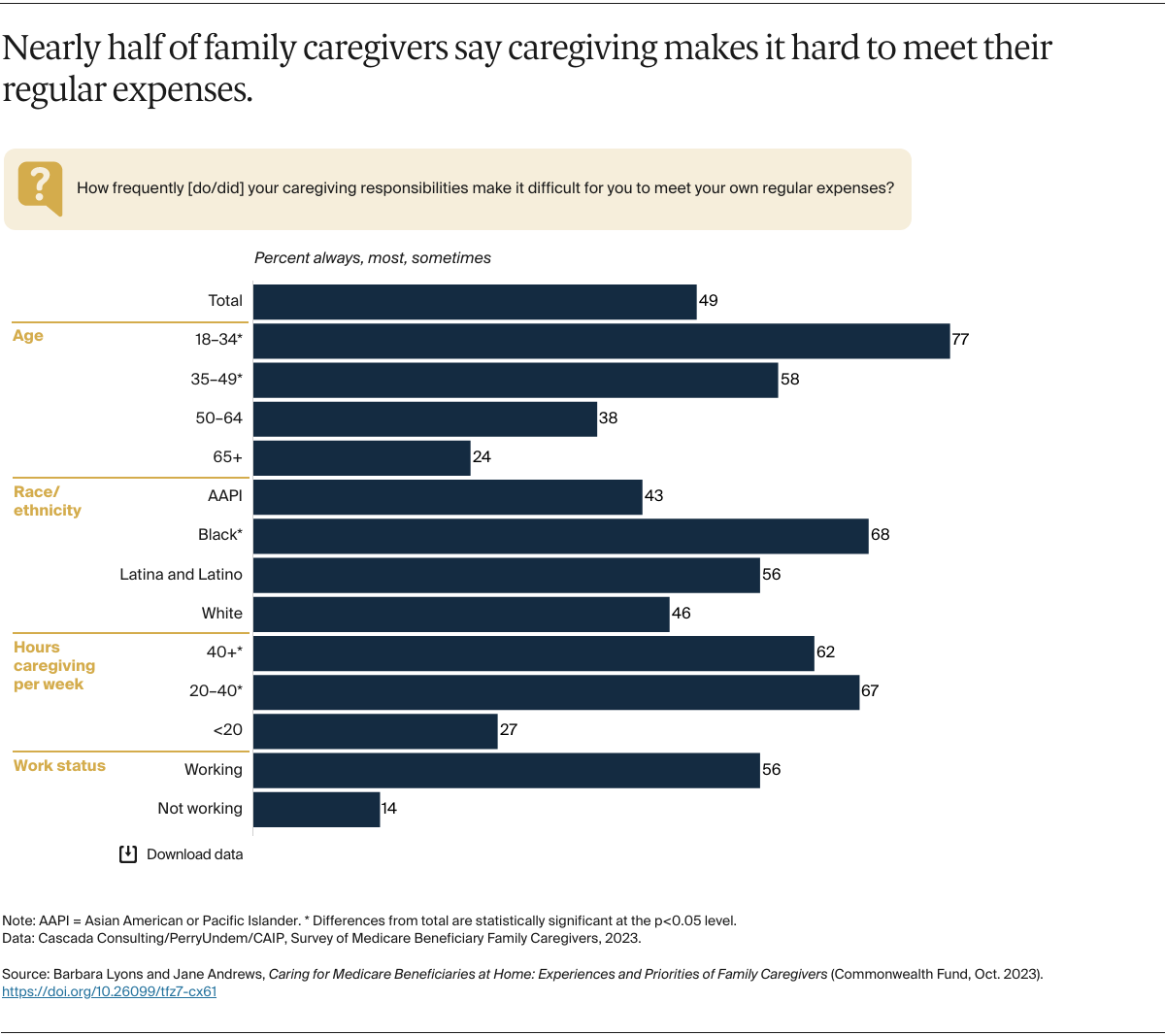

There are an estimated 42 million unpaid caregivers in the U.S. — disproportionately women — who provide care for someone age 50 or older.2 These caregivers are an essential component of the health care infrastructure as they provide at-home support for Medicare beneficiaries, often including intense and complex care. However, traditional Medicare does not cover many of the costs associated with care at home except under the limited home health benefit or under some limited Medicare Advantage supplemental benefit offerings. As a result, many family caregivers to Medicare beneficiaries provide care without payment, recognition, or respite.

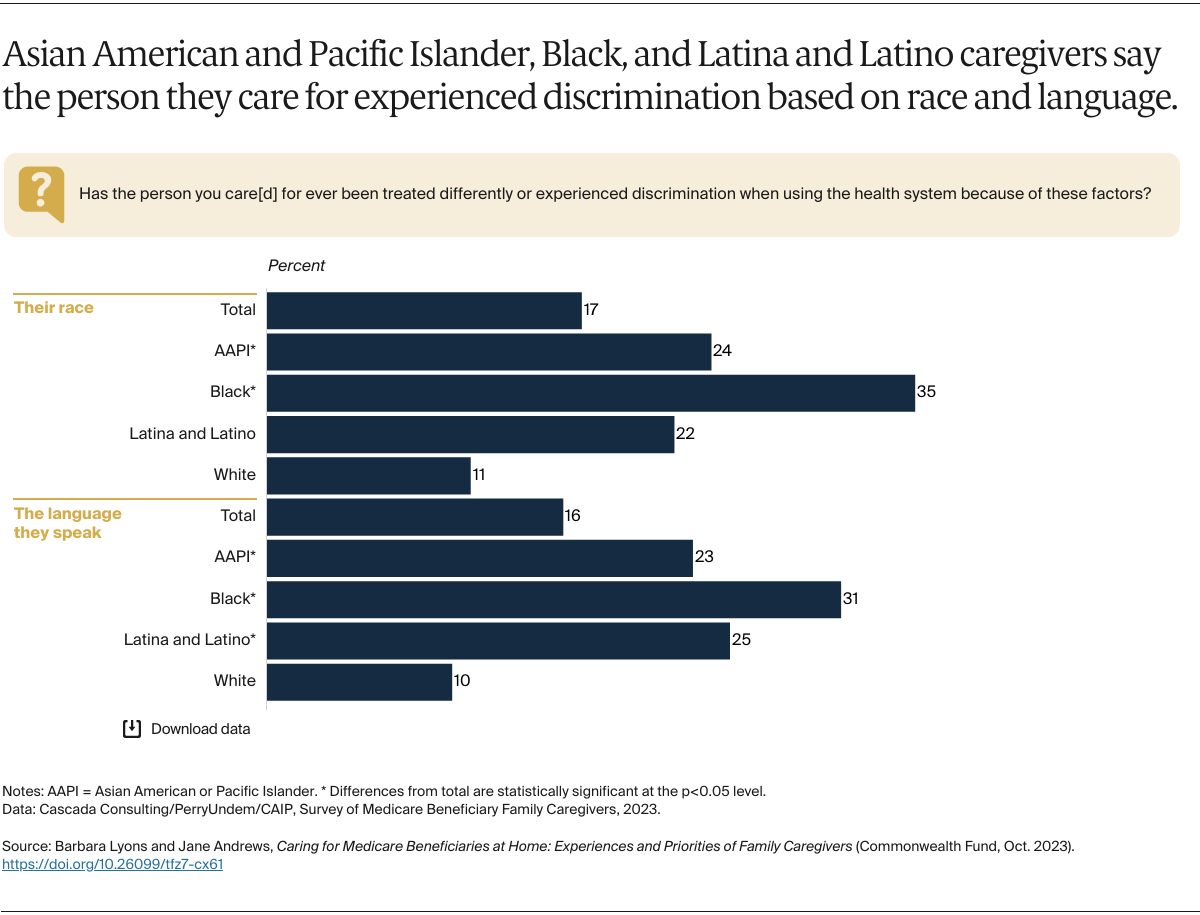

This data brief draws on six focus groups and a national survey of 1,000 family caregivers of Medicare beneficiaries, all conducted in February and March 2023, to understand caregiver experiences and needs, particularly in relation to Medicare. Those surveyed included unpaid adult family or community members who are either currently assisting a Medicare beneficiary with home health, personal care, or household management tasks or have done so in the past four years. We engaged with a diverse sample of family caregivers across genders, age, race, geography, and ethnicity (see “How We Conducted This Study” for more details).

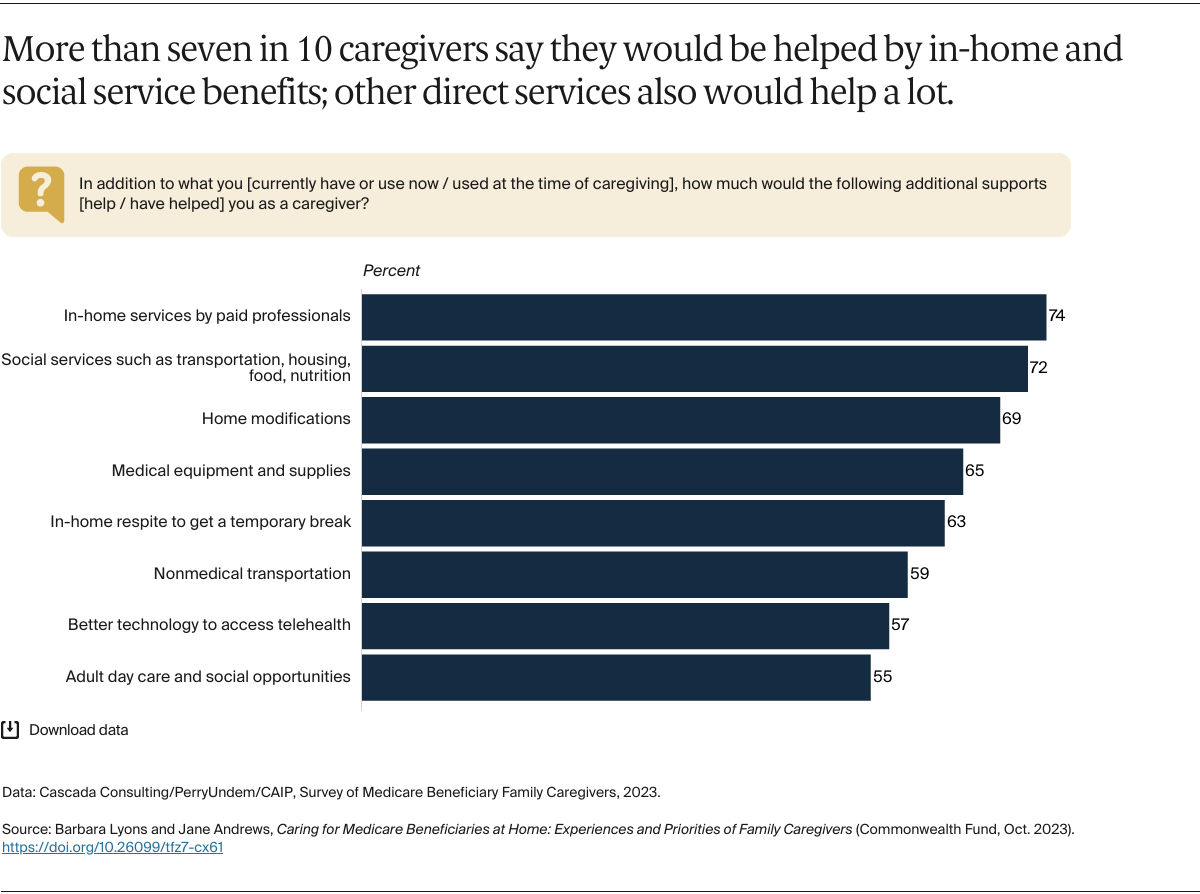

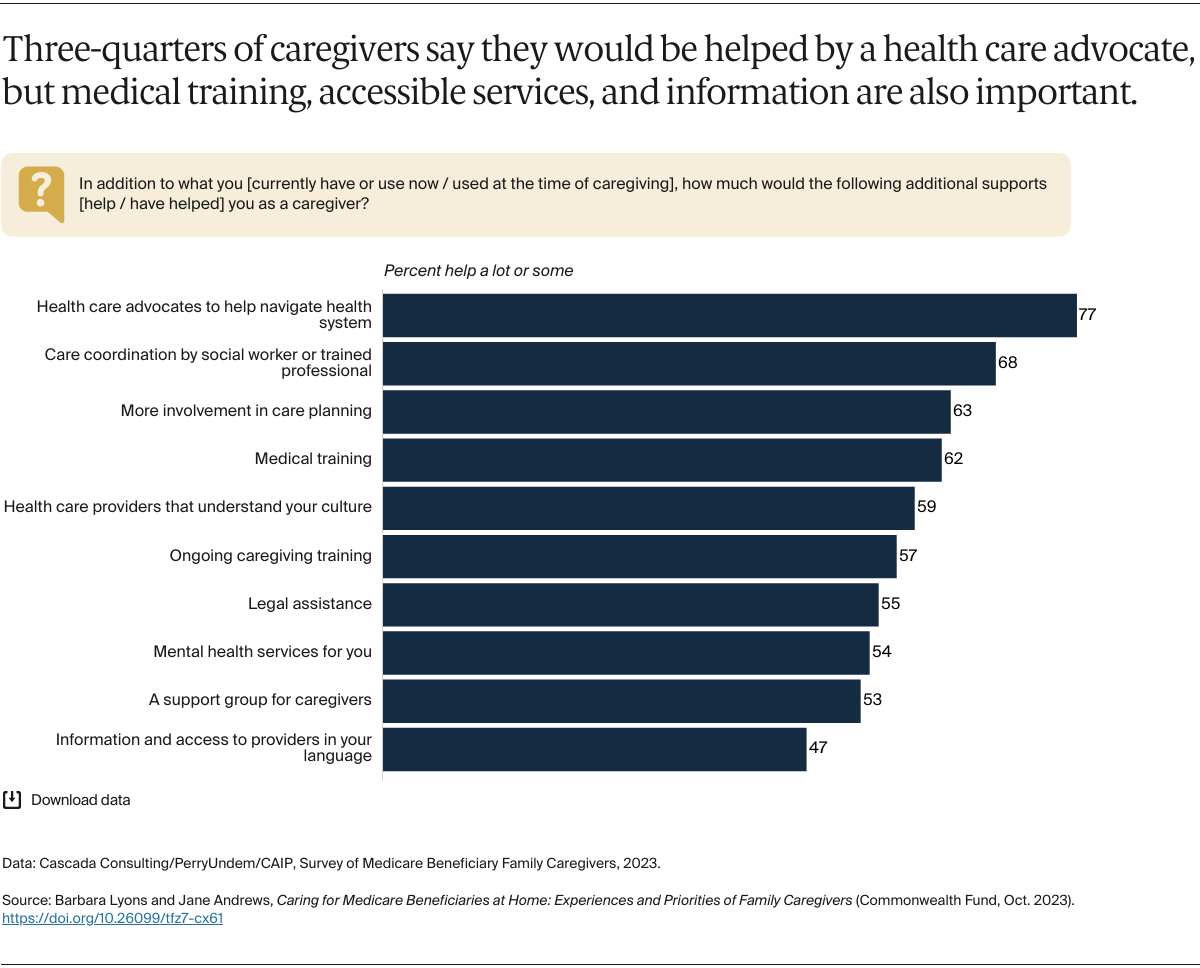

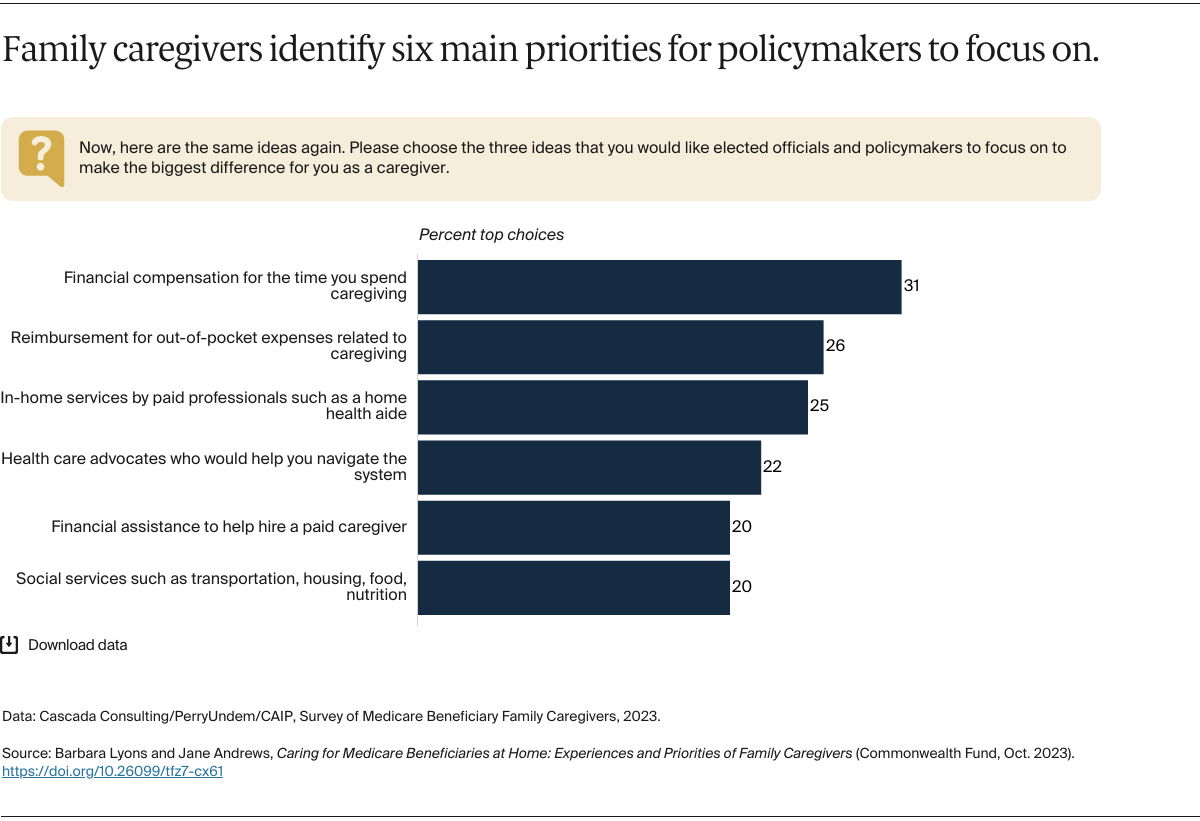

In a companion brief, we offer an array of policy options for better supporting family caregivers and improving care for Medicare beneficiaries at home.3 These include policies to increase Medicare coverage of in-home services and financial support for family caregivers, as well as efforts to expand access to navigational support for families.