Abstract

- Issue: Enrollment in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces is at an all-time high, and sign-ups are expected to increase as Medicaid redeterminations resume. These gains, alongside a more stable legal and political environment relative to the ACA’s early years, may provide opportunities for marketplaces to pursue innovative and consumer-friendly policies that bolster this crucial source of affordable, comprehensive health insurance.

- Goal: Identify key policy decisions across the ACA marketplaces aimed at improving consumers’ access to and experience shopping for coverage that meets their health and financial needs.

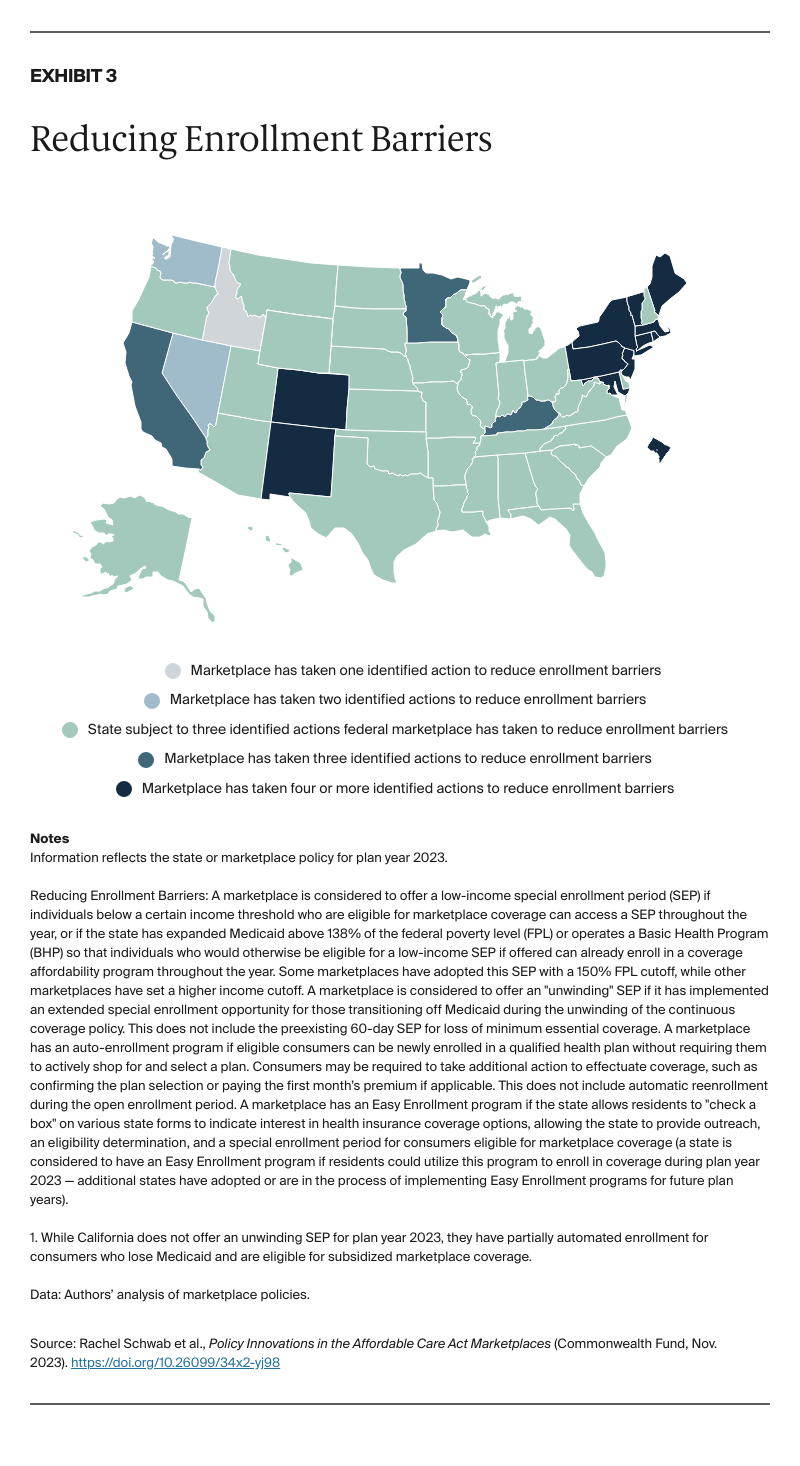

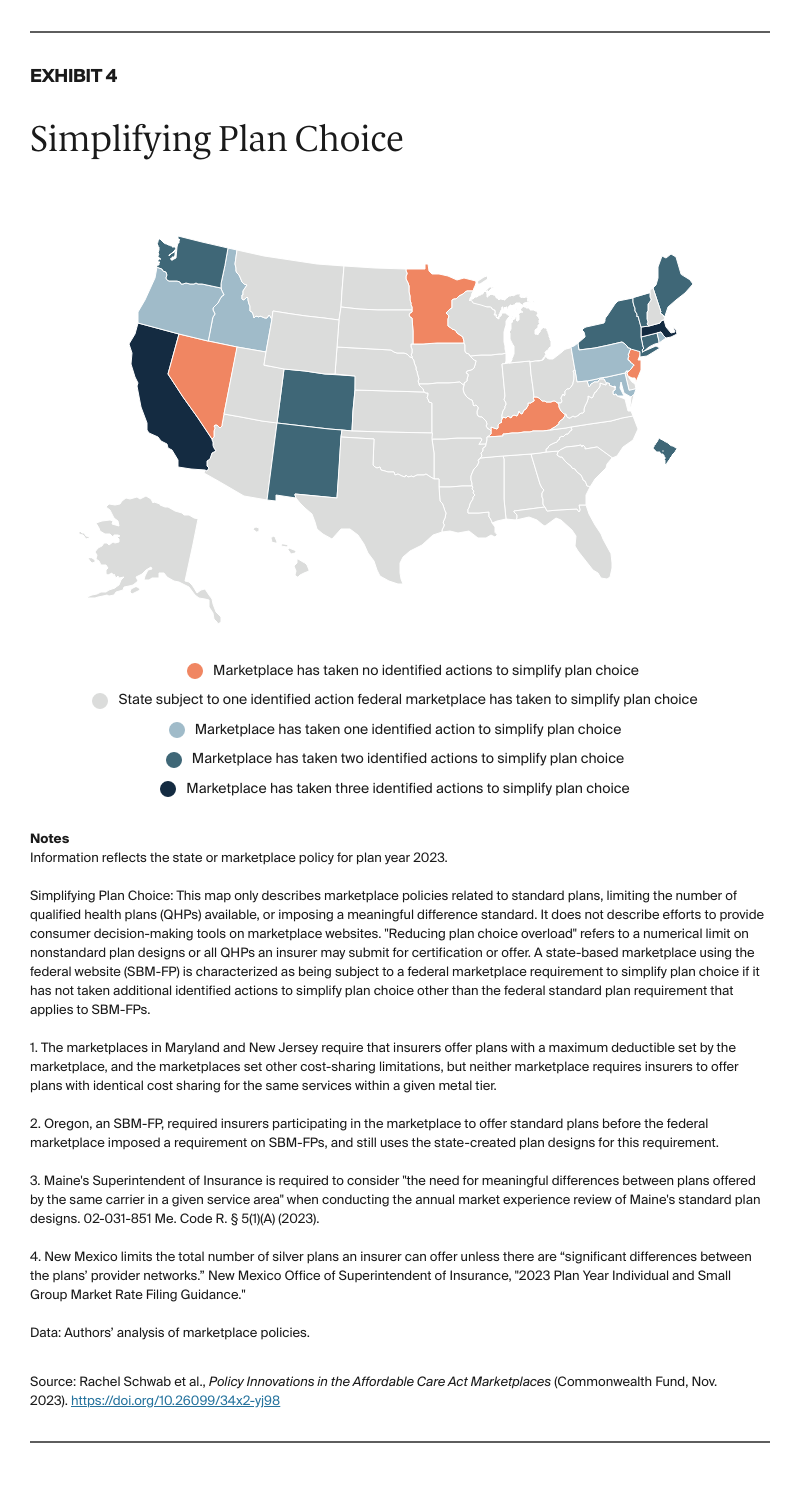

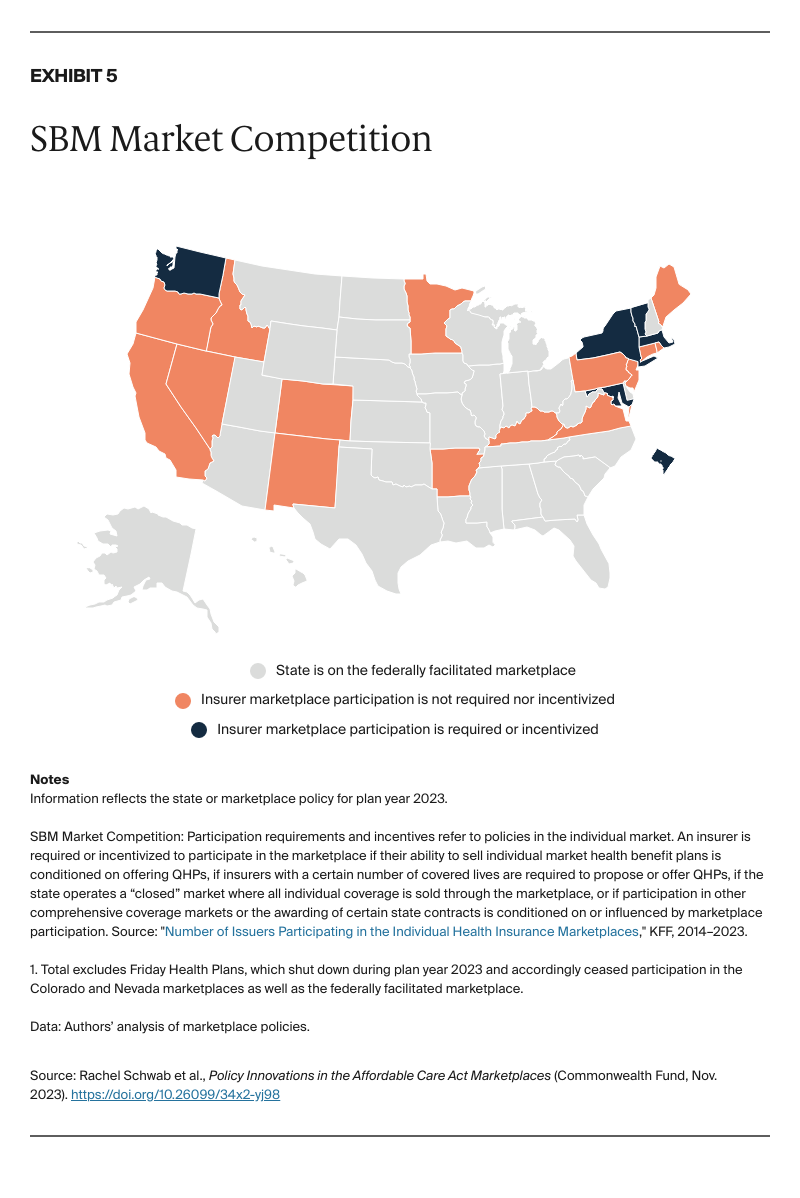

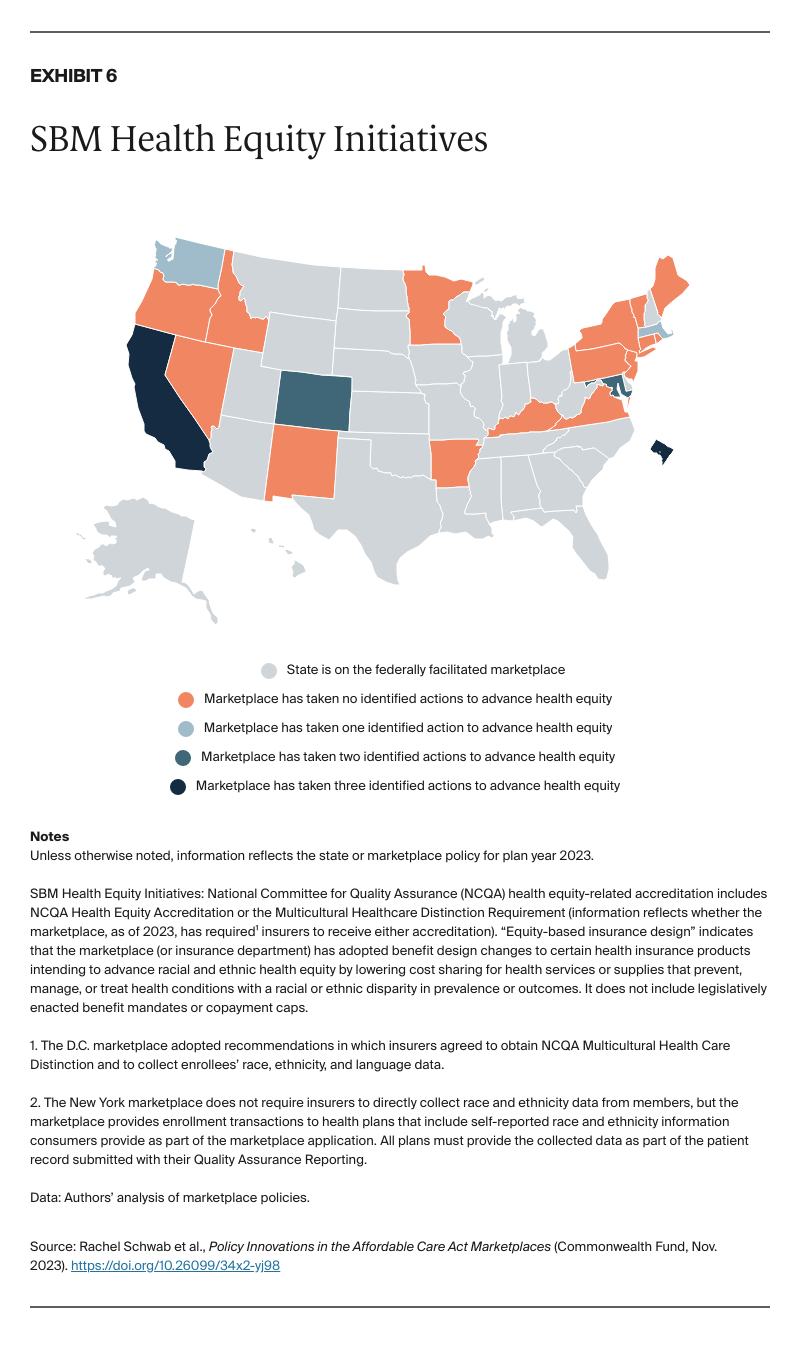

- Methods: We reviewed policy decisions made by the 21 state-run marketplaces and the federally facilitated marketplace for 2023, including efforts to reduce enrollment barriers, simplify plan choice, promote market competition, and increase health equity.

- Key Findings: Marketplaces have adopted policies designed to connect consumers to coverage by reducing administrative burdens, helping consumers navigate their plan options, requiring or incentivizing insurer participation, and taking steps to reduce health and coverage disparities.

- Conclusion: Marketplace policy innovations have helped strengthen a crucial part of the safety net. However, some policies that hold promise for improving coverage access have yet to be adopted broadly, and wide variation across states suggests a need for nationwide implementation of some of the policies identified.

Introduction

More people than ever rely on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces for health insurance.1 Millions more will become eligible for marketplace coverage after losing Medicaid as the pandemic-related pause on redeterminations comes to an end.2 Amidst this flurry of enrollment activity, policymakers running the ACA marketplaces shoulder the great responsibility of connecting consumers to affordable coverage that meets their health and financial needs. After years of attempts to overturn the ACA in Congress and at the Supreme Court, the marketplaces, now in a relatively stable political and legal environment, may have an increased opportunity to pursue innovative and consumer-friendly policies.

How the ACA Marketplaces Transformed Individual Insurance

While most Americans are insured through their employers or public programs, such as Medicare or Medicaid, more than 18 million people depend on the private individual health insurance market for coverage.3

The ACA transformed this insurance market. Before the ACA, people purchasing insurance on the individual market faced significant barriers to comprehensive and affordable coverage. Insurers competed through discriminatory policies, benefit designs, and pricing schemes, frequently denying insurance applications, creating products designed to cherry-pick healthy individuals, or offering only paltry or unaffordable coverage to people with preexisting conditions.4 Consumers lacked a neutral, centralized source of information about insurance products, making it difficult to compare plans.5

The ACA outlawed these discriminatory practices in the individual market and created “marketplaces,” a one-stop shopping experience on a trusted government website to enroll in federally subsidized health insurance plans that meet a common set of coverage standards. Marketplaces were meant to foster competition on price and value, facilitate meaningful plan comparison, and allow consumers to enroll in affordable, comprehensive private coverage.6

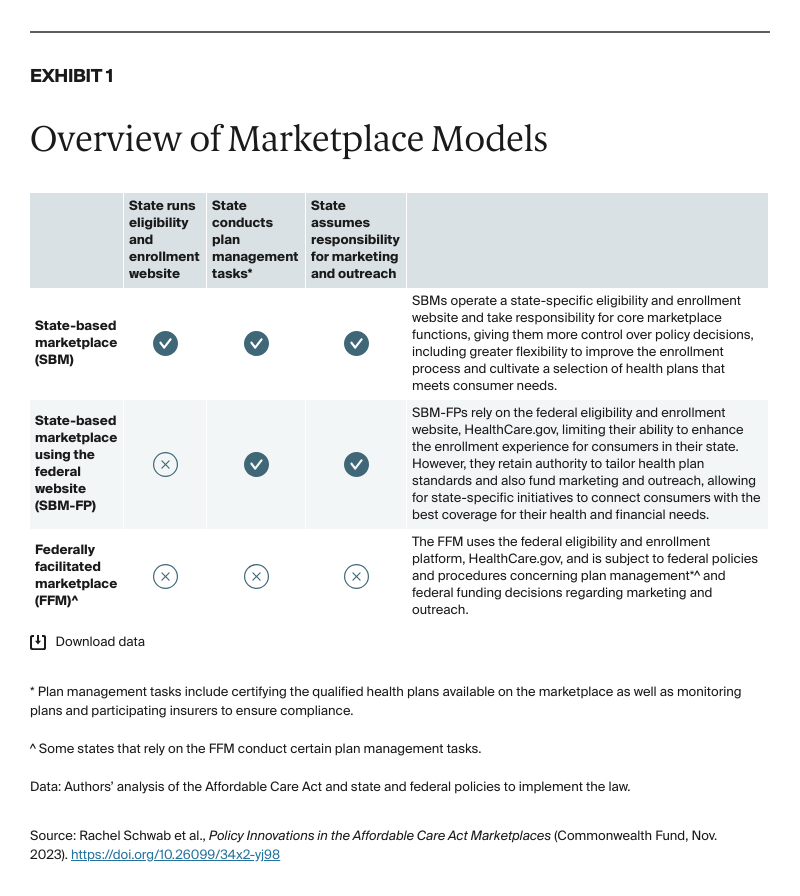

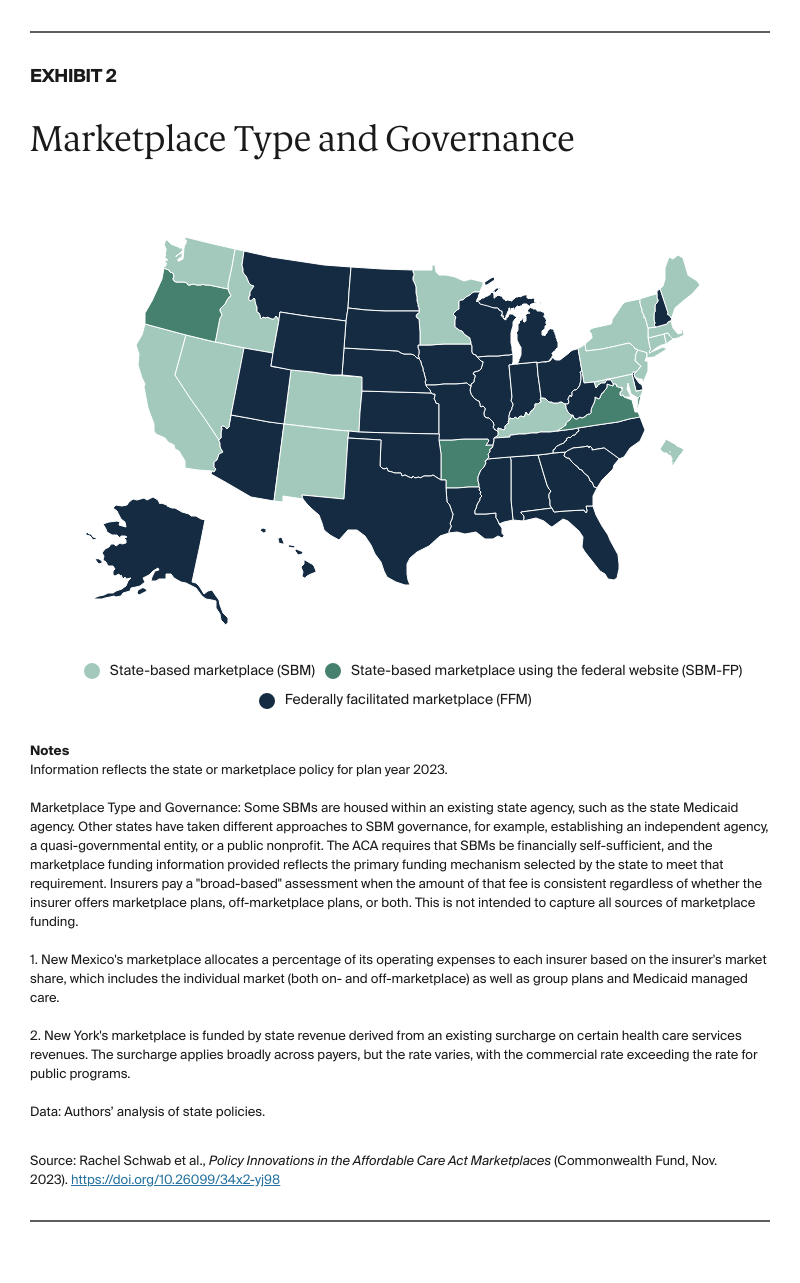

Marketplaces were originally envisioned as a state-operated mechanism. However, in part because of opposition to the ACA, most states initially ceded responsibility for running their marketplace — and with it, the opportunity to use these platforms to drive state innovation — to the federal government.7 In 2023, 20 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) operate a state-based marketplace using a state-run eligibility and enrollment website (SBM) or a state-based marketplace using the federal eligibility and enrollment website, HealthCare.gov (SBM-FP). The remaining 30 states rely on the federally facilitated marketplace (FFM) (Exhibits 1 and 2).

When the marketplaces launched in 2013, website failures and political opposition to the ACA hindered enrollment efforts.8 After some progress in the first couple of years, enrollment dipped again between 2017 and 2020 amidst federal policies that undermined the marketplaces, lackluster insurer participation, and significant premium increases.9 But following congressional action to expand federal premium subsidies, and under the stewardship of a more supportive administration, marketplace enrollment rebounded, with a record 16.4 million people selecting a marketplace plan in 2023 — more than double the enrollment seen in the inaugural sign-up period.10