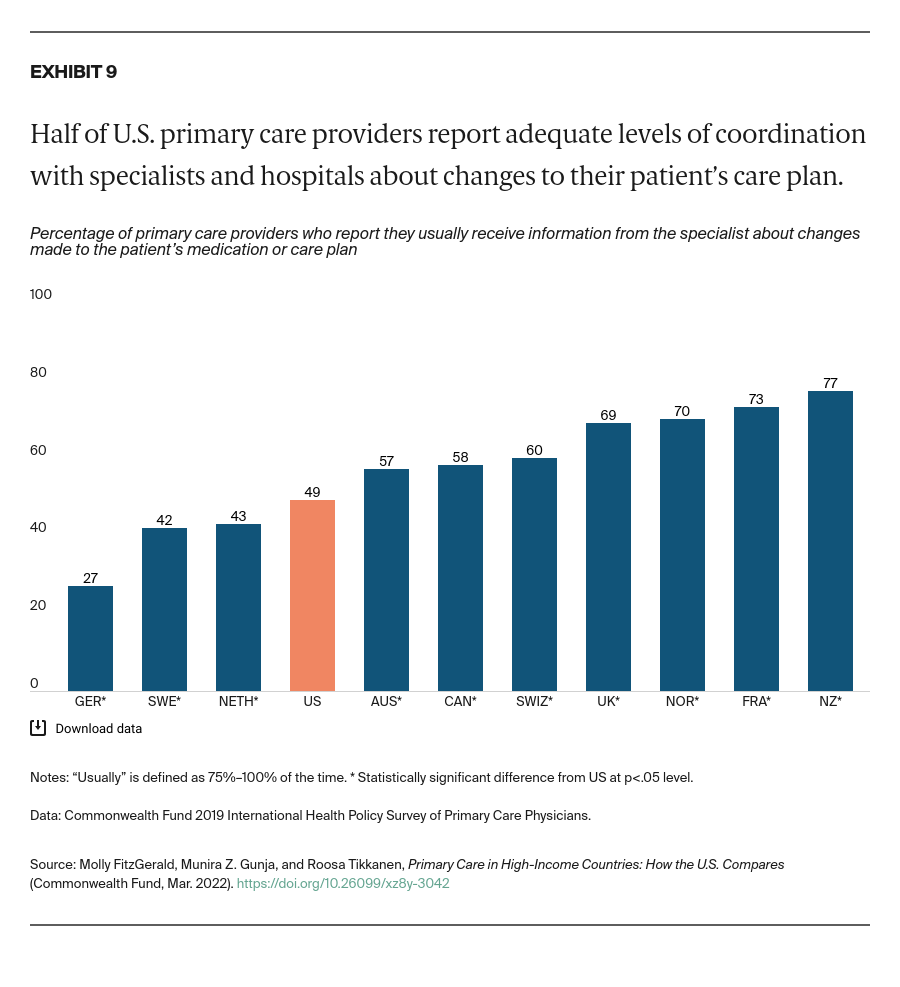

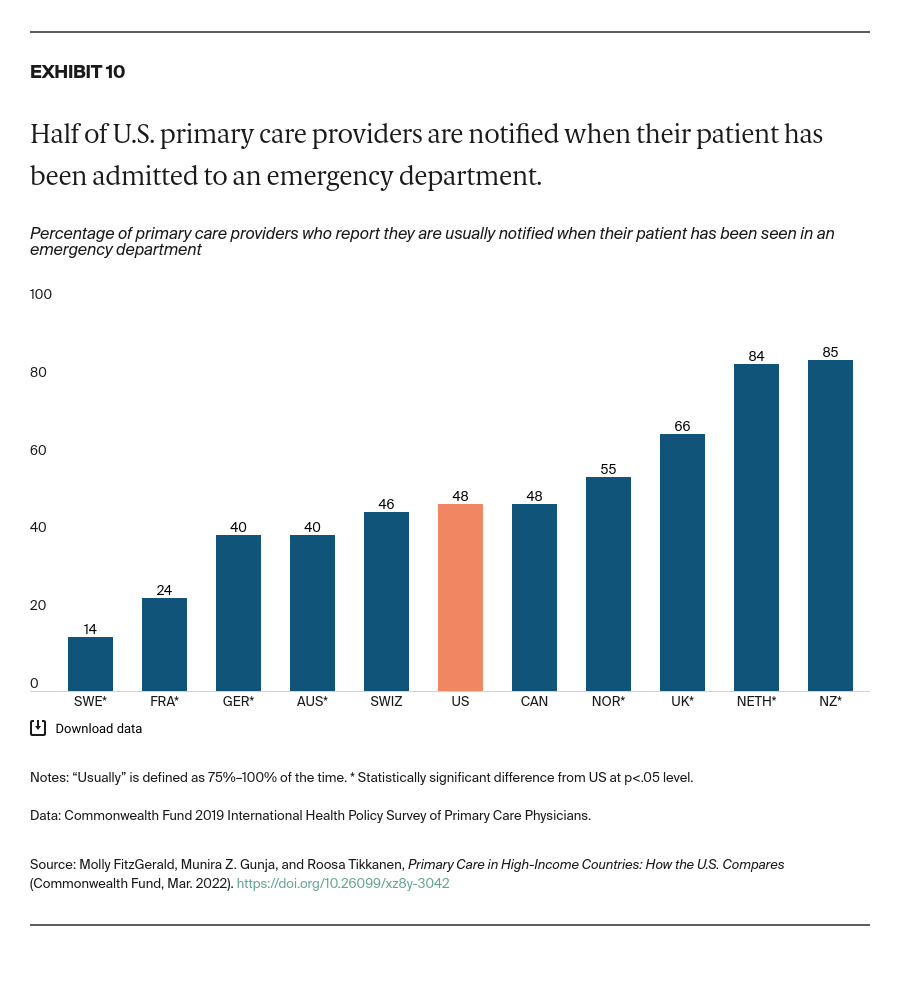

Less than half of U.S. PCPs reported that they are usually informed when another provider changes their patient’s care plan or medication regimen, and that they are usually informed if their patient is admitted to a hospital or emergency department. That’s about the average for the 11 countries we studied. PCPs from New Zealand were the most likely to usually receive this information from specialists and hospitals.

Commonwealth Fund researchers have found that a substantial proportion of U.S. PCPs do not routinely receive timely notification when their patients are seen by other providers, nor do they routinely receive important information resulting from these visits.19

Discussion

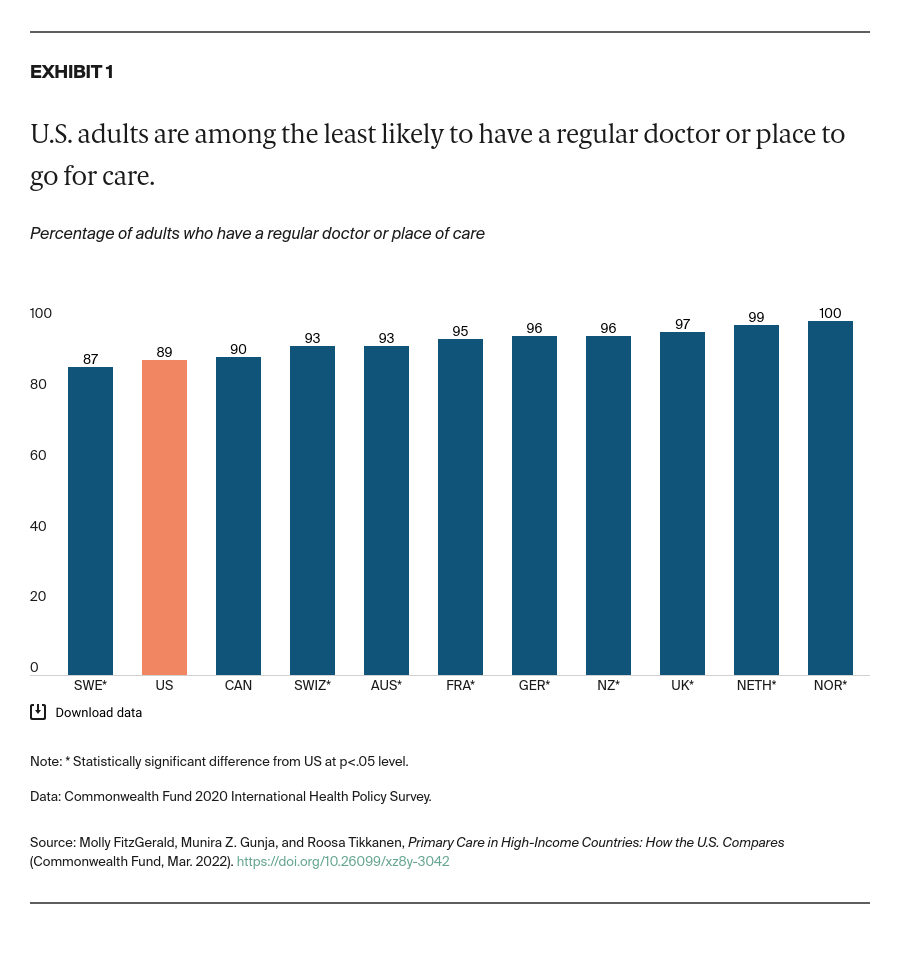

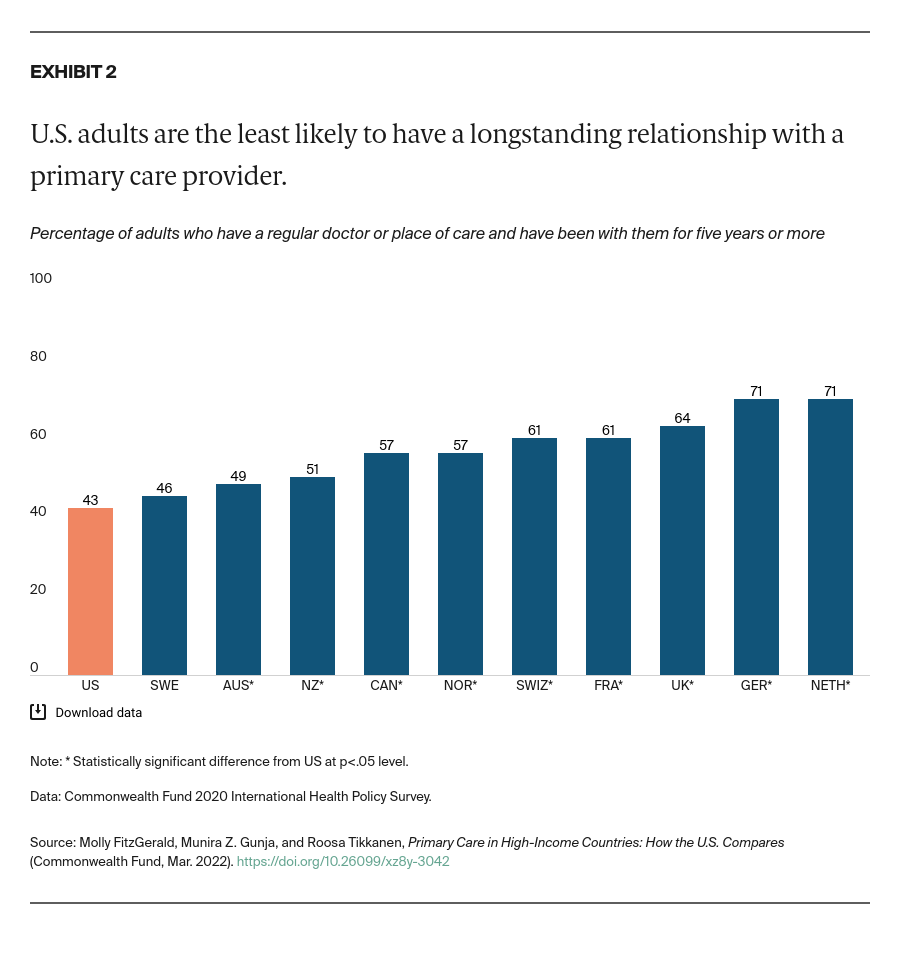

While there is a shortage of health workers globally, our analysis demonstrates that the U.S. primary care system trails far behind those of other countries in many areas, particularly when it comes to health care access and continuity. These findings are consistent with prior research on the challenges facing primary care more broadly and are likely an outcome of chronic underinvestment in primary care in the United States.20 Evidence suggests that the shortcomings of U.S. primary care disproportionately affect predominantly Black and Latinx communities and rural areas, exacerbating disparities that have widened during the COVID-19 pandemic.21

There are several policy options for U.S. policymakers to consider as they work to improve primary care:

Narrow the U.S. wage gap between generalist and specialist physicians and subsidize medical school tuition fees to incentivize medical students to opt for primary care practice. The United States has the largest wage gap and highest tuition fees among the countries we studied.22

Invest in telehealth to allow more patients to access primary care. This is particularly important for rural residents and people with low income, who face some of the tallest barriers to getting care.23 Only one in five U.S. PCPs reported that their practice provided video consultations before the COVID-19 pandemic, and just over a third of U.S. patients with a regular doctor or place of care said they have used a secure website or patient portal to communicate with their provider within the past two years (data not shown).24

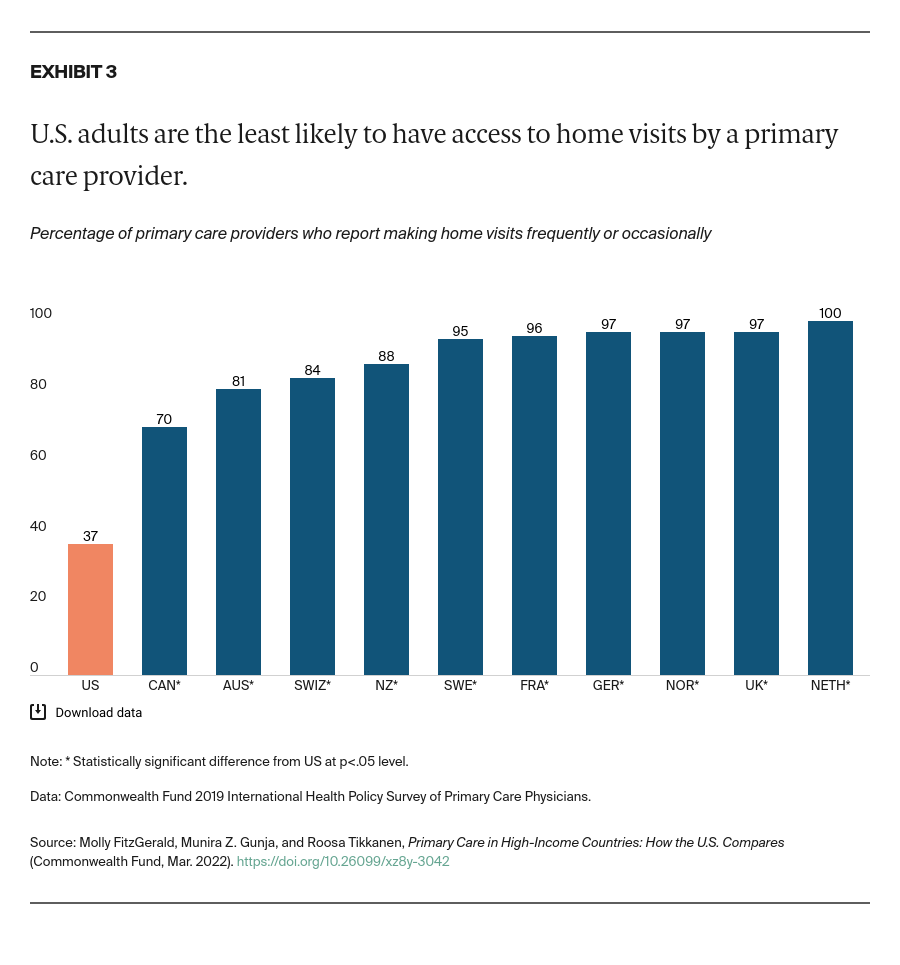

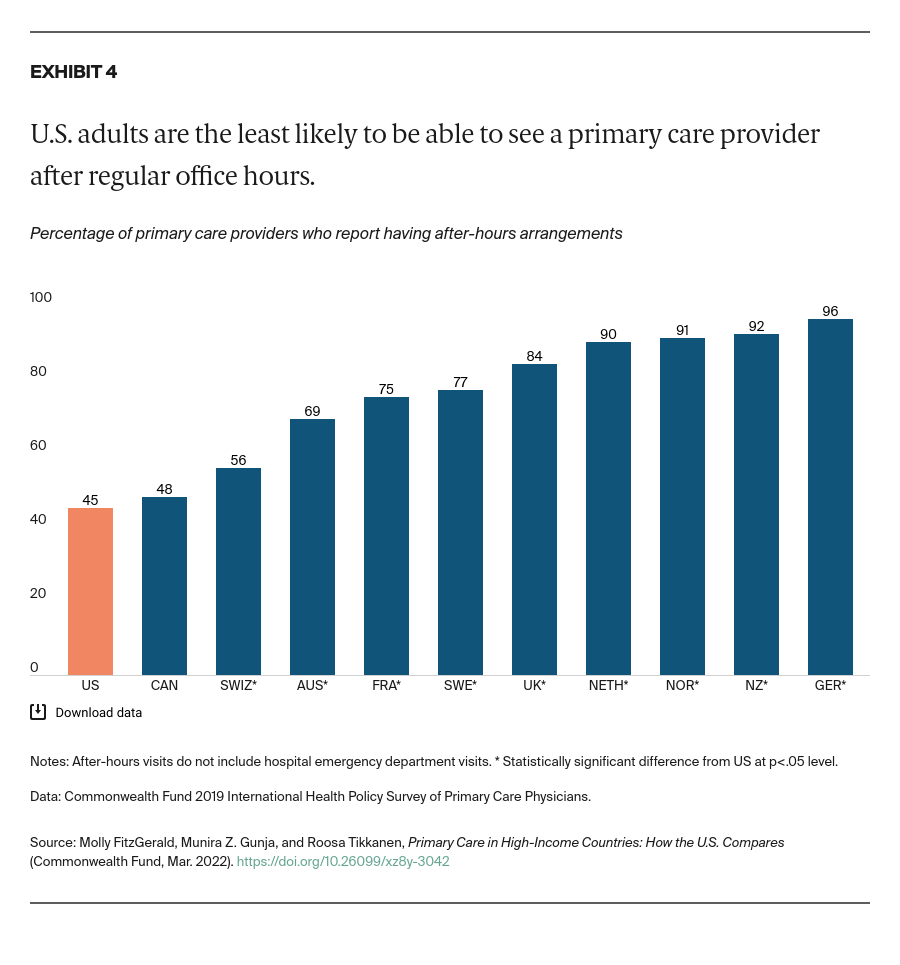

Expand payment reforms that reward and hold providers accountable for the continuity of care. Countries with top-performing health systems are able to reduce avoidable mortality through investment in primary care models that ensure continuity of care.25 Ensuring that patients can receive care after-hours, and get treatment in their own homes, is critical to avoiding unnecessary trips to the emergency department. There has been some recent progress in this area: Medicare eliminated the requirement for providers to provide documentation that a home visit, instead of an office visit, is medically necessary.26 By removing this administrative hurdle, this change should allow physicians to care for patients more easily in their homes and reduce fragmentation of care.

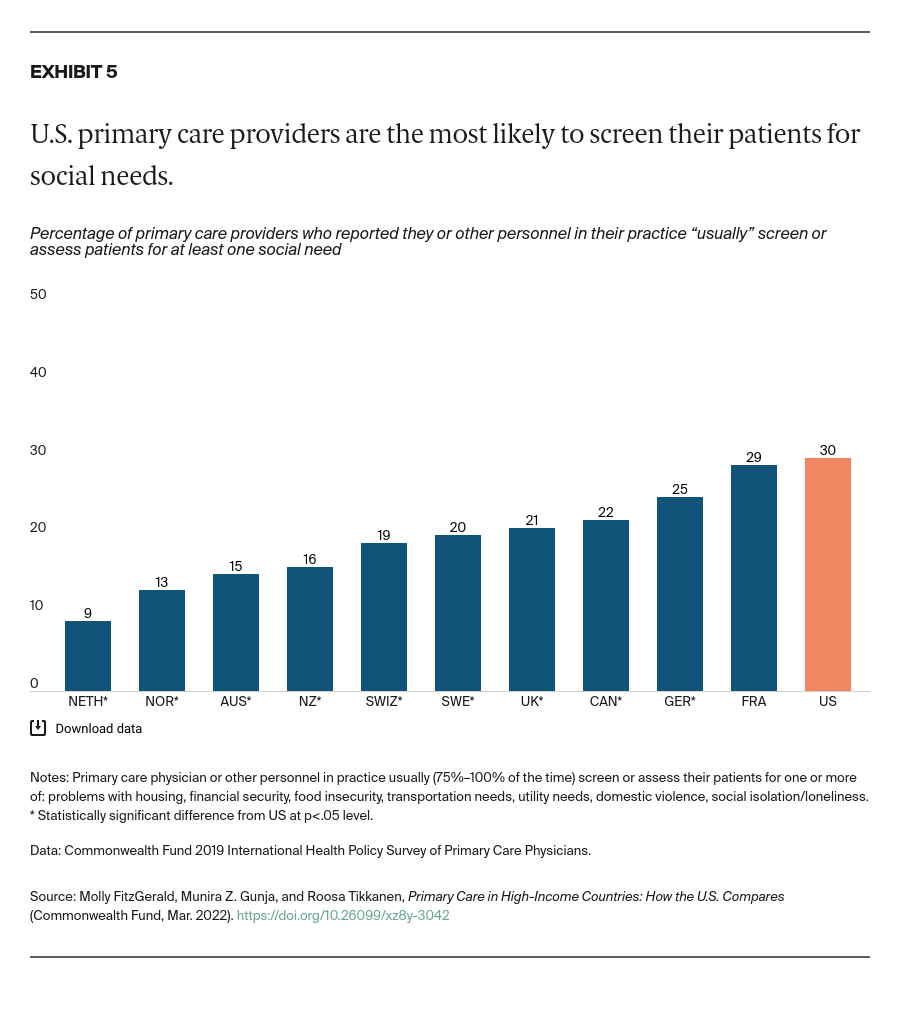

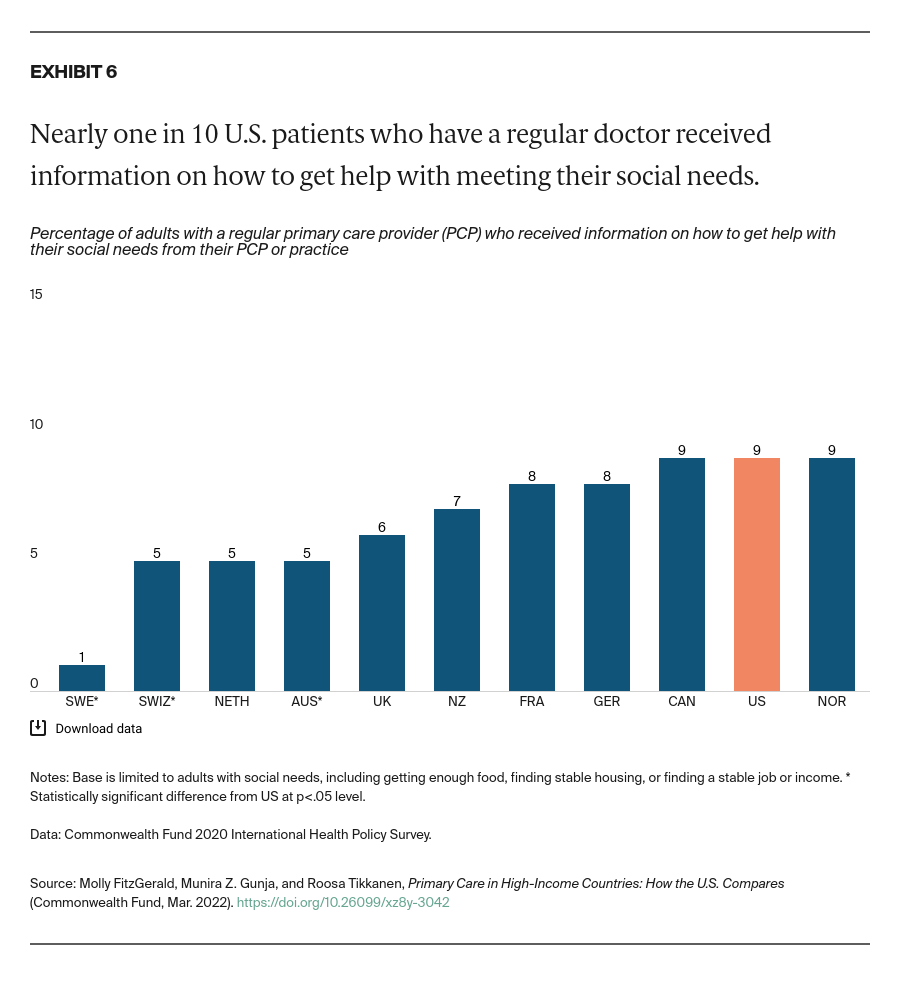

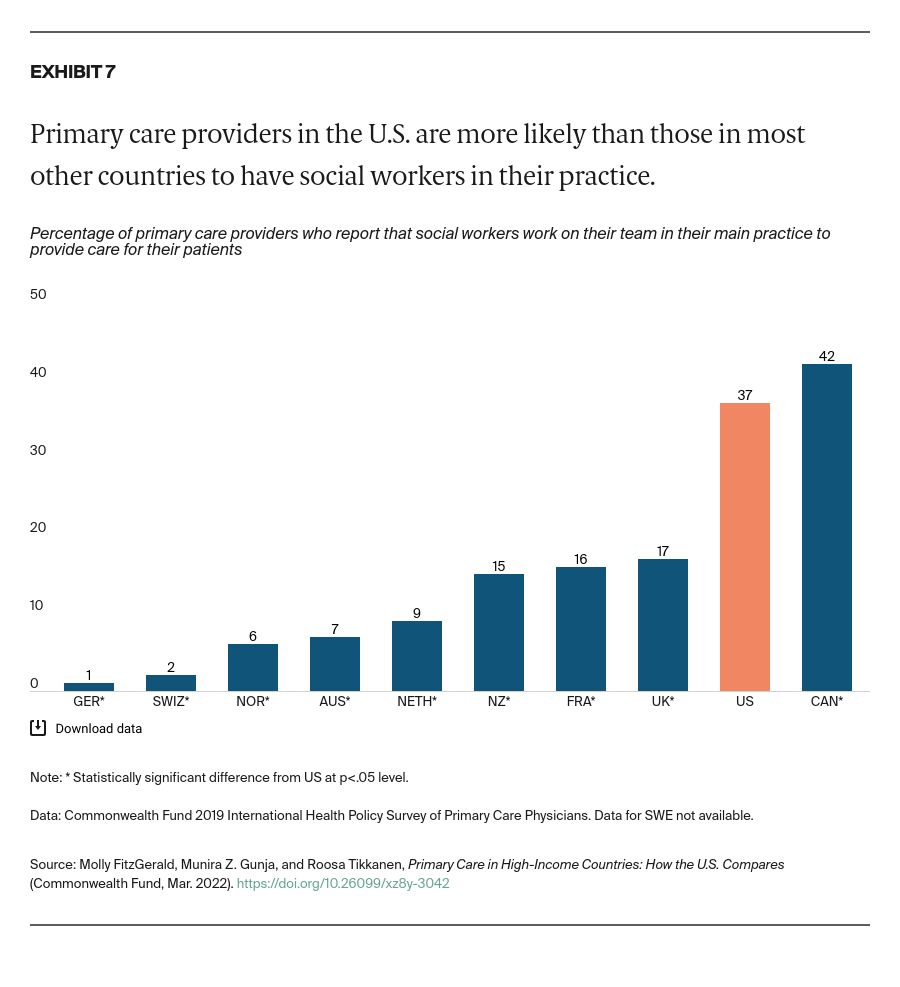

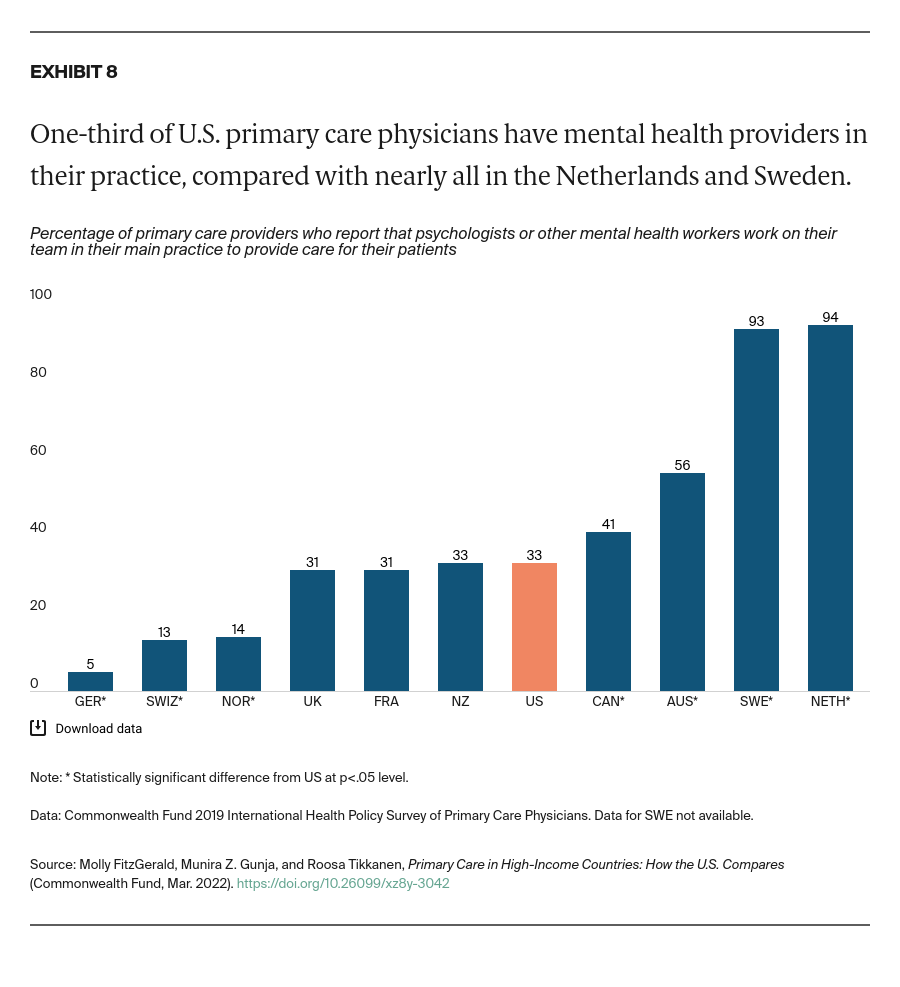

Acknowledge the importance of meeting social service needs to people’s health and well-being. Social determinants of health account for as much as 55 percent of health outcomes.27 While U.S. primary care appears to be somewhat more comprehensive in terms of screening for social needs, our analysis also finds that U.S. adults are more likely to worry about their social needs in the first place — especially compared to adults in Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden.28

Create financial incentives to facilitate communication between patients’ providers. The fragmentation in care between U.S. PCPs and specialists can have a negative impact on care quality, cost, and outcomes.29 In New Zealand, primary health organizations received additional per capita funding to promote health and coordinate care.30 Introducing similar incentives in the U.S. could help.

In its efforts to improve primary care, the United States can learn a lot from what other high-income countries are doing. But there are also ample lessons to be learned from lower-income countries, such as Costa Rica, whose health system is anchored by robust, community-oriented primary health care.31 And, in the era of COVID-19, a greater understanding of changes and challenges to primary care, particularly from the perspective of the physician, is needed. To that end, the Commonwealth Fund will release findings from its latest international survey, focusing on primary care physicians, in summer 2022.